BENEDICT BISCOP and CUTHBERT

TWO IMPORTANT ABSENTEES FROM

THE SYNOD OF WHITBY

INTRODUCTION:

he

Synod of Whitby in 664 AD was the great pivotal event of

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. At

this synod King Oswy made the key decision that in

future his kingdom was to align its churchmanship with

that of the Rome, rather than the tradition of the

Irish-Celtic church, which had restored Northumbria to

the Christian faith.

he

Synod of Whitby in 664 AD was the great pivotal event of

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. At

this synod King Oswy made the key decision that in

future his kingdom was to align its churchmanship with

that of the Rome, rather than the tradition of the

Irish-Celtic church, which had restored Northumbria to

the Christian faith.

The

debate at the Synod of Whitby is recounted in some

detail by Bede, and by Eddius Stephanus in his Life of

Wilfrid. The dramatis personae of key figures is set out

in detail. They include Wilfrid, Agilbert, Cedd, Hilda

and Colman of Lindisfarne. There are two striking

absentees from this cast list: Cuthbert and Benedict

Biscop.

THE IMPORTANT ABSENCE

rom a later

historic perspective the twin absence of these key

figures does appear suprising. Both men had growing

reputations, both were on the threshold of their prime

years, both had become strongly identified with the

churchmanship they represented. If you were familiar

with the histories of these two men you would have

expected them to be present at the synod. The reasons we

can discern as to 'Why not?' are instructive. They serve

to explain why the subsequent roles played by these

saints were so effective, so influential and ultimately

so complimentary.

rom a later

historic perspective the twin absence of these key

figures does appear suprising. Both men had growing

reputations, both were on the threshold of their prime

years, both had become strongly identified with the

churchmanship they represented. If you were familiar

with the histories of these two men you would have

expected them to be present at the synod. The reasons we

can discern as to 'Why not?' are instructive. They serve

to explain why the subsequent roles played by these

saints were so effective, so influential and ultimately

so complimentary.

Absence from the synod

may even have proved helpful to both Biscop and

Cuthbert. They were not affected by, or implicated in,

the rather bruising exchanges which Bede describes. They

were to come to new roles in the church with a 'clean

sheet',enabling new beginnings and the healing of

wounds. Both men were to prove significant figures in

the shaping of the Northumbrian church that emerged in

the aftermath.

After Whitby the flow

of the church's progress in Northumbria changed course.

For a time it was to flow in two separate, yet

complimentary channels. I will argue that Cuthbert and

Biscop were the two most influential personalities in

the shaping of this twin flow, and in inspiring the

subsequent intermingling of the waters.

THE ROLES OF BISCOP AND CUTHBERT AFTER THE SYNOD

fter the synod,

Cuthbert was required to undertake a new role on

Lindisfarne. This tidal island had been the very heart

of the Irish-Celtic tradition, and the site of the first

monastery and school founded by Aidan and his community

of monks from Iona. From

this island Aidan and his

monks had radiated into Northumbria, preaching, teaching

and in time founding daughter monastries to underpin the

work. The Whitby ruling, and the subsequent departure of Bishop Colman with many monks,

found Lindisfarne depleted and somewhat demoralised.

Cuthbert was to revive and redirect the spirituality and

purpose of the community. In doing so he created a

template for other Irish-Celtic foundations, such as

Melrose and Whitby, which had now to accept the new

dispensation.

fter the synod,

Cuthbert was required to undertake a new role on

Lindisfarne. This tidal island had been the very heart

of the Irish-Celtic tradition, and the site of the first

monastery and school founded by Aidan and his community

of monks from Iona. From

this island Aidan and his

monks had radiated into Northumbria, preaching, teaching

and in time founding daughter monastries to underpin the

work. The Whitby ruling, and the subsequent departure of Bishop Colman with many monks,

found Lindisfarne depleted and somewhat demoralised.

Cuthbert was to revive and redirect the spirituality and

purpose of the community. In doing so he created a

template for other Irish-Celtic foundations, such as

Melrose and Whitby, which had now to accept the new

dispensation.

Biscop was part of a

wave of new young enthusiasts for the the Roman

tradition. The decision at Whitby liberated them to

found new monasteries on the continental pattern. They

built in stone and glass, importing Gaulish craftsmen to

enable the work. They established a new style of

cenobitic monasticism, with a strong Benedictine

influence. The great twin monastery of Wearmouth/Jarrow

which Biscop founded was to become a powerhouse of

spirituality, Biblical scholarship and book production.

It became home to the Venerable Bede.

These two new and

complimentary currents in the Northumbrian church were

ultimately to come together in ways that were to be the

inspiration and outworking of the spiritual and cultural

achievement which became known as the Golden Age of

Northumbria.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE DECISION AT WHITBY

efore looking at

the lives of these important saints in more detail, we

must remind ourselves of the significance and impact of

the decision at Whitby. Bede's Ecclesiastical

History embraces three great themes: the coming of

the Christian faith to the British Isles: the rise of

the Kingdom of Northumbria: the forging of the English

Nation. All come together at Whitby. Bede in effect

describes the coming of faith to Britain as a series of

waves, which surge inland but then withdraw. The

adoption of the Roman tradition at Whitby is the final

wave: the one that remains in place throughout our

subsequent history. Whitby also represents a high point

in Northumbrian influence. It ushers in the so-called

Golden Age of Northumbria, with its great cultural,

spiritual and intellectual achievements. The decision at

Whitby is also influential throughout the British Isles

because of the pre-eminence of Northumbria among the

other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the day. It puts in place

a key component of our emerging national character, and

serves to re-align us with the mainstream church. These

continental structures were eventually to evolve into

what was to become known for a time as Christendom.

efore looking at

the lives of these important saints in more detail, we

must remind ourselves of the significance and impact of

the decision at Whitby. Bede's Ecclesiastical

History embraces three great themes: the coming of

the Christian faith to the British Isles: the rise of

the Kingdom of Northumbria: the forging of the English

Nation. All come together at Whitby. Bede in effect

describes the coming of faith to Britain as a series of

waves, which surge inland but then withdraw. The

adoption of the Roman tradition at Whitby is the final

wave: the one that remains in place throughout our

subsequent history. Whitby also represents a high point

in Northumbrian influence. It ushers in the so-called

Golden Age of Northumbria, with its great cultural,

spiritual and intellectual achievements. The decision at

Whitby is also influential throughout the British Isles

because of the pre-eminence of Northumbria among the

other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the day. It puts in place

a key component of our emerging national character, and

serves to re-align us with the mainstream church. These

continental structures were eventually to evolve into

what was to become known for a time as Christendom.

Many of these outcomes

would not have developed in the way that they did, or to

the extent that they did, had it not been for the key

contributions of Cuthbert and Biscop. These subsequent

ministries seemed to progress in their separate but

parallel fields. Eventually there was to be a coming

together which enriched the church and the nation, and

had a major impact both in Britain and on the continent.

The roles that Cuthbert and Biscop came to occupy is

rooted in their years of Christian formation and the

very different paths they followed in their early lives.

The life of Cuthbert is fairly well-known and has been

widely documented. Biscop is a more shadowy figure and

most who encounter him feel that his life deserves

greater celebration.

CUTHBERT'S EARLY LIFE

e first encounter

Cuthbert in the Lammermuir hills, in what is now the

border country of Scotland. He seems to be of

British-Celtic stock. The fact that he owned a horse, on

which he travelled widely, would suggest that he was of

a noble family. One or two prophetic episodes illuminate

his childhood and it is clear that he is already

thinking on religious lines about his future.

A formative episode occurs one night

when he is watching sheep with his companions. (Wolves and other predators still abounded in

the Northumbrian countryside). Cuthbert is

already demonstrating his spiritual bent, as he is awake

and praising God. He has a vision of angels. He wakens

his companions. They witness a flight of angels carrying

a 'globe of fire', and realise that they are seeing the

soul of a great man being taken heavenward. Later

enquiry at the nearby monastery of Melrose reveals that

Aidan of Lindisfarne has died, at the very hour of the

shepherd's vision.

e first encounter

Cuthbert in the Lammermuir hills, in what is now the

border country of Scotland. He seems to be of

British-Celtic stock. The fact that he owned a horse, on

which he travelled widely, would suggest that he was of

a noble family. One or two prophetic episodes illuminate

his childhood and it is clear that he is already

thinking on religious lines about his future.

A formative episode occurs one night

when he is watching sheep with his companions. (Wolves and other predators still abounded in

the Northumbrian countryside). Cuthbert is

already demonstrating his spiritual bent, as he is awake

and praising God. He has a vision of angels. He wakens

his companions. They witness a flight of angels carrying

a 'globe of fire', and realise that they are seeing the

soul of a great man being taken heavenward. Later

enquiry at the nearby monastery of Melrose reveals that

Aidan of Lindisfarne has died, at the very hour of the

shepherd's vision.

This experience

confirms Cuthbert's calling and he enters monastic life

at Melrose. The choice of Melrose will be guided no

doubt by its proximity, but Bede also tells us that

Cuthbert is attracted by the reputation of Boisil as a

teacher. Boisil is Prior of Melrose under Abbot Eata.

Boisil is at the gate of the monastery when Cuthbert

arrives and he prophesies a great future for the young

novice. During his

formative years at Melrose, Cuthbert reveals a zeal for

spiritual discipline and a passion for taking the gospel

to the most remote locations that is quite remarkable.

Cuthbert soon is recognised as a man of exceptional

spirituality. He begins to display gifts of prophesy and

healing. When

Abbot Eata is invited to establish another monastery at

Ripon he takes Cuthbert with him and appoints him as

guest master. This initiative founders. (The

reasons for this are instructive and will be examined

later.) Upon their return to Melrose they learn

that Boisil, Cuthbert's beloved teacher is dying. Upon

his passing Cuthbert is appointed Prior. It is clear

that Cuthbert is now widely recognised for his saintly

qualities. His reputation extends beyond the boundaries

of Melrose. He is, for example, invited by the Abbess

Ebbe to pay an encouraging visit to her monastery at

Coldingham.

CUTHBERT AT THE TIME OF WHITBY

o in 664 AD

Cuthbert was a prominent and widely respected figure,

with an important future in the Northumbrian church.

Furthermore his ministry was steeped and rooted in the

Irish-Celtic tradition. His abbot Aeta was a former

pupil of Aidan. Cuthbert had taken that tradition to

even greater levels, and it could be argued that he was

the greatest exemplar of that tradition. His disciplines

were rigorous. His friendships with the domestic animals

which shared his work, and the wild creatures he

encountered, were the finest expression of the

Irish-Celtic alignment with the grain of the natural

world. It would be hard to envisage a more attractive

advocate. Yet Cuthbert was not present at the Whitby

Synod. His three biographies do not record a presence,

and his name does not appear on the list of delegates.

o in 664 AD

Cuthbert was a prominent and widely respected figure,

with an important future in the Northumbrian church.

Furthermore his ministry was steeped and rooted in the

Irish-Celtic tradition. His abbot Aeta was a former

pupil of Aidan. Cuthbert had taken that tradition to

even greater levels, and it could be argued that he was

the greatest exemplar of that tradition. His disciplines

were rigorous. His friendships with the domestic animals

which shared his work, and the wild creatures he

encountered, were the finest expression of the

Irish-Celtic alignment with the grain of the natural

world. It would be hard to envisage a more attractive

advocate. Yet Cuthbert was not present at the Whitby

Synod. His three biographies do not record a presence,

and his name does not appear on the list of delegates.

We can only speculate

as to why Cuthbert, the quintessential Irish-Celtic

saint, was not present at the Synod. The most powerful

and likely reason is the saint's deep humility. At the

heart of this quality lay Cuthbert's profound obedience.

He was not at Whitby because he was not asked to go. A

more ambitious man, sensing the historic nature of the

Synod, may have asked to go or tried to manipulate a

presence. Such characteristics were not part of

Cuthbert's make up. His passion was to be with God and

to do his work. (Many years later, he

was asked to be Bishop of Lindisfarne by the Synod of

Twyford. He resisted all blandishments, even from the

king, until he realised that the unanimous decision of

the Synod meant that this was God's purpose for him.)

He was obedient when asked to take on

responsibility, but had no worldly ambition.

THE EARLY LIFE OF BISCOP BADUCING

iscop was

originally known by the family name of Baducing. He

first emerges into the pages of history in the court of

King Oswy. Here Biscop served the king with some

distinction. His roles may have included military

service. After some years Oswy was poised to give Biscop

a grant of land as a reward for his faithful service. At

that point Bede tells us that Biscop decided to dedicate

his life to Christ. Bede's language is similar to that

used when describing someone about to enter the

religious life. Biscop's purpose is not to join a

monastery however; his great aspiration is to visit

Rome. During his time at court, Biscop had learned of

the great city and its wonderful churches. So he

abandoned the court, and the opportunity of enjoying the

privileged life of a Thane in Anglo- Saxon Northumbria.

iscop was

originally known by the family name of Baducing. He

first emerges into the pages of history in the court of

King Oswy. Here Biscop served the king with some

distinction. His roles may have included military

service. After some years Oswy was poised to give Biscop

a grant of land as a reward for his faithful service. At

that point Bede tells us that Biscop decided to dedicate

his life to Christ. Bede's language is similar to that

used when describing someone about to enter the

religious life. Biscop's purpose is not to join a

monastery however; his great aspiration is to visit

Rome. During his time at court, Biscop had learned of

the great city and its wonderful churches. So he

abandoned the court, and the opportunity of enjoying the

privileged life of a Thane in Anglo- Saxon Northumbria.

Biscop headed south to

Kent in order to cross to the continent, and visited the

court of King Erconbert in Canterbury. Here he met

another potential traveller: none other than the young

Wilfrid. Wilfrid was the protegé of the Northumbrian

Queen. Like Biscop he has

conceived a desire to visit Rome. Erconbert of Kent owed

allegience to Northumbria, and had undertaken that

Wilfrid, who was only eighteen years old, would not be

allowed to travel unless suitable companions could be

found. Biscop aged twenty five, with much more life

experience, was deemed suitable.

Travelling across

Europe in those days was difficult and dangerous. The

journey to Rome could take up to one year. The only

roads were the remnants of the Roman roads, and there

were brigands and wild beasts along the way. The men

progressed well until they reached to town of Lyons.

Here Bishop Annamundus took great interest in the

brilliant and charismatic Wilfrid. He was so taken with

the young man that he wanted to make him his heir.

The lionising of

Wilfrid led to a falling out with Biscop. Wilfrid's head

had clearly been turned by the flattering attention he

was receiving. He wished to remain in Lyons for an

extended period. Biscop

remained firm in his purpose, so there was a parting of

the ways. Biscop went on to Rome, where he may have been

the first Anglo-Saxon freeman to enter the city. (We

recall that blonde blue-eyed Anglo-Saxon slave children

had been seen by Pope Gregory the Great, of whom he

said, when told they were Angles, replied they were

Angels, and when told the name of their king, ‘Alla’,

replied they would sing ‘Allelulia’, and sent St

Augustine as missionary to Canterbury.)

BISCOP IN ROME

n Rome Biscop

stayed at the monastery on the Caelian Hill, founded by

Gregory the Great. From this base he visited the tombs

of Peter and Paul. He was overwhelmed by the

architectural and cultural glories of the city. Most of

the great edifices of empire, such as the Forum, the

Colliseum and

the Circus Maximus remained intact. There were in

addition many churches, and what churches! They were

stone-built with stained-glass windows. The interiors

vibrated with life: frescos, floor-tiles, mosaics,

paintings and icons filled the churches with colour.

Candles and incense added to the sensual richness of the

experience. There was a strong Byzantine influence,

which added to the opulence and mystery of the

spirituality he encountered. Biscop was completely

overwhelmed by the experience. He returned to Britain

totally converted to the merits of the Roman tradition.

He reported his experience with enthusiasm and, armed

with this recent first-hand experience, quickly emerged

as one of the leaders of the pro-Roman group.

n Rome Biscop

stayed at the monastery on the Caelian Hill, founded by

Gregory the Great. From this base he visited the tombs

of Peter and Paul. He was overwhelmed by the

architectural and cultural glories of the city. Most of

the great edifices of empire, such as the Forum, the

Colliseum and

the Circus Maximus remained intact. There were in

addition many churches, and what churches! They were

stone-built with stained-glass windows. The interiors

vibrated with life: frescos, floor-tiles, mosaics,

paintings and icons filled the churches with colour.

Candles and incense added to the sensual richness of the

experience. There was a strong Byzantine influence,

which added to the opulence and mystery of the

spirituality he encountered. Biscop was completely

overwhelmed by the experience. He returned to Britain

totally converted to the merits of the Roman tradition.

He reported his experience with enthusiasm and, armed

with this recent first-hand experience, quickly emerged

as one of the leaders of the pro-Roman group.

BISCOP ON THE CONTINENT

t this point a

strange ten-year gap appears in Biscop's biography, as

recounted by Bede. Most scholars concur that Biscop

probably spent this time touring continental

monasteries. He says of his later foundation, that he

introduced a rule distilled from his experiences in

seventeen continental monasteries. Given the

difficulties of travel, the only sufficient time Biscop

could have devoted to such an extensive tour was during

the 'missing' ten-year period. This absence did mean

that the leadership of the new Roman movement fell into

other hands. Furthermore he was no longer in Britain

when Wilfrid finally returned.

t this point a

strange ten-year gap appears in Biscop's biography, as

recounted by Bede. Most scholars concur that Biscop

probably spent this time touring continental

monasteries. He says of his later foundation, that he

introduced a rule distilled from his experiences in

seventeen continental monasteries. Given the

difficulties of travel, the only sufficient time Biscop

could have devoted to such an extensive tour was during

the 'missing' ten-year period. This absence did mean

that the leadership of the new Roman movement fell into

other hands. Furthermore he was no longer in Britain

when Wilfrid finally returned.

WILFRID'S FURTHER ADVENTURES

ilfrid stayed in

Lyons for a further six months after Biscop's departure

before belatedly setting off to Rome. Here he met

Archdeacon Boniface, who introduced him to the Pope. He

was clearly identified as a young man of promise and he

returned to Lyons filed with new enthusiasm. He took the

tonsure and became a monk in the Roman tradition.

Shortly afterwards Queen Baldhild initiated a

persecution of Christians. Rather than engage in

wholesale slaughter, she elected to execute certain

bishops. Annumundus was arraigned and, after a 'show'

trial, condemned to death. When taken to the place of

execution, Wilfrid, his protegé, insisted on

accompanying him. At the place of execution Wilfrid

stripped off and presented himself to the executioner.

Wilfrid's youth and Anglo-Saxon appearance betrayed him.

Enquiries were made and, when it became clear that the

young man was a recent visitor from Britain, they

refused to execute him with Annamundus. After the death

of his mentor, the authorities put Wilfrid on a boat and

he sailed via Marsailles back to Britain.(Wilfrid's

later ministry is often criticised, but one thing this

episode demonstrates is that he was a very courageous

young man).

ilfrid stayed in

Lyons for a further six months after Biscop's departure

before belatedly setting off to Rome. Here he met

Archdeacon Boniface, who introduced him to the Pope. He

was clearly identified as a young man of promise and he

returned to Lyons filed with new enthusiasm. He took the

tonsure and became a monk in the Roman tradition.

Shortly afterwards Queen Baldhild initiated a

persecution of Christians. Rather than engage in

wholesale slaughter, she elected to execute certain

bishops. Annumundus was arraigned and, after a 'show'

trial, condemned to death. When taken to the place of

execution, Wilfrid, his protegé, insisted on

accompanying him. At the place of execution Wilfrid

stripped off and presented himself to the executioner.

Wilfrid's youth and Anglo-Saxon appearance betrayed him.

Enquiries were made and, when it became clear that the

young man was a recent visitor from Britain, they

refused to execute him with Annamundus. After the death

of his mentor, the authorities put Wilfrid on a boat and

he sailed via Marsailles back to Britain.(Wilfrid's

later ministry is often criticised, but one thing this

episode demonstrates is that he was a very courageous

young man).

WILFRID IN NORTHUMBRIA

pon his return

Wilfrid lost no time in becoming a leading champion of

the Roman tradition. He was taken up by Aldred, the son

of King Oswy, and the sub-king of Deira. There was an

early episode which forshadowed things to come. Having

already invited Aeta to found a new monastery at Ripon.(This was the occasion referred to above when

Cuthbert became the guest master). Aldred then

proceeded to insert Wilfrid into the leadership of the

community. (It is unclear where ultimate

authority was to lie). It quickly

became clear that Wilfrid would brook no compromise

between the two traditions and so, rather than permit

conflict, Aeta, Cuthbert and their companions withdrew

to Melrose.

pon his return

Wilfrid lost no time in becoming a leading champion of

the Roman tradition. He was taken up by Aldred, the son

of King Oswy, and the sub-king of Deira. There was an

early episode which forshadowed things to come. Having

already invited Aeta to found a new monastery at Ripon.(This was the occasion referred to above when

Cuthbert became the guest master). Aldred then

proceeded to insert Wilfrid into the leadership of the

community. (It is unclear where ultimate

authority was to lie). It quickly

became clear that Wilfrid would brook no compromise

between the two traditions and so, rather than permit

conflict, Aeta, Cuthbert and their companions withdrew

to Melrose.

WILFRID AT THE SYNOD OF WHITBY

ilfrid's

leadership of the Roman faction in Northumbria was

confirmed by the Synod of Whitby. Their official leader was Agilbert, but he

quickly deferred to Wilfrid. The manner in which Wilfrid

conducted the debate ensured its twin outcomes. Colman,

the principal advocate of the Irish-Celtic position was

no match for Wilfrid's forensic brilliance. The Synod

decided that the Roman tradition should prevail.

Wilfrid's debating style also gave rise to the other

outcome. He was so robust, aggressive and dismissive of

the Irish-Celts that they felt deeply hurt and bruised.

It was their mission after all that had finally brought

Christianity to Northumbria in a way that endured. Now

they were being dismissed as 'ignorant' and irrelevant.

This hurt led to Bishop Colman leading many of his monks

from Lindisfarne, back to their mother house on Iona.

ilfrid's

leadership of the Roman faction in Northumbria was

confirmed by the Synod of Whitby. Their official leader was Agilbert, but he

quickly deferred to Wilfrid. The manner in which Wilfrid

conducted the debate ensured its twin outcomes. Colman,

the principal advocate of the Irish-Celtic position was

no match for Wilfrid's forensic brilliance. The Synod

decided that the Roman tradition should prevail.

Wilfrid's debating style also gave rise to the other

outcome. He was so robust, aggressive and dismissive of

the Irish-Celts that they felt deeply hurt and bruised.

It was their mission after all that had finally brought

Christianity to Northumbria in a way that endured. Now

they were being dismissed as 'ignorant' and irrelevant.

This hurt led to Bishop Colman leading many of his monks

from Lindisfarne, back to their mother house on Iona.

BISCOP AT THE TIME OF THE SYNOD

ust as Cuthbert

was totally identified with the Irish-Celtic church, so

Biscop had become a leading protagonist of the Roman

tradition. He was after all the first of his generation

to visit Rome. At the time of the synod however Biscop

was still on the continent, learning more of the various

monastic traditions there, and building up his

collection of sacred artefacts and books. It is unclear

as to whether his next move was prompted by the outcome

of the Synod. He may have seen new possibilities for the

resources he was amassing.

ust as Cuthbert

was totally identified with the Irish-Celtic church, so

Biscop had become a leading protagonist of the Roman

tradition. He was after all the first of his generation

to visit Rome. At the time of the synod however Biscop

was still on the continent, learning more of the various

monastic traditions there, and building up his

collection of sacred artefacts and books. It is unclear

as to whether his next move was prompted by the outcome

of the Synod. He may have seen new possibilities for the

resources he was amassing.

BISCOP ENTERS MONASTIC LIFE

iscop concluded

his continental tour with a further visit to Rome, and

here he finally concluded that he wished to enter the

religious life. He entered the monastery on St Honorat,

the outer of the two Isles of Lerins, situated in the

mouth of the bay of Cannes. He took the tonsure and the

name Benedict. (The name itself suggests

that Lerins may have been in the process of adopting

the Benedictine rule which was spreading throughout

Europe). The island monastery was moving from

the original eremitic individual cells with lauras to

the new more centralised cenobitic structure under

reforms instituted by St Aigulf. (The

abbot of Lerins believed that Biscop himself may have

been instrumental in this change, with the extensive

Continental experience he had gained.) Biscop

completed his two-year novitiate and, when a boat docked

at the island bound for Rome, he was permitted one final

pilgrimage.

iscop concluded

his continental tour with a further visit to Rome, and

here he finally concluded that he wished to enter the

religious life. He entered the monastery on St Honorat,

the outer of the two Isles of Lerins, situated in the

mouth of the bay of Cannes. He took the tonsure and the

name Benedict. (The name itself suggests

that Lerins may have been in the process of adopting

the Benedictine rule which was spreading throughout

Europe). The island monastery was moving from

the original eremitic individual cells with lauras to

the new more centralised cenobitic structure under

reforms instituted by St Aigulf. (The

abbot of Lerins believed that Biscop himself may have

been instrumental in this change, with the extensive

Continental experience he had gained.) Biscop

completed his two-year novitiate and, when a boat docked

at the island bound for Rome, he was permitted one final

pilgrimage.

BISCOP SECONDED TO THE SERVICE OF THEODORE

iscop's future

seemed to be ordained. He was destined, it seemed, to

live out his life as a monk on the Isles of Lerins, and

would, it seems, have been quite happy to do so. God had

another destiny planned for the saint. In Rome there was

a delegation from Britain led by Wighard the first

Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury, from the part of

England converted by Gregory’s Augustine. The Synod of

Whitby had created a great opportunity for church unity.

The British bishops, the remnant of the Romano-British

church, had previously refused the authority of

Canterbury. They were now willing to submit to the new

archbishop. Tragedy struck. Wighard and his party all contracted the

plague and died within days. The Pope appointed Theodore

of Tarsus, an elderly Greek scholar to the now vacant

role. Theodore did not speak Anglo-Saxon, nor was he

familiar with Continental travel. He needed a guide.

Benedict Biscop was on hand and ideally suited to the

role. Benedict was therefore required to accompany

Theodore and his party to Britain.

iscop's future

seemed to be ordained. He was destined, it seemed, to

live out his life as a monk on the Isles of Lerins, and

would, it seems, have been quite happy to do so. God had

another destiny planned for the saint. In Rome there was

a delegation from Britain led by Wighard the first

Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury, from the part of

England converted by Gregory’s Augustine. The Synod of

Whitby had created a great opportunity for church unity.

The British bishops, the remnant of the Romano-British

church, had previously refused the authority of

Canterbury. They were now willing to submit to the new

archbishop. Tragedy struck. Wighard and his party all contracted the

plague and died within days. The Pope appointed Theodore

of Tarsus, an elderly Greek scholar to the now vacant

role. Theodore did not speak Anglo-Saxon, nor was he

familiar with Continental travel. He needed a guide.

Benedict Biscop was on hand and ideally suited to the

role. Benedict was therefore required to accompany

Theodore and his party to Britain.

BISCOP BECOMES ABBOT OF CANTERBURY FOR A TIME

Abbot Hadrian, who had

accompanied the party, was detained in Paris. He had

been destined to take over the great abbey of

Canterbury. Upon arrival in Britain Theodore, who had

clearly been impressed with Biscop, invited him to

become acting Abbot. He fulfilled this role for two

years until Hadrian was able to arrive. Biscop's great

success as abbot made it unlikely that he would now

simply return to the life of a monk in Lerins. When

faced with any issues as to his spiritual destiny,

Biscop always acted in the same way. He made a further

pilgrimage to his beloved Rome. Here a future vision

must have formed in his mind.

BISCOP FOUNDS WEARMOUTH MONASTERY

iscop returned to

Britain via some of the monasteries, including Vienne,

where he had deposited artefacts and books. He gathered

his collection and set off back to Britain. He

eventually arrived back in his native Northumbria. Here

he found a new king on the throne. Oswy had died and was

replaced by King Egfrith. Biscop showed his collection

to the king. He was profoundly impressed and offered to

Biscop a gift of seventy hides of land, on which to

build a monastery on the north bank of the River Wear.

This Biscop, with the help of his imported glaziers and

stone masons, duly did in 74 AD. Later another royal

grant of land enabled the founding of another monastery

at Jarrow. Wilfrid was also building stone monasteries

in the continental style at Hexham and Ripon.

iscop returned to

Britain via some of the monasteries, including Vienne,

where he had deposited artefacts and books. He gathered

his collection and set off back to Britain. He

eventually arrived back in his native Northumbria. Here

he found a new king on the throne. Oswy had died and was

replaced by King Egfrith. Biscop showed his collection

to the king. He was profoundly impressed and offered to

Biscop a gift of seventy hides of land, on which to

build a monastery on the north bank of the River Wear.

This Biscop, with the help of his imported glaziers and

stone masons, duly did in 74 AD. Later another royal

grant of land enabled the founding of another monastery

at Jarrow. Wilfrid was also building stone monasteries

in the continental style at Hexham and Ripon.

CUTHBERT AND BISCOP IN THE AFTERMATH OF WHITBY

n the event the

two men, whose absence from Whitby seems to have been

most noteworthy, were to prove the most influential in

the journey of the church which followed the synod. The

very reasons for their absence were to be instrumental

in their future influence.

n the event the

two men, whose absence from Whitby seems to have been

most noteworthy, were to prove the most influential in

the journey of the church which followed the synod. The

very reasons for their absence were to be instrumental

in their future influence.

The humble obedience

which kept Cuthbert away from the synod was central to

Cuthbert's subsequent ministry on Lindisfarne. This

island community had been the spiritual heart of

Northumbria. Now it was the most damaged, depleted and

demoralised. If the spiritual life of the nation was not

to be irreparably damaged it was essential that the

Lindisfarne community be restored to health. Cuthbert

was appointed prior of Lindisfarne. His task was now to

promote that very humble obedience in the community. In

this his greatest asset was his personal example.

Bede tells us how

Cuthbert engaged with the delicate matter of introducing

a new rule to the community. He would present each

innovation at Chapter meetings, but the moment

opposition became heated, Cuthbert would simply

withdraw. He would then return the next day and begin

again his gentle process of persuasion. Gradually the

saint's persuasive skills began to bear fruit.

The monks of

Lindisfarne also recognised Cuthbert's own deep

qualities of obedience and humility. They knew of his reputation as a leading

figure in the Irish-Celtic church and saw how he had

willingly submitted to the new dispensation, seeing in

the Whitby decision the hand of God. Cuthbert's personal

holiness of his life also aided his influence. It was

said that he could not celebrate Mass nor hear

Confession without tears. His tireless devotions

exceeded even that of the offices prescribed. Cuthbert's

absence from Whitby and the reasons for it, greatly

enabled his subsequent central role in reconciling the

existing Northumbrian monastic network to new

disciplines and churchmanship.

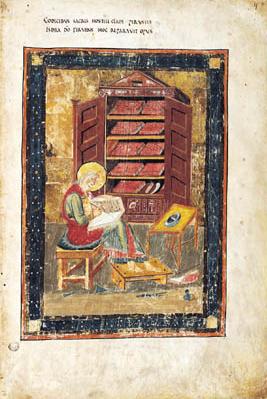

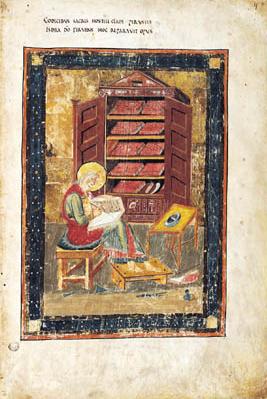

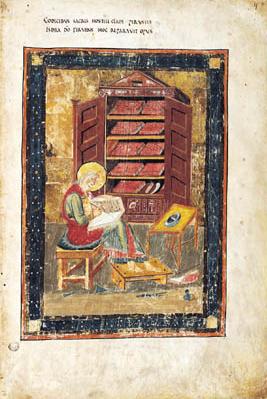

Biscop was in the

vanguard of the other stream which flowed from the

Whitby fountainhead. As well as the re-ordering of

existing monasteries there was also vigorous founding of

new communities in the Roman tradition. Wilfrid and

Biscop were equally energetic. There was an additional

dimension to Wearmouth/Jarrow which made it especially

influential. Biscop was at heart a great teacher and

enabler of others. He not only brought in glaziers and

masons from Gaul, he set up workshops where the local

people could be trained and take these skills further

afield. He later was to bring the Archcantor John from

St Peter's in Rome to Wearmouth/Jarrow. Folk came from

throughout the kingdom to learn the music and liturgy in

the Roman tradition. His greatest gift to the

Northumbrian church was surely his great library which

became one of the finest in Europe. This library in turn

enabled the monastery's super achievement in biblical

scholarship led by the Venerable Bede. The success and

influence of this great endeavour had been forged in

those years of preparation during which Biscop had

toured, collected and studied in continental

monasteries. An activity which had kept him away from

the Synod of Whitby.

BISCOP AND CUTHBERT: THE STREAMS MERGE.

nlike Wilfrid,

Biscop seems to have had a very high regard for the

achievement of the Irish Celtic church. This approbation

is mainly expressed in the work of the Venerable Bede.

In his Ecclesiastical History, Bede

speaks highly of the Irish-Celts and their achievement.

Indeed without his testimony we would know little of the

Lindisfarne monastery: of Aidan and his community. It is

inconceivable that Bede would have so written if this

were not in harmony with the views of his abbot and

first tutor Biscop.

nlike Wilfrid,

Biscop seems to have had a very high regard for the

achievement of the Irish Celtic church. This approbation

is mainly expressed in the work of the Venerable Bede.

In his Ecclesiastical History, Bede

speaks highly of the Irish-Celts and their achievement.

Indeed without his testimony we would know little of the

Lindisfarne monastery: of Aidan and his community. It is

inconceivable that Bede would have so written if this

were not in harmony with the views of his abbot and

first tutor Biscop.

The major

collaboration, which brought the two streams together,

concerned the life and death of Cuthbert. At the request

of Bishop Eadfrith of

Lindisfarne, Bede wrote a prose 'Life' of Cuthbert.

Together they were actively engaged in

promoting the cult of Cuthbert. Bishop Eadfrith himself

wrote the Lindisfarne Gospels, widely

believed to have been written in Cuthbert's honour.

These activities promoted a rich collaboration between

Lindisfarne and Wearmouth/Jarrow. The Latin text for the

Lindisfarne Gospels for example came

from a Wearmouth/Jarrow exemplar. The result was the

creative heart of what became known as the Golden Age of Northumbria. It saw

such an achievement in biblical scholarship, book

production and calligraphic attainment which has never

been surpassed. These works fuelled the missionary

endeavour in northern Germany that became widespread

across the libraries and monasteries of the Continent.

They produced a group of quite remarkable books in what

became known as the Italo-Northumbrian school of

biblical texts. These books include some of world

importance. They include:

The Lindisfarne

Gospels, the

Cuthbert Gospel of St John,

the 'Ceolfrith' Bible

-three fragments of the two other great Bibles produced

at Wearmouth/Jarrow (the Wollaston fragment/the Kingston Lacy

fragment and the Greenwell Leaf) and the fragmentary Durham

Gospels. In

addition, of course: the oldest complete Latin bible,

the purest reconstitution of St Jerome's Vulgate, the

book that some have described as the finest book ever

written: the Codex Amiatinus.

Rev. John McManners

BENEDETTO

BISCOP E CUTBERTO

DUE IMPORTANTI ASSENTI DAL SINODO DI WHITBY

INTRODUZIONE

l sinodo di

Whitby, tenuto nel 664, fu il grande evento centrale della “Storia ecclesiastica del

popolo inglese” di Beda. In questo sinodo il re Oswy prese

l'importante decisione che in futuro il suo regno si sarebbe

allineato al comportamento religioso dettato dalla chiesa di

Roma, invece che alla tradizione della chiesa

celtico-irlandese, che aveva

riportato la Nortumbria alla fede cristiana.

l sinodo di

Whitby, tenuto nel 664, fu il grande evento centrale della “Storia ecclesiastica del

popolo inglese” di Beda. In questo sinodo il re Oswy prese

l'importante decisione che in futuro il suo regno si sarebbe

allineato al comportamento religioso dettato dalla chiesa di

Roma, invece che alla tradizione della chiesa

celtico-irlandese, che aveva

riportato la Nortumbria alla fede cristiana.

Il

dibattito che si tenne al sinodo di Whitby è raccontato in

dettaglio da Beda e da Eddius Stephanus nella sua “Vita di

Vilfredo). I personaggi chiave sono delineati con cura;

questi includono Vilfredo, Agilberto, Cedd, Hilda e Colman

di Lindisfarne. Ci sono due sorprendenti assenze in questa

lista: Cutberto e il Biscop Benedetto.

L'IMPORTANZA

DELL'ASSENZA

a un punto di

vista storico posteriore la doppia assenza di queste figure

chiave non appare sorprendente; entrambi godevano di una

reputazione crescente, entrambi erano alla soglia di anni

fondamentali, entrambi si erano venuti identificando

fortemente con la direzione religiosa che rappresentavano.

Se si fosse familiari con la storia di questi due, ci si

sarebbe aspettati che fossero presenti al sinodo. Le ragioni

che possiamo individuare del 'Perché no?' sono istruttive;

ci spiegano il motivo per il quale i loro ruoli futuri

furono così efficaci, così influenti, e in ultima analisi

così complementari.

a un punto di

vista storico posteriore la doppia assenza di queste figure

chiave non appare sorprendente; entrambi godevano di una

reputazione crescente, entrambi erano alla soglia di anni

fondamentali, entrambi si erano venuti identificando

fortemente con la direzione religiosa che rappresentavano.

Se si fosse familiari con la storia di questi due, ci si

sarebbe aspettati che fossero presenti al sinodo. Le ragioni

che possiamo individuare del 'Perché no?' sono istruttive;

ci spiegano il motivo per il quale i loro ruoli futuri

furono così efficaci, così influenti, e in ultima analisi

così complementari.

L'assenza

dal sinodo può anche essere stata utile sia Biscop che a

Cutberto: essi non furono toccati né implicati negli scambi

piuttosto lesivi che Beda descrive; essi arrivarono ad

assumere un ruolo nuovo nella chiesa incontaminati rendendo

così possibile un nuovo inizio e la guarigione delle ferite.

Entrambi risultarono figure significative nella formazione

della chiesa di Nortumbria che emerse nel periodo

immediatamente seguente.

Dopo

Whitby il corso progressivo della chiesa di Nortumbria

cambiò; per un certo tempo questo scorreva in due canali

separati, ma complementari. E' mia

opinione che Cutberto e Biscop furono le due personalità più

influenti nel dare forma a questo sottile corso e

nell'ispirare il successivo mischiarsi delle acque.

IL

RUOLO DI BISCOP E CUTBERTO DOPO

IL SINODO

opo il sinodo

Cutberto dovette assumere un nuovo ruolo a Lindisfarne.

Questa isola soggetta alle maree aveva rappresentato proprio

il cuore della tradizione celtico-irlandese, non ché il sito

del primo monastero e scuola fondato da Aidano

e la sua comunità di monaci provenienti da Iona. E'

da questa isola che Aidano e i suoi monaci si sparsero nella

Nortumbria predicando, insegnando e, col tempo, fondando

monasteri affiliati per supportare il loro lavoro. La

decisione di Whitby e la conseguente partenza del vescovo

Colman con molti monaci lasciarono la comunità di

Lindisfarne impoverita e piuttosto demoralizzata; fu

Cutberto che ravvivò e dette nuovo indirizzo

alla spiritualità e alla scopo della comunità. Con la

sua azione creò un modello per altre fondazioni

celtico-irlandesi, come Melrose e Whitby, che ora dovettero

accettare il nuovo ordinamento.

opo il sinodo

Cutberto dovette assumere un nuovo ruolo a Lindisfarne.

Questa isola soggetta alle maree aveva rappresentato proprio

il cuore della tradizione celtico-irlandese, non ché il sito

del primo monastero e scuola fondato da Aidano

e la sua comunità di monaci provenienti da Iona. E'

da questa isola che Aidano e i suoi monaci si sparsero nella

Nortumbria predicando, insegnando e, col tempo, fondando

monasteri affiliati per supportare il loro lavoro. La

decisione di Whitby e la conseguente partenza del vescovo

Colman con molti monaci lasciarono la comunità di

Lindisfarne impoverita e piuttosto demoralizzata; fu

Cutberto che ravvivò e dette nuovo indirizzo

alla spiritualità e alla scopo della comunità. Con la

sua azione creò un modello per altre fondazioni

celtico-irlandesi, come Melrose e Whitby, che ora dovettero

accettare il nuovo ordinamento.

Biscop

fece parte di un'ondata di nuovi giovani entusiasti della

tradizione romana. La decisione presa a Whitby li rese

liberi di fondare nuovi monasteri sul modello continentale.

Essi costruirono in pietra e vetro importando artigiani

dalla Gallia per rendere possibile l'opera. Fondarono un

nuovo stile di monachesimo cenobitico di forte impronta

benedettina. I grandi monasteri gemelli di Wearmouth e

Jarrow, fondati da Biscop, sarebbero diventati una fucina di

spiritualità, erudizione biblica e produzione libraria;

divennero la casa di Beda il Venerabile.

Queste

due nuove correnti complementari della chiesa di Nortumbria

si fusero alla fine in modi che costituirono l'ispirazione e

il baluardo di quel risultato

sorprendente spirituale e culturale che divenne noto come

l'età d'oro della Nortumbria.

L'IMPORTANZA

DELLA

DECISIONE DI WHITBY

rima di

occuparci dei dettagli della vita di questi due importanti

santi, è necessario fare mente locale sul significato e

sull'impatto della decisione di Whitby. La “Storia

ecclesiastica” di Beda si

occupa di tre grandi temi: l'arrivo della fede cristiana

nelle isole britanniche; l'ascesa del regno di Nortumbria;

la formazione della nazione inglese. Tutti e tre si

incontrano a Whitby. In effetti Beda descrive l'arrivo della

fede in Britannia come un susseguirsi di ondate, le quali

raggiungono la terra e poi si ritirano. L'adozione della

tradizione romana a Whitby è l'ondata conclusiva, quella che

rimane nella storia successiva. Whitby rappresenta anche il

punto culminante dell'influsso della Nortumbria: introduce

la cosiddetta età d'oro della Nortumbria con le sue grandi

realizzazioni culturali, spirituali e intellettuali. La

decisione di Whitby esercitò anche grande influenza in tutte

le isole britanniche data la preminenza della Nortumbria tra

i regni anglosassoni del tempo. Dà inizio a un componente

chiave del nostro emergente carattere nazionale e serve a

riallinearci con la corrente principale della chiesa. Queste

strutture continentali si dovevano infine evolvere in ciò

che divenne per un certo tempo conosciuto come Cristianità.

rima di

occuparci dei dettagli della vita di questi due importanti

santi, è necessario fare mente locale sul significato e

sull'impatto della decisione di Whitby. La “Storia

ecclesiastica” di Beda si

occupa di tre grandi temi: l'arrivo della fede cristiana

nelle isole britanniche; l'ascesa del regno di Nortumbria;

la formazione della nazione inglese. Tutti e tre si

incontrano a Whitby. In effetti Beda descrive l'arrivo della

fede in Britannia come un susseguirsi di ondate, le quali

raggiungono la terra e poi si ritirano. L'adozione della

tradizione romana a Whitby è l'ondata conclusiva, quella che

rimane nella storia successiva. Whitby rappresenta anche il

punto culminante dell'influsso della Nortumbria: introduce

la cosiddetta età d'oro della Nortumbria con le sue grandi

realizzazioni culturali, spirituali e intellettuali. La

decisione di Whitby esercitò anche grande influenza in tutte

le isole britanniche data la preminenza della Nortumbria tra

i regni anglosassoni del tempo. Dà inizio a un componente

chiave del nostro emergente carattere nazionale e serve a

riallinearci con la corrente principale della chiesa. Queste

strutture continentali si dovevano infine evolvere in ciò

che divenne per un certo tempo conosciuto come Cristianità.

Molti

di questi esiti non si sarebbero sviluppati nel modo in cui

lo furono, o al punto in cui giunsero, se non fosse stato

per i contributi chiave di Cutberto e Biscop. Questi

ministri, che si susseguirono, sembravano progredire in

campi separati ma paralleli; alla fine ci dovette essere una

confluenza che arricchì la chiesa e la nazione, ed ebbe

grandi conseguenze sia in Britannia sia nel continente. I

ruoli che Cutberto e Biscop assunsero sono radicati negli

anni della loro formazione cristiana e i diversi cammini che

intrapresero in gioventù. La vita di Cutberto è piuttosto

ben conosciuta ed è stata ampiamente documentata; Biscop è

una figura più oscura e la maggior parte di coloro che lo

incontrano sentono che la sua vita merita maggiore

celebrazione.

I

PRIMI ANNI DI VITA DI CUTBERTO

ncontriamo per

la prima volta Cutberto nelle colline di Lammermuir, in

quello che è oggi il terreno confinante con la Scozia;

sembra fosse di ascendenza Britanno-celtica. Il fatto che

possedesse un cavallo. Con il quale viaggiava per ampio

raggio, sembrerebbe indicare che fosse di famiglia nobile.

Uno o due episodi profetici illuminano la sua fanciullezza

ed è chiaro che sta già pensando al suo futuro in termini

religiosi. Un episodio formativo accade

di notte mentre

sorveglia le pecore con i suoi compagni. (Lupi e altri

predatori sono ancora comuni nella campagna della

Nortumbria). Cutberto già mostra la sua inclinazione

spirituale, dato che è sveglio a lodare Dio.; ha una visione

di angeli; sveglia i suoi compagni. Sono testimoni di una

fuga di angeli che trasportano un 'globo di fuoco'; si

rendono conto che stanno vedendo l'anima di un grande uomo

trasportata in cielo. Più tardi chiedendo che al vicino

monastero di Melrose vengono a sapere che Aidano di

Lindisfarne è morto proprio nel momento della visione dei

pastori.

ncontriamo per

la prima volta Cutberto nelle colline di Lammermuir, in

quello che è oggi il terreno confinante con la Scozia;

sembra fosse di ascendenza Britanno-celtica. Il fatto che

possedesse un cavallo. Con il quale viaggiava per ampio

raggio, sembrerebbe indicare che fosse di famiglia nobile.

Uno o due episodi profetici illuminano la sua fanciullezza

ed è chiaro che sta già pensando al suo futuro in termini

religiosi. Un episodio formativo accade

di notte mentre

sorveglia le pecore con i suoi compagni. (Lupi e altri

predatori sono ancora comuni nella campagna della

Nortumbria). Cutberto già mostra la sua inclinazione

spirituale, dato che è sveglio a lodare Dio.; ha una visione

di angeli; sveglia i suoi compagni. Sono testimoni di una

fuga di angeli che trasportano un 'globo di fuoco'; si

rendono conto che stanno vedendo l'anima di un grande uomo

trasportata in cielo. Più tardi chiedendo che al vicino

monastero di Melrose vengono a sapere che Aidano di

Lindisfarne è morto proprio nel momento della visione dei

pastori.

Questa

esperienza conferma la chiamata di Cutberto che entra nella

vita monastica a Melrose. La scelta di Melrose sarà senza

dubbio stata guidata dalla sua prossimità, ma Beda ci dice

anche che Cutberto è attratto dalla reputazione di Boisil

come insegnante. Boisil è il priore di Melrose sotto l'abate

Eata. Boisil si trova alla porta del monastero quando

Cutberto arriva e profetizza un grande futuro per il giovane

novizio. Durante gli anni formativi trascorsi a Melrose,

Cutberto rivela un rimarchevole zelo per la disciplina

spirituale e la passione per portare il Vangelo nei luoghi

più remoti. Cutberto viene presto riconosciuto come uomo di

spiritualità eccezionale;comincia a mostrare doni di

profezia e taumaturgia. Quando l'abate Eata è invitato a

fondare un altro monastero a Ripon, egli porta con sé

Cutberto che nomina maestro degli ospiti. Questa iniziativa

fallisce(Le ragioni sono istruttive e saranno esaminate

in seguito).Al loro ritorno a Melrose apprendono che

Boisil, l'amatissimo maestro di Cutberto sta morendo; al suo

trapasso Cutberto è nominato priore. E' chiaro che le sante qualità di Cutberto sono

ora ampiamente riconosciute; la sua reputazione si estende

ben oltre i confini di Melrose; ad esempio è invitato dalla

badessa Ebbe a fare una visita di incoraggiamento al suo

monastero di Coldingham.

CUTBERTO

AL TEMPO DI WHITBY

osì nel 664

Cutberto era una prominente e ampiamente rispettata figura

con un importante futuro nella chiesa di Nortumbria. Inoltre

il suo ministero era imbevuto e radicato nella tradizione

celtico-irlandese; il suo abate Aeta era stato allievo di

Aidano. Cutberto aveva portato questa tradizione a livelli

ancora più alti ed è possibile sostenere che ne fu l'esempio

maggiore.

osì nel 664

Cutberto era una prominente e ampiamente rispettata figura

con un importante futuro nella chiesa di Nortumbria. Inoltre

il suo ministero era imbevuto e radicato nella tradizione

celtico-irlandese; il suo abate Aeta era stato allievo di

Aidano. Cutberto aveva portato questa tradizione a livelli

ancora più alti ed è possibile sostenere che ne fu l'esempio

maggiore.

Le

sue discipline erano rigorose; la sua amicizia

con gli animali domestici che condividevano il suo

lavoro e con le creature selvatiche che incontrava erano l'espressione maggiore

dell'allinearsi celtico-irlandese con la grana del mondo

della natura. Sarebbe difficile concepire un avvocato più

avvincente. Tuttavia Cutberto non fu presente al sinodo di

Whitby; le sue tre biografie non ne registrano la presenza,

e il suo nome non compare nella lista dei delegati.

Possiamo

solo speculare sul motivo per il quale Cutberto, il

quintessenziale santo celtico-irlandese,

non fu presente al sinodo. La più importante e

probabile ragione è la profonda umiltà del santo; al cuore

di questa qualità si trovava la sua profonda obbedienza: non

era a Whitby perché non gli era stato chiesto di andare. Un

uomo più ambizioso, avvertendo la natura storica del sinodo,

avrebbe potuto chiedere di andare o tentare di manipolare

per esservi presente. Tali caratteristiche non facevano

parte del carattere di Cutberto; la sua passione era essere

con Dio e fare il suo lavoro. (Molti anni dopo gli fu

chiesto di essere vescovo di Lindisfarne al sinodo di

Twyford. Si sottrasse a ogni blandizie, anche da parte del

re, finché non si rese conto che la decisione unanime del

sinodo significava che questa era l'intenzione di Dio per

lui).Era obbediente quando gli si chiedeva di

assumersi una responsabilità, ma non aveva ambizioni

mondane.

I

PRIMI ANNI DI VITA DI BISCOP BADUCING

iscop era

originariamente noto con il nome di famiglia Baducing.

Emerge per la prima volta nelle pagine della storia alla

corte del re Oswy, dove Biscop servì il re con distinzione;

tra i suoi ruoli può esserci stato il servizio militare.

Dopo alcuni anni Oswy era sul

punto di dare a Biscop una concessione di terra come

ricompensa per il suo fedele servizio; a questo punto Beda

ci dice che Biscop decise di dedicare la sua vita a Cristo;

la lingua di Beda è simile a quella che usa per descrivere

qualcuno che sta per abbracciare la vita religiosa.

L'intenzione di Biscop tuttavia non è quella di entrare in

monastero; la sua grande aspirazione è visitare Roma.

Durante il tempo trascorso a corte Biscop aveva saputo della

grande città e delle sue meravigliose chiese. Così abbandonò

la corte e l'opportunità di godere della vita privilegiata

di un nobile nella Nortumbria anglosassone.

iscop era

originariamente noto con il nome di famiglia Baducing.

Emerge per la prima volta nelle pagine della storia alla

corte del re Oswy, dove Biscop servì il re con distinzione;

tra i suoi ruoli può esserci stato il servizio militare.

Dopo alcuni anni Oswy era sul

punto di dare a Biscop una concessione di terra come

ricompensa per il suo fedele servizio; a questo punto Beda

ci dice che Biscop decise di dedicare la sua vita a Cristo;

la lingua di Beda è simile a quella che usa per descrivere

qualcuno che sta per abbracciare la vita religiosa.

L'intenzione di Biscop tuttavia non è quella di entrare in

monastero; la sua grande aspirazione è visitare Roma.

Durante il tempo trascorso a corte Biscop aveva saputo della

grande città e delle sue meravigliose chiese. Così abbandonò

la corte e l'opportunità di godere della vita privilegiata

di un nobile nella Nortumbria anglosassone.

Biscop

si diresse a sud verso il Kent per la traversata al

continente e visitò la corte del re del Kent Erconbert. Quì

incontrò un altro potenziale viaggiatore non altro che il

giovane Vilfredo, che era il protetto della regina di

Nortumbria; come Biscop anche lui aveva concepito il

desiderio di visitare Roma. Erconbert del Kent doveva

fedeltà alla Nortumbria e si era impegnato a che Vilfredo,

che aveva solo diciotto anni, non avrebbe avuto il permesso

di viaggiare a meno che non si trovassero dei compagni

adatti. Biscop, che aveva venticinque anni e molta più

esperienza di vita, fu reputato adatto.

Viaggiare

attraverso l'Europa a quei tempi era difficile e pericoloso;

il viaggio a Roma poteva durare fino a un anno. Le uniche

strade erano i resti di quelle romane e si potevano

incontrare briganti e bestie feroci sulla via. Gli uomini

progredirono bene finché non giunsero alla città di Lione.

Qui il vescovo Annamundus si interessò molto al brillante e

carismatico Vilfrido.; era così entusiasta del giovane che

voleva farne il suo erede. Il trattare Vilfredo come una

celebrità causò una rottura con Biscop; egli voleva

estendere il periodo della permanenza

a Lione. Biscop rimase fermo nel suo proposito, così si

venne a una divisione. Biscop proseguì per Roma, dove

probabilmente fu il primo anglosassone libero a entrare in

città.

BISCOP

A ROMA

Roma

Biscop stava al monastero sul monte Celio fondato da

Gregorio Magno; da questa base visitò le tombe di Pietro e

Paolo. Rimase colpito dalle glorie architettoniche e

culturali della città: la maggior parte dei grandi edifici imperiali, come il Foro,

il Colosseo e il Circo Massimo, era rimasta intatta. Inoltre

vi erano molte chiese, e che chiese! Erano costruite in

pietra con finestre di vetro istoriate. Gli interni

vibravano di vita: affreschi, pavimenti di mattonelle,

mosaici, dipinti e icone riempivano le chiese di colore;

candele e incenso rendevano ancora più ricca l'esperienza

sensoriale. Vi era una forte influenza bizantina che si

aggiungeva all'opulenza e al mistero della spiritualità che

incontrava. Biscop fu completamente sopraffatto da questa

esperienza; ritornò in Britannia del tutto convertito ai

meriti della tradizione romana. Riferì con entusiasmo la sua

esperienza e, forte della recente esperienza in prima

persona, emerse rapidamente come uno dei capi del gruppo

favorevole a Roma.

Roma

Biscop stava al monastero sul monte Celio fondato da

Gregorio Magno; da questa base visitò le tombe di Pietro e

Paolo. Rimase colpito dalle glorie architettoniche e

culturali della città: la maggior parte dei grandi edifici imperiali, come il Foro,

il Colosseo e il Circo Massimo, era rimasta intatta. Inoltre

vi erano molte chiese, e che chiese! Erano costruite in

pietra con finestre di vetro istoriate. Gli interni

vibravano di vita: affreschi, pavimenti di mattonelle,

mosaici, dipinti e icone riempivano le chiese di colore;

candele e incenso rendevano ancora più ricca l'esperienza

sensoriale. Vi era una forte influenza bizantina che si

aggiungeva all'opulenza e al mistero della spiritualità che

incontrava. Biscop fu completamente sopraffatto da questa

esperienza; ritornò in Britannia del tutto convertito ai

meriti della tradizione romana. Riferì con entusiasmo la sua

esperienza e, forte della recente esperienza in prima

persona, emerse rapidamente come uno dei capi del gruppo

favorevole a Roma.

BISCOP

SUL CONTINENTE

questo

punto una strana lacuna di dieci anni appare nella sua

biografia secondo Beda. La maggior parte degli studiosi

concordano sul fatto che probabilmente trascorse questo

periodo visitando i monasteri continentali. Egli dice della

sua fondazione posteriore di avere introdotto una regola

distillata dall'esperienza di diciassette monasteri

continentali. Date le difficoltà del viaggiare, l'unico

periodo di tempo sufficiente per fare un viaggio così

prolungato fu la lacuna di dieci anni. Quest'assenza

significò che la direzione de4l nuovo movimento romano cadde

in altre mani. Inoltre non era

in Britannia quando Vilfredo infine fece ritorno.

questo

punto una strana lacuna di dieci anni appare nella sua

biografia secondo Beda. La maggior parte degli studiosi

concordano sul fatto che probabilmente trascorse questo

periodo visitando i monasteri continentali. Egli dice della

sua fondazione posteriore di avere introdotto una regola

distillata dall'esperienza di diciassette monasteri

continentali. Date le difficoltà del viaggiare, l'unico

periodo di tempo sufficiente per fare un viaggio così

prolungato fu la lacuna di dieci anni. Quest'assenza

significò che la direzione de4l nuovo movimento romano cadde

in altre mani. Inoltre non era

in Britannia quando Vilfredo infine fece ritorno.

ULTERIORI

AVVENTURE DI VILFREDO

ilfredo rimase

a Lione altri sei mesi dopo la partenza di Biscop prima di

partire in ritardo per Roma, qui conobbe l'arcidiacono

Bonifacio, che lo introdusse al papa. Venne chiaramente

identificato come un giovane promettente e fece ritorno a

Lione pieno di rinnovato entusiasmo. Prese la tonsura e

divenne monaco nella tradizione romana.

Poco dopo la regina Baldhild iniziò a perseguitare i

cristiani; invece di imbarcarsi in un massacro, scelse

l'esecuzione di certi vescovi; Annumundus fu accusato e in

seguito a un processo fittizio fu condannato a morte. Quando

fu portato al luogo dell'esecuzione, il suo protetto

Vilfredo insistette per accompagnarlo. Sul luogo

dell'esecuzione Vilfredo si spogliò e

si presentò al carnefice; la sua gioventù e l'aspetto

anglosassone lo tradirono; si fecero indagini e quando fu

chiaro che il giovane era un visitatore proveniente di

recente dalla Britannia, si rifiutarono di giustiziarlo con

Annamundus. Dopo la morte del suo mentore, le autorità

posero Vilfredo su una barca ed egli ritornò, passando per

Marsiglia, in Britannia. (Il successivo ministero di

Vilfredo è spesso criticato, ma quello che questo episodio

dimostra è che era un giovano molto coraggioso)

ilfredo rimase

a Lione altri sei mesi dopo la partenza di Biscop prima di

partire in ritardo per Roma, qui conobbe l'arcidiacono

Bonifacio, che lo introdusse al papa. Venne chiaramente

identificato come un giovane promettente e fece ritorno a

Lione pieno di rinnovato entusiasmo. Prese la tonsura e

divenne monaco nella tradizione romana.

Poco dopo la regina Baldhild iniziò a perseguitare i

cristiani; invece di imbarcarsi in un massacro, scelse

l'esecuzione di certi vescovi; Annumundus fu accusato e in

seguito a un processo fittizio fu condannato a morte. Quando

fu portato al luogo dell'esecuzione, il suo protetto

Vilfredo insistette per accompagnarlo. Sul luogo

dell'esecuzione Vilfredo si spogliò e

si presentò al carnefice; la sua gioventù e l'aspetto

anglosassone lo tradirono; si fecero indagini e quando fu

chiaro che il giovane era un visitatore proveniente di

recente dalla Britannia, si rifiutarono di giustiziarlo con

Annamundus. Dopo la morte del suo mentore, le autorità

posero Vilfredo su una barca ed egli ritornò, passando per

Marsiglia, in Britannia. (Il successivo ministero di

Vilfredo è spesso criticato, ma quello che questo episodio

dimostra è che era un giovano molto coraggioso)

VILFREDO

IN NORTUMBRIA

l suo ritorno

Vilfredo non perse tempo a diventare un campione in vista

della tradizione romana; si

mise con Aldredo,il figlio del re Oswy, e sotto-re di Deira.

Ci fu un primo episodio che faceva presagire cosa sarebbe

avvenuto. Avendo già invitato Aeta a fondare un nuovo

monastero a Ripon (questa è l'occasione in cui, come già

detto, Cutberto divenne maestro degli ospiti), Aelredo

proseguì inserendo Vilfredo come capo della comunità. (Non

è chiaro a chi spettasse in ultima istanza l'autorità) Divenne

ben presto chiaro che Vilfredo non avrebbe accettato

compromessi tra le due tradizioni e così, piuttosto che

permettere il conflitto, Aeta, Cutberto e i loro compagni si

ritirarono a Melrose.

l suo ritorno

Vilfredo non perse tempo a diventare un campione in vista

della tradizione romana; si

mise con Aldredo,il figlio del re Oswy, e sotto-re di Deira.

Ci fu un primo episodio che faceva presagire cosa sarebbe

avvenuto. Avendo già invitato Aeta a fondare un nuovo

monastero a Ripon (questa è l'occasione in cui, come già

detto, Cutberto divenne maestro degli ospiti), Aelredo

proseguì inserendo Vilfredo come capo della comunità. (Non

è chiaro a chi spettasse in ultima istanza l'autorità) Divenne

ben presto chiaro che Vilfredo non avrebbe accettato

compromessi tra le due tradizioni e così, piuttosto che

permettere il conflitto, Aeta, Cutberto e i loro compagni si

ritirarono a Melrose.

VILFREDO

AL SINODO DI WHITBY

a conduzione

della fazione romana di Vilfredo fu confermata dal sinodo di

Whitby; il capo ufficiale era Agilberto, ma questi subito si

sottomise a Vilfredo. Il modo in cui Vilfredo condusse il

dibattito assicurò i suoi due risultati. Colman, il

principale sostenitore della posizione celtico-irlandese non

era un valido oppositore per la brillantezza avvocatesca di

Vilfredo: il sinodo decise che la tradizione romana dovesse

prevalere. Lo stile oratorio di Vilfredo produsse anche un

altro risultato. Eli fu così robusto, aggressivo e

sprezzante dei celtico-irlandesi che questi si sentirono

profondamente offesi e danneggiati.

In fin dei conti era stata la loro missione che aveva infine

portato la cristianità nella Nortumbria in modo definitivo;

ora erano respinti come 'ignoranti' e irrilevanti. Questo

ferita fece sì che il vescovo Colman conducesse molti dei

suoi monaci via da Lindisfarne per ritornare alla casa madre

di Iona.

a conduzione

della fazione romana di Vilfredo fu confermata dal sinodo di

Whitby; il capo ufficiale era Agilberto, ma questi subito si

sottomise a Vilfredo. Il modo in cui Vilfredo condusse il

dibattito assicurò i suoi due risultati. Colman, il

principale sostenitore della posizione celtico-irlandese non

era un valido oppositore per la brillantezza avvocatesca di

Vilfredo: il sinodo decise che la tradizione romana dovesse

prevalere. Lo stile oratorio di Vilfredo produsse anche un

altro risultato. Eli fu così robusto, aggressivo e

sprezzante dei celtico-irlandesi che questi si sentirono

profondamente offesi e danneggiati.

In fin dei conti era stata la loro missione che aveva infine

portato la cristianità nella Nortumbria in modo definitivo;

ora erano respinti come 'ignoranti' e irrilevanti. Questo

ferita fece sì che il vescovo Colman conducesse molti dei

suoi monaci via da Lindisfarne per ritornare alla casa madre

di Iona.

BISCOP

AL TEMPO DEL SINODO

roprio come

Cutberto si identificava totalmente con la chiesa

celtico-irlandese, così Biscop era diventato un importante

protagonista della tradizione romana; era stato dopo tutto

il primo della sua generazione a visitare Roma. Al tempo del

sinodo tuttavia Biscop era ancora sul continente, per

apprendervi di più sulle varie tradizioni monastiche e

mettere insieme la sua collezione di artefatti e libri

sacri. Non è chiaro se la sua mossa successiva fu causata

dal risultato del sinodo. Può avere intravisto nuove

possibilità per le risorse che andava ammucchiando.

roprio come

Cutberto si identificava totalmente con la chiesa

celtico-irlandese, così Biscop era diventato un importante

protagonista della tradizione romana; era stato dopo tutto

il primo della sua generazione a visitare Roma. Al tempo del

sinodo tuttavia Biscop era ancora sul continente, per

apprendervi di più sulle varie tradizioni monastiche e

mettere insieme la sua collezione di artefatti e libri

sacri. Non è chiaro se la sua mossa successiva fu causata

dal risultato del sinodo. Può avere intravisto nuove

possibilità per le risorse che andava ammucchiando.

BISCOP

ABBRACCIA LA VITA MONASTICA

iscop concluse

il suo viaggio sul continente con un ulteriore visita a

Roma, e qui finalmente venne alla decisione che desiderava

abbracciare la vita religiosa. Entrò a far parte del

monastero di san Onorato, la più esterna delle isole di

Lerins, situate nella foce della baia di Cannes: prese la

tonsura e il nome di Benedetto. (Il nome

stesso suggerisce che Lerins possa essere stato in

procinto di adottare la regola benedettina che si stava

spargendo in tutta Europa). Il monastero sull'isola

stava cambiando dalla originale struttura a celle eremitiche

individuali alla nuova struttura cenobitica più

centralizzata con le riforme istituite da san Aigulf. (L'abate

di

Lerins riteneva che lo stesso Biscop avesse potuto essere

lo strumento di questo cambiamento, data la grande

esperienza continentale che aveva acquisito).Biscop

completò il suo noviziato di due anni e, quando una barca

diretta a Roma attraccò all'isola, ebbe il permesso di fare

un ultimo pellegrinaggio.

iscop concluse

il suo viaggio sul continente con un ulteriore visita a

Roma, e qui finalmente venne alla decisione che desiderava

abbracciare la vita religiosa. Entrò a far parte del

monastero di san Onorato, la più esterna delle isole di

Lerins, situate nella foce della baia di Cannes: prese la

tonsura e il nome di Benedetto. (Il nome

stesso suggerisce che Lerins possa essere stato in

procinto di adottare la regola benedettina che si stava

spargendo in tutta Europa). Il monastero sull'isola

stava cambiando dalla originale struttura a celle eremitiche

individuali alla nuova struttura cenobitica più

centralizzata con le riforme istituite da san Aigulf. (L'abate

di

Lerins riteneva che lo stesso Biscop avesse potuto essere

lo strumento di questo cambiamento, data la grande

esperienza continentale che aveva acquisito).Biscop

completò il suo noviziato di due anni e, quando una barca

diretta a Roma attraccò all'isola, ebbe il permesso di fare

un ultimo pellegrinaggio.

BISCOP

DISTACCATO AL SERVIZIO DI TEODORO

l futuro di

Biscop appariva deciso; era destinato, sembrava, a vivere la

sua vita come monaco sulle isole di Lerins e pare che ne

sarebbe stato ben contento; Dio aveva pianificato un altro

destino per il santo. A Roma c'era una delegazione dalla

Britannia con a capo Wighard, il primo arcivescovo

anglo-sassone di Canterbury. Il sinodo di Whitby aveva

creato una grande opportunità per l' unità della chiesa. I

vescovi britannici , il resto della chiesa

romano-britannica, avevano in un primo momento rifiutato

l'autorità di Canterbury; ora erano desiderosi di

sottomettersi al nuovo arcivescovo. Avvenne una tragedia;

Wighard e il suo comitato contrassero la peste e morirono in

pochi giorni. Il papa nominò Teodoro di Tarso, un anziano