LA CITTA` E IL LIBRO

I

CONVEGNO

INTERNAZIONALE

ALLA CERTOSA DI

FIRENZE

30, 31 MAGGIO, 1

GIUGNO 2001

THE CITY AND THE BOOK

I

INTERNATIONAL

CONGRESS

IN FLORENCE'S

CERTOSA

30, 31 MAY, 1

JUNE 2001

ATTI/ PROCEEDINGS

SECTION I. L'ALFABETO E LA BIBBIA

I. THE

ALPHABET AND THE BIBLE

Incisione, Bruno Vivoli

Repubblica di San Procolo, 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION I: ALPHABET AND BIBLE: Preface, prof.ssa Julia Bolton Holloway, Biblioteca e Bottega Fioretta Mazzei (English, italiano) || Fioretta Mazzei and the City, Giannozzo Pucci (English) || Fioretta Mazzei and the Book, dott.ssa Giovanna Carocci (italiano, English) || The Codex Amiatinus: Initiatives of the Laurentian Library, dott.ssa Franca Arduini, Laurentian Library (italiano, English) || The Alphabet: Origins and Diffusion, prof.ssa Maria Giulia Amadasi, University of Rome (italiano, English) || Some Observations on the Composition of the Bible, Osservazioni sulla composizione della Bibbia, prof.ssa Ida Zatelli, Università di Firenze (italiano, English) || The Hebrew Bible in the First Millennium, prof. Giuliano Tamani, Università Ca' Foscari, Venice (italiano, English) ||

SECTION II: THE CHRISTIAN BIBLE: The CODEX SINAITICUS and the CODEX ALEXANDRINUS: A Tale of Four Cities, Dr Scot McKendrick, The British Library (unavailable, non disponibile) || Jerome and His Learned Lady Disciples, prof. Claudio Moreschini, Università di Pisa (italiano, English) || Bishop Wulfila and the Codex Argenteus, Professor James Marchand, University of Illinois (English, italiano) || Cassiodorus, dott.ssa Luciana Cuppo Csaki, Societas internationalis pro Vivario (italiano, English) ||

SECTION III: IRISH PSALTERS AND BIBLES: Irish Psalters and Bibles, The CATHACH, THE BOOK OF KELLS, The Manuscripts, Dr Bernard Meehan, Trinity College Library, Dublin (English, italiano) || Irish Psalters and Bibles, The Cathach, The Book of Kells, The Texts, Professor Martin McNamara, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (English) ||The Irish peregrini in Tuscany, Professor Màire Herbert, University of Cork (English, italiano) ||

SECTION IV: THE BIBLE IN ENGLAND AND ICELAND: The CODEX AMIATINUS, prof.ssa Lucia Castaldi, S.I.S.M.E.L., Florence (italiano, English) ||The Celtic and Scandinavian Loan Words in the Lindisfarne Glosses, David Moreno, University of Moraga (English, italiano) || The Lichfield Gospels, Canon Tony Barnard, Lichfield Cathedral (English, italiano) || The Dream of the Rood, Ruthwell/Vercelli, prof. Domenico Pezzini (English) ||Life of St Gregory, A.D. 713, Whitby/St Gall, Julia Bolton Holloway, Biblioteca e Bottega Fioretta Mazzei (English, italiano) || The Bible in Iceland, Professor Svanhildur Oskarsdottir, Arni Magnusson Institute, Reykjavik (English, italiano) ||

SECTION V: THE BIBLE IN RUSSIA, SPAIN, ITALY: The Gospels in the Byzantine-Slavic World, prof. Marcello Garzaniti, Università di Studi di Firenze (italiano, English) || Alphabet and Bible in Russia, Juliana Dresvina, University of Moscow (English) ||The Apostles' Diaspora and the Relation of the Beatus with Islam, dott.ssa Angela Franco, Museum of Antiquities, Madrid (Spanish) || Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained: Multiple Texts and Multiple Communities, Professor Regina Schwartz, Northwestern University (English, italiano) || Monastic lectio divina, Padre Priore Luigi De Candido, O.S.M., Monte Senario (italiano, English)

Map

and Time Line

Book Fair

Florin

You can search a particular reference term within this website, http://www.florin.ms, using the search engine below:

|

Search WWW Search www.florin.ms |

{ This international congress, the first of three to be held in Florence, combines two themes, the spread of the alphabet and, in its wake, of the Bible; both Semitic, the first Phoenician in its origin, the second, Hebraic, and related to each other; both originating outside of Europe, yet giving Europe culture and civilization, flooding and ebbing like a great river of life-giving water across our Continent, without which we would be lost in illiteracy and barbarism.

Questo convegno internazionale, il primo di tre che si terranno a Firenze, coniuga due temi, la diffusione dell'alfabeto e, sulle sue orme, la diffusione della Bibbia. Sia l'alfabeto sia la Bibbia sono semitici, l'alfabeto è di origine fenicia, la Bibbia è di origine ebraica, e l'uno è connesso all'altra. Entrambi hanno avuto origine al di fuori dell'Europa e tuttavia hanno dato all'Europa cultura e civilizzazione, crescendo e rifluendo come una immensa marea di acqua vivificante per tutto il nostro Continente. Senza di essi saremmo perduti nell'analfabetismo e preda della barbarie.

Evolution of the Alphabet

From http://www.wam.umd.edu/~rfradkin/latin.html

The names of our letters, in Hebrew, Arabic and Greek, are the same, despite many centuries, despite diverse languages, despite diverse races, in a shared technology:

I nomi delle nostre lettere, in ebraico, arabo, e greco, sono i medesimi a dispetto dei secoli, delle diverse lingue, e delle diverse razze, in un condiviso sistema tecnologico:

|| Aleph, Alef, Alpha || Beth, Ba, Beta || Gimel, Geem, Gamma|| Daleth, Dal, DeltaTheir names are pictographic and polyvalent, aleph being ox and one, beth, tent/house and 2, gimel , camel and 3, daleth, door and 4, he, whistle and 5, vau, nail and 6, zayin, weapon and 7, kheth, fence and 8, teth, twisting and 9, yod, hand and 10, kaph, palm and 20, lamed, ox-goad and 30, mem, water and 40, nun , fish and 50, samech , support and 60, ayin, eye and 70, pe/phe, mouth and 80, tzadi, hook and 90, qoph , coif and 100, resh, head and 200, sin/shin, tooth and 300, tau, cross and 400. We, as the three Peoples of the Book, are one family in this ancient technology of alphabet and mathematics. What difference is there between a clay cylinder incised with cuneiform symbols and a floppy disk? Torah, Gospel, Koran are books that communicate across space and time, in a past, present, future Internet. At the end of our conference we visited Fiesole, from which Troy was founded by Dardanus, from which Rome was founded by Aeneas, and from which Florence was founded by Julius Caesar, seeing there Etruscan inscriptions resembling Viking runes, for these, too, are Phoenician in origin. The ' Dream of the Rood ' was first inscribed in Anglo-Saxon runes on a stone cross beyond Hadrian's Wall in Ruthwell, Scotland, then in Roman letters on parchment in a manuscript left by a pilgrim at Vercelli, Italy. Geoffrey Chaucer, who visited Florence in the fourteenth century, tells us in the Canterbury Tales of the pagan Anglo-Saxon King Alla of Northumberland using a Celtic Bible, 'A Britoun book, written with Evaungiles', combining that tale with Constance's voyage also to Islam ('Man of Law's Tale', II.B.666). First Wulfila, then Cyril and Methodius, invented quasi-new alphabets for translating the Bible into Gothic, into Slavic. Fyodor Dosteivsky, writing The Idiot in Florence in the nineteenth century, describes his princely hero come home to Russia from Switzerland, writing the signature in Cyrillic of the fourteenth-century abbot Paphnutius, whose name mirror-reflects that of the Desert Father in the Egyptian Thebaid. Our alphabet reached India, reached Malaya, stopping short at China. Today, in the streets of Florence, in the San Lorenzo market, Chinese immigrants will paint for you in exquisite pictographic calligraphy, worthy of a Laurentian Library manuscript, our Roman Alphabet as they learn it, where A can be a pagoda, B, bamboo, C, a crustacean:

|| Zayin, Zai, Zeta|| Teth, Thal, Theta|| Kaph, Kaf, Kappa || Lamed, Lam, Lamda

|| Mem, Meem, Mu|| Nun, Nun, Nu || Rhesh, Ra, Rho || Sin, Seen, Sigma

|| Tau, Toa, Tau||

I loro nomi sono pittografici e polivalenti: l'aleph

equivale a bue e uno, la beth significa tenda/casa e

corrisponde a due, la gimel significa cammello e

rappresenta il numero tre, la lettera daleth significa

porta e corrisponde a 4, la lettera he significa alito-suono

e corrisponde a 5, la vau significa chiodo e

corrisponde a 6, la zayin significa arma ed equivale a

7, la kheth equivale a steccato e 8, la teth a

torsione e 9, la yod a mano e 10, la lettera kaph

al palmo della mano e a 20, la lettera lamed a pungolo

e 30, la lettera mem ad acqua e a 40, la nun a

pesce e 50, la samech a sostegno/fiducia e 60, la ayin a occhio e 70, pe/phe

significa bocca e 80, la tzadi gancio e 90, la

qoph calotta e

100, la lettera resh testa e 200, la sin/shin,

dente e 300, la tau, croce e 400.

Noi, in quanto i tre

Popoli della Bibbia, siamo un'unica famiglia in questo antico

sistema tecnologico che combina alfabeto e matematica. Qual è

la differenza tra un disco di argilla inciso con simboli

cuneiformi ed un dischetto? La Torah, il Vangelo, il Corano

sono libri che comunicano attraverso lo spazio e il tempo, nel

passato, nel presente, nel futuro di Internet. A conclusione

del nostro convegno abbiamo visitato Fiesole (da Fiesole

Dardanus fondò Troia, Enea fondò da Troia Roma, e da

quest'ultima Giulio Cesare fondò Firenze) e lì abbiamo potuto

vedere delle iscrizioni etrusche che ricordano le rune

vichinghe, anch'esse di origine fenicia. "The Dream of the

Rood" fu dapprima inciso in rune anglosassoni su una croce in

pietra oltre il Vallo di Adriano a Ruthwell, in Scozia, in

seguito in lettere romane su pergamena in un manoscritto

lasciato da un pellegrino a Vercelli, in Italia. Geoffrey

Chaucer, che visitò Firenze nel XIV secolo, ci racconta nei Canterbury

Tales del Re anglosassone pagano Alla del

Northumberland che usa una Bibbia celtica, "Un libro bretone,

con gli Evangeli", correlando questo racconto anche con il

viaggio di Constance in Islam (Man of Law's Tale, II.B.666,

Racconto del Commissario di Giustizia). Prima Wulfila, in

seguito Cirillo e Metodio, idearono alfabeti pressocché nuovi

per tradurre la Bibbia in gotico e slavo. Fedor Dostoevskij,

che scrive L'idiota a Firenze nel XIX secolo, descrive

il suo principesco eroe, durante il viaggio di ritorno in

Russia, attraverso la Svizzera, nell'atto di scrivere in

cirillico la firma dell'abate Paphnutius del XIV secolo, il

cui nome riflette come in uno specchio quello del Padre del

deserto nell'egizia Tebaide. Il nostro alfabeto raggiunse

l'India e la Malesia, arrestandosi improvvisamente in Cina.

Oggi, per le strade di Firenze, nel mercato di San Lorenzo,

immigrati cinesi dipingono in una meravigliosa calligrafia

pittografica, degna di un manoscritto della Biblioteca

Laurenziana, il nostro alfabeto romano così come essi lo hanno

appreso, dove la A può essere una pagoda, la B il bambù, la C

un crostaceo:

While I give to gypsy children in Florence's streets alphabet and number cards:

Io invece dono ai bambini Rom per le strade di Firenze dei cartoncini con l'alfabeto e i numeri:

On one side:

Da un lato l'alfabeto:

A B C E F G

H I J K L M

N O P Q R S T

U V W X Y Z

On the other:

Dall'altro i numeri:

1 . 6 ......

2 .. 7.......

3 ... 8........

4 .... 9.........

5 ..... 10..........

You, too, can define and copy these, six to a page at a time, double-sided, printing them and cutting them, to give to children, any children. But especially children in need of them.

Selezionando e copiando le immagini, sei per ciascuna pagina, per poi stamparle fronte retro e ritagliarle in sei quadrati, si possono creare dei cartoncini da donare ai bambini, a tutti i bambini. In particolare ai bambini bisognevoli.

We chose this theme of the City and the Book because of the presence in the Laurentian Library in Florence of the Codex Amiatinus, the great Anglo-Saxon Bible, which takes two men to lift, brought here to Italy from Wearmouth Jarrow by the Abbot Ceolfrith who died on the journey to Rome carrying it, 716. The Hebrew Bible speaks of two persons within its pages being responsible for the preservation and observation of the Bible as scribal/oral text, the Prophetess Huldah (2 Kings 22.8-23.25, 2 Chronicles 34.14-35-37) and the Prophet Ezra (Nehemiah 8.1-18). The Codex Amiatinus copied Cassiodorus' portrait of the Prophet Ezra. Most Bibles were created in the quiet of monasteries, originally each one a unique manuscript, rather than in the bustle of cities; they were books of the desert, not of the town. Today they are wrenched out of their context of liturgy and lectio divina and placed in museums and libraries in cities, with only scholars allowed access. Dott.ssa Franca Arduini speaks of the need to conserve, restore and, above all, share cultural treasures, such as the Codex Amiatinus, as Ireland has done with her Book of Kells. Jerome and his great friends, Paula and Eustochium, laboured together translating Hebrew and Greek into Latin. Wulfila translated Greek into Gothic. Cyril and Methodius translated Greek into Slavonic. Thanks to my once student, Philip Roughton, I saw the Icelandic manuscripts returned there from Denmark and heard Icelanders telling of that return by their former oppressors who had once forbidden them their own language. Original manuscripts can be published in exact facsimiles and restored in situ to the places of their origins, and they can be published on CD, as has been done with the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Kells, and the Codex Amiatinus. Included in such a collection could be the great Hebrew Bibles, like the Codex Alapensis and the Codex Leningradensis, the great Greek Bibles, like the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Alexandrinus, and Lindisfarne's Barberini Gospels, now in the Vatican, scribed by Bishop Hygebeald, and Canterbury's Codex Aureus, today in Stockholm. Perhaps there could be a boxed set in museum and book and church shops of all these great Bibles, that all who desire may read, women at home teaching children, professors in universities teaching students, the monk or nun in their cell, all sharing in this text. Perhaps UNESCO and the European Community could undertake such a project.

La scelta di questo tema su la città e il libro è stata dettata dal fatto che la Biblioteca Laurenziana a Firenze custodisce il Codex Amiatinus, l'imponente Bibbia anglo-sassone che solo due uomini riescono a sollevare. La Bibbia fu portata qui in Italia da Wearmouth Jarrow dall'abate Ceolfrith, che la morte colse nel 716 proprio durante questo suo viaggio per trasportarla a Roma. Tra le pagine della Bibbia ebraica a due figure è affidato il compito della conservazione e dell'osservanza della Bibbia come testo scritto/orale, alla Profetessa Culda (cf. 2 Re 22 8-23; 25, 2 Cronache 34 14-35-37) e al Profeta Esdra (cf. Neemia 8 1-18). Il Codex Amiatinus ricopiò il ritratto del Profeta Esdra di Cassiodoro. La maggior parte delle Bibbie furono approntate nella quiete dei monasteri - in origine ciascuna Bibbia era un manoscritto unico - e non nel trambusto della città. Le Bibbie erano libri del deserto, non della città. Oggi questi manoscritti strappati dal loro contesto, quello della liturgia e della lectio divina sono collocati nei musei e nelle biblioteche cittadine, resi accessibili soltanto agli studiosi. La Dott.ssa Franca Arduini sottolinea quanto sia necessario conservare, restaurare e, soprattutto, condividere i tesori culturali, quali il Codex Amiatinus, nel modo in cui l'Irlanda ha fatto con il suo Book of Kells. Girolamo e le sue grandi amiche, Paola ed Eustochio, profusero grandi energie per tradurre l'ebraico e il greco della Bibbia in latino. Wulfila tradusse il greco in gotico. Cirillo e Metodio tradussero il greco in slavo. Grazie a Philip Roughton, mio ex allievo, ho potuto vedere i manoscritti islandesi riportati dalla Danimarca, ed ho ascoltato degli islandesi raccontare della restituzione di quei manoscritti da parte degli oppressori di un tempo, che avevano loro proibito l'uso della propria lingua. I manoscritti originali potrebbero essere pubblicati in edizioni in facsimile rigorosamente fedeli e così restituiti ai luoghi d'origine per essere custoditi in situ. Potrebbero anche essere pubblicati su CD, così come è stato fatto con i Lindisfarne Gospels, il Book of Kells, ed il Codex Amiatinus. In questa collezione si potrebbero includere le grandi Bibbie ebraiche, come il Codex Aliapensis ed il Codex Leningradensis, le grandi Bibbie greche come il Codex Sinaiticus ed il Codex Alexandrinus, i Barberini Gospels di Lindisfarne, attualmente custoditi in Vaticano, redatti dal vescovo Hygebeald, ed il Codex Aureus di Canterbury, oggi a Stoccolma. Un cofanetto in più volumi potrebbe raccogliere tutte queste grandi Bibbie, perché sia consultabile e disponbile nei musei, nelle librerie, nelle librerie ecclesiastiche. Volumi disponibili per la lettura da parte di tutti coloro che lo desiderino, dalle donne a casa per insegnare ai bambini, dai professori nelle università, dal monaco o dalla monaca nella loro cella, tutti così condividendo il testo della Bibbia. Forse l'UNESCO e l'Unione Europea potrebbero intraprendere questo progetto.

Hebrew, Irish and Anglo-Saxon Bibles repeat the 'carpet pages' of Muslim Korans, as in the Codex Propetarum Cairensis, the Codex Leningradensis, the Lindisfarne Gospels and The Book of Kells. The Irish Christian monks found on the Ultima Thule of Iceland by its pagan Viking settlers possessed books (Psalters, Bibles), bells, and staffs. Muslims treasured the Koran and the prayer carpet. The shape of a parchment page and the shape of a carpet are both oblong, dictated by the exigencies of skin size and of loom. It is possible in these essays to search references to 'carpet' to find these pages. Hebrew Bibles, when worn from use and damaged, are given burial in the earth or entombment with a revered Rabbi. Similarly Christian saints could be buried with their Gospels, as was St Cuthbert on Lindisfarne with the Stoneyhurst Gospel.) The few Hebrew Bibles that survive from the first millennium number an important cluster, now in St Petersburg, of Near Eastern texts found in the Crimea, where Saints Cyril and Methodius had journeyed to study Hebrew, before their formulating the Glagolitic/Cyrillic alphabet for Slavic peoples. Again, these cross-references to the Crimea are hyper-linked.

Le Bibbie ebraiche, irlandesi e anglo-sassoni ripetono "le pagine tappeto" dei Corani musulmani, così come nel Codex Prophetarum Cairensis, nel Codex Leningradensis, nei Lindisfarne Gospels e nel Book of Kells. I monaci irlandesi, tracce della cui presenza furono scoperte nell'Ultima Thule dell'Islanda dai pagani vichinghi che vi si insediarono, possedevano libri (Salteri, Bibbie), campane, e bordoni. I musulmani avevano caro il Corano e il tappeto della preghiera. La forma obluna di un pagina in pergamena e quella di un tappeto sono obbligatoriamente dettate dalle dimensioni della pelle e da quelle del telaio. Nei saggi qui presentati è possibile rintracciare i rimandi ipertestuali alle pagine tappeto. Le Bibbie ebraiche, quando logore per l'uso e danneggiate vengono sepolte nella terra o inumate assieme ad un venerato Rabbino. Parimenti i santi cristiani potevano essere sepolti con i loro Vangeli, così come è avvenuto per san Cuthbert sull'isola di Lindisfarne con i Stoneyhurst Gospels. Le poche Bibbie ebraiche superstiti risalenti al primo millennio annoverano una importante raccolta di testi del Vicino Oriente ritrovati in Crimea (ora a San Pietroburgo), dove, prima di formulare l'alfabeto glagolitico e cirillico per i popoli slavi, i santi Cirillo e Metodio avevano compiuto un viaggio per lo studio dell'ebraico. Anche in questo caso i rimandi alla Crimea sono correlati ad altre pagine Web tramite link ipertestuali.

The codices of Bible and Koran were a technological development for greater ease in reading and cross-referencing than are the scrolls of the Torah, to both of which were added vowel signs for greater ease in reading Hebrew and Arabic consonants. The alphabet and the Bible, the narration of a People in time and space, were but early forms of the computer, with which all European nations then sought to hyperlink. Book cupboards in Ravenna, in Vivarium, in Northumbria, shrines and satchels for books in Ireland, exquisite bindings of Bibles and Gospels both East and West, echo the Ark of the Torah. The Ruthwell Cross and the Codex Amiatinus Ezra illumination show the Bible's holiness, Christ holding the Gospel with liturgical veil, the Bible cupboard shown as Ark, Ezra as High Priest. In art two birds can symbolize the Cherubim on either side of the Ark. In the gable of the Codex Amiatinus' book cupboard are two such birds flanking a sacred recess, below them oxen, which we can see in the enlargement of that page, placing the newest technology at the service of the oldest. (One visualizes Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrith and their library-travelling across Europe with a lumbering ox cart drawn by such oxen.) The alphabet and the Bible, as it were, conveying Hammurabi's Laws from Babylon in Iraq through the migrating Hebrews, in Egyptian bondage and in Israel, in Babylonian exile and in Jerusalem, became a palimpsest that taught all Europe religion, law, civilization, history, reaching beyond Italy, France, Germany, Spain , to Ireland , and the British Isles , Russia , Scandinavia, and its Ultima Thule of Iceland , and even Vinland; in each instance initially with a tremendous burst of creative energy, as the new culture was adopted, usually through the active involvement and mediation of women remembering their Gospel presence (Matthew 26.12-13, 27.55-61, 28.1-10, Mark 14.9, 15.40-41,47, 16.1-8, Luke 7.44-8.3, 23.55, 24.1-11,24, John 11.2, 20.1-18, etc.).

Rispetto ai rotoli della Torah i codici della Bibbia e del Corano furono un progresso tecnologico che facilitò enormemente la lettura e i rinvii. Sia alla Bibbia sia al Corano furono aggiunti i segni delle vocali per facilitare la lettura delle consonanti e dell'ebraico e dell'arabo. L'alfabeto e la Bibbia, la narrazione di un popolo nel tempo e nello spazio, non furono altro che prototipi del computer, tramite cui tutte le nazioni europee cercarono di creare dei link. Gli armadi per libri a Ravenna, a Vivarium, in Nortumbria, le teche e le sacche per libri in Irlanda, le raffinate rilegature di Bibbie e Vangeli, orientali ed occidentali, echeggiano l'Arca della Torah. La Ruthwell Cross e la miniatura di Esdra del Codex Amiatinus attestano la sacralità della Bibbia, Cristo che tiene il Vangelo con il velo liturgico, l'armadio della Bibbia come Arca, Esdra effiggiato come Sommo sacerdote. Nell'arte due uccelli possono simboleggiare il cherubino posto su entrambi i lati dell'Arca. Nel timpano dell'armarium per libri del Codex Amiatinus due uccelli affini fiancheggiano un sacro recesso, sotto questi, tramite un ingrandimento della pagina - ponendo la nuova tecnologia al servizio della più antica - osserviamo dei buoi. Scorgiamo Benedict Biscop e Ceolfrith, e la loro biblioteca itinerante che attraversò tutta l'Europa con un fragoroso carro trainato da tali buoi. L'alfabeto e la Bibbia, trasmettendo, così per dire, le Leggi di Hammurabi da Babilonia in Irak con la diaspora degli ebrei, nella schiavitù d'Egitto e in Israele, nell'esilio babilonese e in Gerusalemme, divennero un palinsesto che insegnò a tutta l'Europa la religione, la legge, la civiltà, la storia, raggiungendo al di là dell'Italia, la Francia, la Germania, la Spagna, fino ad arrivare in Irlanda e nelle Isole britanniche, in Russia, in Scandinavia, e sino alla sua ultima Thule, l'Islanda, persino nel Vinland. In ogni caso, inizialmente, con una straordinaria esplosione di energia creativa nell'adottare la nuova cultura, in genere per la partecipazione attiva e la mediazione delle donne che ricorda la presenza femminile nel Vangelo (Mt 26.12-13, 27.55-61, 28.1-10, Mc 14.9, 15.40-41, 47, 16.1-8, Lc 7.44-8.3, 23.55, 24.1-11,24, Gv 11.2, 20.1-18, ecc.).

We design this text making partial use of the INSULAR SCRIPT of the Book of Kells in Ireland, which was to influence, by way of Charlemagne's Alcuin from York, the beautiful Bolognan libraria script in which Dante's codices are typically written - and in which modern books, and even websites, are typeset. While our CAPITALS go back to inscriptions sculpted on stone triumphal arches in Rome and forward to preaching crosses in Scotland. Where possible we give you the text of the manuscript, for instance, the Codex Amiatinus, which, though usually copying the rounded uncials of Cassiodorus' now mostly lost Italian Codex Grandior (U,V=U), here is copying ROMAN CAPITALS (U,V=V), reflecting inscriptions in stone in ancient Rome, as do the Latin letters on Ceolfrith's dedication stone of St Paul's at Jarrow, and the Latin letters on the stone of the Ruthwell Cross.

Componiamo questo testo in parte utilizzando la SCRITTURA INSULARE del Book of Kells in Irlanda, che tramite la corte di Carlo Magno influenzerà Alcuino da York, e la bella scrittura libraria Bolognese nella quale sono in genere vergati i codici di Dante - e nella quale sono composti i libri moderni, e perfino i siti Web. Le nostre CAPITALI, invece, si rifanno alle iscrizioni scolpite sugli archi trionfali in pietra a Roma, e in epoca più tarda alle croci-sermone in Scozia. Laddove è possibile diamo il testo del manoscritto, ad esempio, il Codex Amiatinus, che, benché in genere riproduca l'onciale arrotondato (U,V=U) del codice italiano Codex Grandior di Cassiodoro, per la maggior parte andato perduto, qui riproduce le CAPITALI ROMANE (U,V=V), che riflettono le iscrizioni su pietra nell'antica Roma, così come le lettere latine dell'epigrafe dedicatoria di Ceolfrith della Cattedrale di St Paul a Jarrow, e le lettere latine sulla pietra della Ruthwell Cross.

Ceolfrith would have seen Roman triumphal arches. He may also be responsible for the Ruthwell Cross.

Ceolfrith deve aver visto gli archi trionfali romani. E' presumibilmente da attribuire a lui anche la Ruthwell Cross.

Likewise we make use of the early alternating red and green capitals to manuscript texts, which reflect as well Dante's poetic garb for Beatrice in the Purgatorio and which have become the colours of the Italian flag. Next year our colours shall be the alternatings reds and blues of the later medieval manuscripts. Ezra re-wrote the destroyed Bible at great speed, in shorthand, and so the Codex Amiatinus miniature shows him writing Tyronian notes, shorthand , named for Cicero's slave Tyro who took down his master's speeches in abbreviated phonetic code, in so doing the miniature mirroring what was done in Jerusalem and in Vivarium, in Wearmouth and in Jarrow, the restoration from destruction of the Bible. We present these papers bilingually, like a Rossetta stone, so they may be of use across languages, even an aid to learning each other's language, in a translatio studii.

Parimenti utilizziamo le capitali rosse e verdi alternate degli antichi testi manoscritti, colori che riflettono anche la veste poetica di Beatrice nel Purgatorio, divenuti poi i colori della bandiera italiana. Il prossimo anno i nostri colori saranno il rosso e il blu alternati dei manoscritti di epoca più tarda. Esdra riscrisse prontamente in tachigrafia la Bibbia andata distrutta, e dunque la miniatura del Codex Amiatinus lo raffigura intento a scrivere in note tironiane. Quest'ultima espressione deriva dal nome dello schiavo di Cicerone, Tiro, che trascriveva i discorsi del padrone utilizzando un codice fonetico abbreviato. La miniatura rispecchia, dunque, ciò che veniva fatto a Gerusalemme e a Vivarium, a Wearmouth e a Jarrow. Vale a dire preservare la Bibbia. Presentiamo questi interventi in forma bilingue, come una stele di Rosetta, perché possano essere utili nel passaggio da una lingua all'altra, e perché siano anche un sostegno nell'apprendere gli uni la lingua degli altri, in una translatio studii.

Monasticism ideally combines prayer, study, work, and formerly included the entire making and copying of codices, even the farming of cattle providing both parchment and food. Therefore, we asked Brody Neuenschwander (scribe of Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books) to lead a workshop on the making of medieval codices at Monte Amiata and we invited James Pepper , Bible scribe, to come, both, young Americans. Above all, we asked librarians and scholars from Florence's Laurentian Library, dott.ssa Franca Arduini , England's British Library, Dr Scot McKendrick , Ireland's Trinity College Library, Dr Bernard Meehan , and Iceland's Stofnun Arni Magnusson, Professor Svanhildur Oskarsdottir , to participate, telling us, as the Keepers of these Manuscripts, of the Codex Amiatinus, the Codex Sinaiticus, the Book of Kells, and the Codex Stjorn. The congress's theme is thus alphabet and codicology, the complete study of the book, in particular Psalter and Bible, the latter so often laid, liturgically, upon the altar, and of their travels, in scripts and satchels of monks and pilgrims from one end of Europe to the other, shaping our civilization. Gospels on altars and books in scrips and satchels are for this reason hyperlinked.Idealmente il monachesimo coniuga preghiera, studio, lavoro, e in passato comportava anche l'allestimento e la copiatura dei codici, persino l'allevamento del bestiame che forniva pergamena e cibo. Abbiamo, pertanto, invitato Brody Neuenschwander (calligrafo dei Prospero's Books di Peter Greenaway) per un workshop sulla realizzazione dei codici medievali. Il laboratorio si terrà presso l'Abbazia di San Salvatore sul Monte Amiata. E' stato anche invitato James Pepper, calligrafo della Bibbia. Ambedue sono giovani americani. Al convegno sono stati invitati bibliotecari e studiosi, per parlare, in particolare, del Codex Amiatinus, del Codex Sinaiticus, del Book of Kells, e del Codex Stjorn. La dott.ssa Franca Arduini della Biblioteca Laurenziana di Firenze, il Dr Scot Mckendrick della British Library, il Dr Bernard Meehan della Trinity College Library, il Professor Svanhildur Oskarsdottir dello Stofnun Arni Magnusson, Islanda. Tutti conservatori di questi manoscritti. Il tema del convegno è, dunque l'alfabeto e la codicologia, lo studio completo del libro, del Salterio e della Bibbia, in particolare - quest'ultima così spesso posta sull'altare con funzione liturgica - della consuetudine dei monaci e dei pellegrini di portare con sé in viaggio da un capo all'altro dell'Europa questi libri nelle bisacce e nelle sacche, lasciando così una profonda impronta nella nostra civilizzazione. A motivo di ciò sono stati creati dei link ipertestuali ogni qual volta si faccia riferimento ai Vangeli posti sugli altari e ai libri che i monaci portavano con sé nelle bisacce e nelle sacche.

We discuss the Hebrew Bible and the Christian one, in Greek , Latin , Gothic , Irish , Old English , Icelandic , Old Church Slavonic , Mozarabic . Origen studied the Hebrew and Greek Bibles (†254). Jerome, with the aid of Paula and Eustochium, translated the Hebrew and Greek Bibles into the Latin Vulgate (387-393). Slightly earlier than Jerome, the Goth bishop Wulfila (311-383) had adapted the alphabet to transcribe that now-lost Gothic language and translated the Gospel into it. Cassiodorus (†583) set in motion again the desire for a correct Bible, creating his great pandect, the Codex Grandior, as well as his Novem Codices, and at the same period Wulfila's Gothic Bible was again written out in the Codex Argenteus, inagold and silveraupon purple parchment, both Bibles associated with the court of the Gothic Arian Emperor Theodoric of Ravenna. At that moment of great renewal for the Bible in Europe was also the birth of the Koran with Mohammad (570-632). Bishop St Frediano from Ulster, perhaps St Finnian (†579), having converted Tuscan Lucca to Christianity, returned to Ireland with a Bible from Rome. Anglo-Saxon monks bought up Cassiodorus' abandoned library, bringing it to Northumbria (679-680). Then Abbot Ceolfrith trudged from Wearmouth Jarrow, dying on the journey (†716), bringing the Codex Amiatinus, which may have been scribed in part by Bede, to Rome, which partly copies Cassiodorius' pandect, the Codex Grandior, that they had acquired. Saints Donatus, Andrew and Bridget around 850 came from Ireland to convert the region about Fiesole. In their day Vikings were marauding insular monasteries, Iona and Lindisfarne, burning their books. In 868 Cyril and Methodius were honoured in Rome with liturgies in Slavonic. In 987 King Vladimir converted Kievan Rus to Orthodox Christianity. In 1000, Iceland's Althing decreed that Viking Icelanders be Christian. Icelandic scholar priests studied at St Victor in Paris and at Lincoln in England. Saint Andrew of Ireland's cell was taken over by Saint Bernardino of Florence. Indeed, the Tuscan love for hermitages and places of retreat for prayer may well be inherited from the practice of Irish pilgrim hermits to these parts, Psalter and Gospel in hand, their descendants the monks of Vallombrosa, the friars of Monte Senario. Thus, we see Bible-carrying pilgrim scholars going out from the centres of Jerusalem and Rome, then returning from the margins, from the periphery, to re-convert the centre, to re-fresh and re-correct the Bible with their great learning and their boundless energy. Finally, we see the commentary by Beatus of Liebana to the Apocalypse re-convert Spain from Islam to Christendom, yet using the riches of Islamic culture in its imagery. We give a time line and a map, this last explicitly showing the pilgrimages women made across the face of Europe, prompted by the Bible and the saints.

Tratteremo della Bibbia ebraica e della Bibbia cristiana, in greco, latino, gotico, irlandese, inglese antico, islandese, nelle antiche lingue slave della chiesa, e anche della Bibbia mozarabica (che risentì dell'influenza islamica). Origene studiò le Bibbie greche ed ebraiche (†254). Girolamo, con l'aiuto di Paola ed Eustochio, tradusse le Bibbie ebraiche e greche nella vulgata latina (387-393). Un po' prima di Girolamo, il vescovo gotico Wulfila (311-383) aveva adattato l'alfabeto per trascrivere quella lingua gotica ormai perduta, e in questa lingua aveva tradotto il Vangelo. Fu ancora Cassiodoro (†583), assecondando il suo desiderio di avere una Bibbia corretta ad approntare la grande pandette, il Codex Grandior, ed il Novem Codices. Nello stesso periodo la Bibbia gotica di Wulfila fu riscritta nel Codex Argenteus, utilizzando inchiostro oro e argento su pergamena porpora, entrambe le Bibbie sono strettamente legate alla corte dell'imperatore gotico ariano Teodorico di Ravenna. In quel momento di grande rinascita della Bibbia in Europa nasce con Maometto anche (570-632) il Corano. Il vescovo san Frediano dell'Ulster, forse San Finnian (†579), avendo convertito la toscana Lucca alla cristianità, fece ritorno in Irlanda portando con sé una Bibbia da Roma. Monaci anglosassoni acquisirono la biblioteca abbandonata di Cassiodoro, portandola in Northumbria (679-680). Successivamente l'abate Ceolfrith in cammino da Wearmouth Jarrow alla volta di Roma per portare il Codex Amiatinus muore durante il viaggio (†716). Presumibilmente, il codice fu redatto in parte da Beda, e copiava in parte la pandette di Cassiodoro, il Codex Grandior, che essi avevano acquisito. I santi Donato, Andrea e Brigida intorno all'850 giunsero dall'Irlanda per convertire l'area intorno a Fiesole. All'epoca i vichinghi predavano i monasteri insulari, come Iona e Lindisfarne, bruciando i loro libri. Nell'868 Cirillo e Metodio erano venerati a Roma con liturgie in slavo. Nel 987 il Re Vladimir convertì Kievan Rus all'ortodossia cristiana. Nel Mille l'Althing, l'assemblea nazionale, decretò che gli islandesi vichinghi si convertissero, divenendo, dunque, cristiani. Preti islandesi, compivano i loro studi a San Vittore a Parigi e a Lincoln in Inghilterra. La cella di sant'Andrea d'Irlanda divenne poi la cella di San Bernardino di Firenze. Invero, l'amore toscano per gli eremitaggi ed i luoghi di ritiro per la preghiera può ben essere retaggio della consuetudine dei pellegrini irlandesi di stabilirsi come eremiti in questi luoghi, con Salterio e Vangelo sempre in mano. Loro discendenti sono i monaci di Vallombrosa, i frati del Monte Senario. Incontriamo, dunque, studiosi pellegrini che portano con sé la Bibbia, si recano lontano dai centri di Gerusalemme e Roma, ritornando poi dai margini e dalla periferia per riconvertire il centro, facendo rifiorire e ancora correggendo la Bibbia con la loro grande erudizione e infinita energia. Vediamo, infine, il commento all'Apocalisse del Beatus di Liebana riconvertire la Spagna dall'Islam alla cristianità, tuttavia, ricorrendo alla ricchezza delle immagini della cultura islamica. Viene data una sintesi cronologica e una mappa. Quest'ultima mostra chiaramente i pellegrinaggi che le donne compirono in tutta Europa, ispirati in questo dalla Bibbia e dai Santi.

Though this conference was specifically on the Codex Amiatinus there are aspects of it that were not mentioned in the various papers. If one takes up the historical writings of Bede one finds in the History of the Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow Benedict Biscop sending to France for glaziers for the windows of St Peter's Church at Wearmouth, who went on to make lamps and vessels and whose handicraft can be seen in the glass ink bottles in the Codex Amiatinus Ezra portrait. (Paul Meyvaert tells us in his Speculum article that Bede came to correct his earlier perception of Ezra as High Priest, the Codex Amiatinus mistakenly showing him with the Urim and Thummim and phylacteries of that sacred office). While the Ecclesiastical History of the English People gives Abbot Ceolfrith of Wearmouth and Jarrow's lengthy and classically-styled letter (actually written by Bede) in 710 to King Nechtan of the Picts, accompanying church builders in stone the abbot sent the king, about the Roman dating of Easter and the Roman tonsure. Stone sculpture of the inhabited vine at Jarrow is mirrored in the distant stone crosses of Bewcastle and Ruthwell in the Pictish region about Hadrian's Wall. Likewise, the Ruthwell Cross's Bible in stone mirrors the monastery churches of St Peter's at Wearmouth and St Paul's at Jarrow, whose south walls had scenes from the Gospels, whose north walls were of John's Apocalypse. Bede's Ecclesiastical History demonstrates Jarrow's shared knowledge of Hilda's Whitby, Cuthbert's Lindisfarne. Adamnam's Iona, all of which may provide elements of the Ruthwell Cross and its 'Dream of the Rood', inscribed upon it in runes deriving from Phoenician letters. It may be to Ceolfrith in 710 that we owe the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Crosses and the earliest surviving poem in the English language.

Benché questo convegno fosse incentrato primariamente sul Codex Amiatinus vi sono aspetti di questo codice di cui non si è fatta alcuna menzione nei vari contributi. Prendendo in considerazione gli scritti storici di Beda nella History of the Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow sappiamo che Benedict Biscop fece giungere dalla Francia maestri vetrai per realizzare le vetrate della St Peter Church a Wearmouth, successivamente quegli stessi artigiani continuarono a prestare la loro opera creando lampade e vasi. La loro maestria può essere osservata nei calamai di vetro che compaiono nel ritratto di Esdra del Codex Amiatinus. (Paul Meyvaert nel suo articolo nello Speculum afferma che Beda giunse poi a correggere la sua precedente percezione di Esdra come Sommo Sacerdote, il Codex Amiatinus erroneamente lo mostra con gli Urim, i Tummim e i filatteri di quel sacro ufficio). La Ecclesiastical History of the English People riporta la lunga lettera in stile classico del 710 sulla questione della datazione romana della Pasqua e della chierica romana: la lettera dell'Abate Ceolfrith di Wearmouth e Jarrow (in realtà stilata da Beda) al Re Nechtan dei Pitti, che i costruttori di "chiese in pietra" inviati al Re dall'Abate portarono con sé. La scultura in pietra della vite abitata a Jarrow è riflessa nelle lontane croci in pietra di Bewscastle e Ruthwell, nella regione dei Pitti, intorno al Vallo di Adriano. Analogamente, la Bibbia in pietra della Ruthwell Cross rispecchia le chiese monastiche di St Peter a Wearmouth, e St Paul a Jarrow, le cui pareti sud recavano episodi tratti dai Vangeli, e quelle a nord scene dall'Apocalisse di Giovanni. L'Ecclesiastical History di Beda attesta la reciproca conoscenza tra Jarrow e Whitby di Hilda, Lindisfarne di Cuthbert, e Iona di Adamnam, le quali tutte forniscono elementi presenti nella Ruthwell Cross e nel suo "Dream of the Rood" inciso in rune derivanti dalle lettere fenice. Si deve verosimilmente a Ceolfrith, nel 710, se possediamo la Ruthwell Cross e la Bewcastle Cross, ed il più antico carme esistente in lingua inglese.

Ceolfrith had accompanied Benedict Biscop on one of his many pilgrimages to Rome, in 679-680, bringing back the Codex Grandior, then attempted to return there in 716. Bede says, that while doubling the number of books in both libraries, Ceolfrith ' ita ut tres pandectes nouae translationis, ad unum uetustae translationis quem de Roma adtulerat, ipse super adiungeret, quorum unum senex Romam rediens secum inter alia pro munere sumpsit, duos utrique monasterio reliquit' [' added three copies of the new translation of the Bible to the one copy of the old translation which he had brought back from Rome. One of these he took with him as a present when he went back to Rome in his old age, and the other two he bequeathed to his monasteries ' (Historia abbatum 15, pp. 379-380)]. That gift is our Florentine Codex Amiatinus, an insurance copy which has survived for us in its entirety. Both Wearmouth's St Peter's and Jarrow's St Paul's abbey churches, the Historium abbatum auctore anonymo notes, had a pandect placed in them: ' quorum duo per totidem sua monasteria posuit in aecclesiis'. We see similar ecclesiatical and liturgical use made of the Lichfield Gospels and of Byzantino-Slavic Bibles as placed on altars. Likely the partial exemplar, Cassiodorus' Codex Grandior, and the Wearmouth and Jarrow sister copies, apart from fragments, were lost in Viking raids and subsequent depradations. Martin McNamara in print notes the closeness of the Psalter section of the Codex Amiatinus to the Irish Hebraicum Psalter, even to its using the St Columba series of psalm headings in a form only paralleled in the Cathach and the Irish per-symbol (SEMPER), not copied elsewhere in the codex (Martin McNamara, The Psalms in the Early Irish Church, p. 105). Ceolfrith himself, Bede tells us, demanded that the entire Psalter be recited twice each day. Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon monasticism, for all its Rome-emulation, was rooted in Irish learning and in Irish monasticism, which in turn had sought the closest translations into Latin from the Hebrew and the Greek for use in the liturgy, and thus Wearmouth-Jarrow and Lindisfarne-Iona came to combine the best of Celtic and Roman practices.Nel 679-680 Ceolfrith aveva accompagnato Benedict Biscop in uno dei suoi molti pellegrinaggi alla volta di Roma per riportare il Codex Grandior, in seguito, nel 716, tentò di ritornarci. Afferma Beda che mentre il numero dei libri raddoppiava in tutt'e due le biblioteche, Ceolfrith 'ita ut tres pandectes nouae translationis, ad unum uetustae translationis quem de Roma adtulerat, ipse super adiungeret, quorum unum senex Romam rediens secum inter alia pro munere sumpsit, duos utrique monasterio reliquit' ['aggiungeva tre copie della nuova traduzione della Bibbia all'unica copia della vecchia traduzione che aveva riportato da Roma. Una di queste copie la portò con sé come dono, quando in vecchiaia ritornò a Roma le altre due le lasciò in eredità ai suoi monasteri' (Historia abbatum 15, pp. 379-380)]. Tale dono è il nostro fiorentino Codex Amiatinus, una copia di riserva che ci è pervenuta nella sua interezza. Sia l'abbazia di St Peter a Wearmouth sia quella di St Paul a Jarrow, così come l'Historium abbatum auctore anonymo registra, avevano una pandette: "quorum duo per totidem sua monasteria posuit in aecclesiis". Un uso ecclesiastico e liturgico analogo lo osserviamo per i Lichfield Gospels e delle Bibbie bizantino-slave, poste sugli altari. Verosimilmente, l'esemplare parziale, il Codex Grandior di Cassiodoro, e le copie gemelle di Wearmouth e Jarrow, a parte dei frammenti, andarono perduti nel corso di incursioni vichinghe e a causa delle spoliazioni che ne seguirono. La pubblicazione di Martin McNamara rileva la contiguità della sezione del Salterio del Codex Amiatinus e dell'irlandese Hebraicum Psalter, anche nel suo uso della serie di capitolazioni dei salmi di San Colombano in una forma eguagliata unicamente nel Cathach e nell'uso della nota tironiana irlandese per (SEMPER), non trascritta altrove nel codice (Martin McNamara, The Psalms in the Early Irish Church, p. 105). Ceolfrith stesso, ci dice Beda, esigeva che l'intero Salterio fosse recitato due volte al giorno. Il monachesimo anglo-sassone Northumbro, nella sua emulazione di Roma, era radicato nella cultura irlandese e nel monachesimo irlandese, che a sua volta aveva cercato le traduzioni in latino più fedeli dall'ebraico e dal greco, affinché fossero usate nella liturgia. Wearmouth-Jarrow e Lindisfarne-Iona arrivarono, dunque, a combinare i migliori riti celtici e romani.

In dedicating this conference to Fioretta Mazzei , we call to mind the need not only to study the Bible, the Gospel, but to live it, writing its words not on stone but in our living flesh. Fioretta Mazzei and Giorgio La Pira worked together with the Repubblica di San Procolo and its Messa dei Poveri, its Mass for the Poor, inviting all those rejected by our society, our culture, the poor, the homeless, the refugee, the immigrant, the handicapped, the one lacking work. Bruno Vivoli of the Repubblica di San Procolo engraved the figure of Dante teaching the Commedia to Florence that we use on our programmes. We held the inauguration of the Conference in the Sala dei Cinquecento, to which Giorgio La Pira and Fioretta Mazzei had invited all the world leaders to sign the Declaration of Peace, and where in the thirteenth century the five hundred leading members of the Arti or Guilds would meet to govern the Republic of Florence, ' nell'amore di Dio e del prossimo', 'in the love of God and neighbour', before the Medici appeared in civic documents. Fioretta worked tirelessly for peace, for the Gospel, for Florence, for women, for children, and for friendship between Jew and Christian. The Repubblica di San Procolo, the wedding feast of the Gospels' parables, could come to the Congress at the Palazzo Vecchio, at the Certosa. I first met her the year before she died, at the Messa dei Poveri in the Badia Fiorentina, by chance (but Julian of Norwich in the Showing of Love says with God nothing is ever by chance), and in that glorious day Fioretta invited this then-still Anglican hermit to lunch in her book-filled home in the San Frediano district of Florence, and to supper in a Florentine garden with the Amicizia Ebraico-Cristiana.

Nel dedicare questo convegno a Fioretta Mazzei, richiamiamo alla memoria non soltanto il bisogno di studiare la Bibbia e il Vangelo, ma di viverli, incidendo le loro parole non sulla pietra ma nella nostra viva carne. Fioretta Mazzei e Giorgio La Pira con la Repubblica di San Procolo e la sua Messa dei Poveri hanno accolto tutti coloro che la nostra società e cultura rifiutano e respingono ai margini: i poveri, i senza tetto, i rifugiati, gli immigrati, gli handicappati, chi non ha un lavoro. E' di Bruno Vivoli della Repubblica di San Procolo l'incisione di Dante che insegna la Commedia a Firenze utilizzata come logo nei programmi del convegno. L'inagurazione si è svolta nel Salone dei Cinquecento, dove Giorgio La Pira e Fioretta Mazzei hanno invitato tutti i leader del mondo a firmare la Dichiarazione di Pace, e dove nel XIII secolo i cinquecento membri guida delle corporazioni delle Arti o Mestieri si radunavano per governare la Repubblica di Firenze "nell'amore di Dio e del prossimo", prima che i Medici comparissero nei documenti civici. Fioretta ha instancabilmente lavorato per la pace, per il Vangelo, per Firenze, per le donne, per i bambini, per l'amicizia ebraico cristiana. La Repubblica di San Procolo, il banchetto nuziale delle parabole dei Vangeli ha potuto essere presente al Convegno in Palazzo Vecchio, e poi alla Certosa. Ho conosciuto Fioretta, e per puro caso, alla Messa dei Poveri alla Badia Fiorentina, solo un anno prima della sua morte. Quel magnifico giorno invitò a pranzo questa povera eremita, allora ancora anglicana, nella sua casa piena di libri nel quartiere fiorentino di San Frediano, e poi a cena in un giardino fiorentino in occasione di un incontro dell'Amicizia Ebraico-Cristiana.

Giannozzo Pucci has been in quest for the 'secret of the Renaissance'. As a medievalist, pouring over thirteenth and fourteenth century documents in Florentine archives and manuscripts in Florentine libraries, I came to see the Renaissance as born long before the Medici, as arising from Florence's identification not with Athens, but Jerusalem, and, from her littleness, with David's Bethlehem, with Mary's Nazareth. Orsanmichele, in the thirteenth century, was established to feed even the enemy in time of famine, to atone for Florence's sanctions against Pisa causing Ugolino's cannibalism of his own progeny. Meeting Fioretta Mazzei, Giannozzo Pucci, don Corso Guicciardini, all engaged with helping others, I learned that here was Florence's secret, in the love of God and neighbour, 'nell'amore di Dio e del prossimo', the receiving of abandoned babies at the Bigallo by the Duomo and at the Ospedale degli Innocenti by the Santissima Annunziata, the feeding of the hungry by the Confraternity of the Madonnina del Grappa, likewise in the Piazza Santissima Annunziata, the assisting of the proud poor by the Buonuomini of San Martino by the Badia, the caring for the ill and the dying by the Arciconfraternita della Misericordia by the Duomo, and now, joining these confraternities from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Giorgio La Pira and Fioretta Mazzei's Messa dei Poveri of the Repubblica di San Procolo in the Badia where Boccaccio lectured on Dante's Commedia . Even the Medici's patron, St Lawrence, when asked to give up Rome's ecclesiastical treasures, presented the barbarian invaders with Rome's poor. Professor Regina Schwartz in her book The Curse of Cain has spoken of the Bible's legacy of violence and racism. Simone Weil observed of the Iliad,

But nothing of all that the people of Europe have produced is worth the first known poem to have appeared among them. Perhaps they will rediscover that epic genius when they learn how to accept the fact that nothing is sheltered from fate, how never to admire might, or hate the enemy, or to despise sufferers. It is doubtful if this will happen soon.Europe neither invented the alphabet nor produced the Bible nor its Gospel. But instead, like Mary, where she has taken this to heart as Magnificat, has done magnificently. Florence, in art and in life, preaches and practices the Gospel, the Bible, being strong through caring for the weak, reversing hierarchies. Look about you. The Golden Doors of the Baptistry, the David once of the Palazzo del Popolo, the Pieta once of the Duomo, the Fra Angelicos of San Marco, the Della Robbias everywhere, on Orsanmichele, in the Duomo, on the spandrels of the Ospedale degli Innocenti . . .

Ospedale degli Innocenti, where Fioretta Mazzei held

the conference that drafted the

U.N. Rights of the Child

Giannozzo Pucci ha ricercato il "segreto del Rinascimento". Come medievista, lavorando intensamente sui documenti del XIII e del XIV secolo custoditi negli archivi fiorentini, e sui manoscritti conservati nelle biblioteche fiorentine, sono giunta alla conclusione che la nascita del Rinascimento va collocata molto tempo prima dei Medici, essendo originata non dall'identificazione di Firenze con Atene, ma con Gerusalemme, e, a motivo della sua piccolezza, con la Betlemme di Davidc e con la Nazareth di Maria. Orsanmichele fu edificata nel XIII secolo per sfamare persino i nemici in tempo di carestia e riparare alle sanzioni di Firenze contro Pisa, causa del cannibalismo di Ugolino. Avendo conosciuto Fioretta Mazzei, Giannozzo Pucci, don Corso Guicciardini e la loro dedizione agli altri, ho appreso che in questo consiste il segreto di Firenze: "nell'amore di Dio e del prossimo": l'accoglimento dei bambini abbandonati al Bigallo - a pochi passi dal Duomo - allo Spedale degli Innocenti, a pochi passi dalla Santissima Annunziata, il dar da mangiare agli affamati da parte dell'Opera della Divina Provvidenza Madonnina del Grappa, anch'essa in Piazza Santissima Annunziata, l'assistenza dei "vergognosi poveri" dalla Compagnia dei Buonomini di San Martino, nelle immediate adiacenze della Badia, l'assistenza degli infermi e dei morenti ad opera della Arciconfraternita della Misericordia, a pochi passi dal Duomo, ed ora, unendosi a queste confraternite del Medioevo e del Rinascimento, la Messa dei Poveri di Giorgio La Pira e Fioretta Mazzei della Repubblica di San Procolo alla Badia, dove Boccaccio teneva le pubbliche letture della Commedia di Dante. Persino San Lorenzo, patrono dei Medici, quando gli fu chiesto di rinunciare ai tesori ecclesiastici di Roma, si presentò agli invasori barbari con i poveri di Roma. La Professoressa Regina Schwartz nel suo The Curse of Cain ha parlato del retaggio di violenza e di razzismo presente nella Bibbia. Simone Weil osservava dell'Iliade,

Ma nulla di quanto hanno prodotto i popoli d'Europa vale il primo poema conosciuto che sia apparso presso uno di essi. Ritroveranno forse il genio epico quando sapranno credere che nulla è al riparo dalla sorte, quindi non ammirare mai la forza, non odiare i nemici, non disprezzare gli sventurati. E' dubbio che ciò sia prossimo ad accadere.L'Europa non inventò l'alfabeto nè produsse la Bibbia ed il suo Vangelo. Ma come Maria, invece, serbando le parole del Vangelo nel cuore come un Magnificat, ha operato magnificamente. Firenze, nell'arte e nella vita, predica e mette in pratica il Vangelo e la Bibbia, con un rovesciamento delle gerarchie essendo forte per mezzo della cura dei deboli. Basta guardarsi intorno. Le Porte in bronzo dorato del Battistero, il David, in passato del Palazzo del Popolo, la Pietà un tempo del Duomo, il Fra Angelico di San Marco, i Della Robbia ovunque, in Orsanmichele, in Duomo, nei tondi sui timpani dello Spedale degli Innocenti . . .

We thank all who made this conference possible, especially Lapo Mazzei and Carlo Steinhauslin, who obtained funds from the Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, from Findomestic (Italian law requires savings banks to spend much of their profit on culture and charity, a law we would recommend throughout the English-speaking world), and from the Bisenzio Rotary Club; we thank the Mayor and Comune of Florence for the hospitality of the Sala dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, formerly the Palazzo del Popolo, the People's Palace of Florence's Republic, built in the thirteenth century by Arnolfo di Cambio; we thank the Cistercians who now inhabit the beautiful cloisters of Florence's Renaissance Certosa; we thank S.I.S.M.E.L. (Società Internazionale per lo Studio del Medio Evo Latino), and its President, Professor Claudio Leonardi; we thank the great libraries of Florence, the Laurentian Library, the Riccardian and the National Libraries, and their Directors, Doctors Franca Arduini, Giovanna Lazzi, and Antonia Ida Fontana; we thank, too, the makers of fine manuscript facsimiles, Michael and Linda Falter of London and M. Moleiro of Barcelona; we thank the parish priests and rectors and monks of Santa Brigida, the Santuario della Madonna delle Grazie al Sasso and Monte Senario for welcoming us on our pilgrimage questing Irish saints with Bibles in Tuscany; we thank our interpreters and translators, Irene Geronico, Katherine Fay and AD, we thank Livia Michi Montelatici who prepared Tuscan luncheons to serve with Lapo Mazzei's 1435/1999 wine; we thank Francesca Brunori for arranging Villa Agape's hospitality; and we thank Manuela Vestri of 'La Meta' for making the enormous facsimile of the Codex Amiatinus available to us in the Sala dei Cinquecento and our pilgrimages to the Certosa, to Fiesole, to Santa Brigida, to Sasso, to Monte Senario, all possible.

Un grazie a tutti coloro che hanno reso possibile la realizzazione di questo convegno. Un ringraziamento particolare a Lapo Mazzei e a Carlo Steinhauslin, che hanno ottenuto parte dei fondi dall'Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, dalla Findomestic - la legge italiana richiede alle banche di contribuire al finanziamento di eventi culturali e opere caritatevoli, una legge da proporre al mondo di lingua inglese - e dal Rotary Club di Bisenzio. Un ringraziamento va anche al Sindaco ed al Comune di Firenze per l'ospitalità nel Salone dei Cinquecento in Palazzo Vecchio, un tempo il Palazzo del Popolo della Repubblica di Firenze, edificato nel secolo XIII da Arnolfo di Cambio. Dobbiamo uno speciale ringraziamento anche ai cistercensi che occupano gli splendidi chiostri della Certosa rinascimentale di Firenze, alla S.I.S.M.E.L. (Società Internazionale per lo Studio del Medio Evo Latino) ed al suo Presidente, il Professor Claudio Leonardi, alle importanti Biblioteche di Firenze, la Biblioteca Laurenziana, la Riccardiana e la Biblioteca Nazionale, e alle Direttrici, le Dottoresse Franca Arduini, Giovanna Lazzi, e Antonia Ida Fontana. Un grazie di cuore a Michael e Linda Falter di Londra e a M. Moleiro di Barcellona, per i loro raffinati facsimili di manoscritti, e anche ai parroci, ai rettori, ai monaci di Santa Brigida, ai frati del Santuario della Madonna delle Grazie al Sasso e ai padri del Monte Senario per averci accolti nel nostro pellegrinaggio sulle orme dei santi irlandesi in Toscana che portavano con sé le loro Bibbie. Un grazie ancora agli interpreti e ai traduttori, Irene Geronico, Katherine Fay e Assunta D'Aloi. Un grazie a Livia Michi Montelatici per le colazioni secondo la cucina tipica toscana accompagnate dal vino Lapo Mazzei 1435/1999. Grazie ancora a Francesca Brunori, Presidente della CEDER (Cooperativa per l'Editoria, la Documentazione e la Ricerca) per aver provveduto all'ospitalità presso la Villa Agape. Infine un ringraziamento speciale va a Manuela Vestri de "La Meta" per aver messo a nostra disposizione nel Salone dei Cinquecento l'enorme facsimile del Codex Amiatinus come pure per aver reso possibili i pellegrinaggi alla Certosa, a Fiesole, a Santa Brigida, al Sasso, e sul Monte Senario.

INAUGURAZIONE: SALA DEI

CINQUECENTO , Palazzo Vecchio, Firenze/Florence

Mercoledì/Wednesday, 30

maggio/May 2001 9,30-12,00/ 9:30-12:00

Presiede/Chair: Prof.ssa Ida Zatelli, Università di Firenze, University of Florence

OMMAGGIO A FIORETTA MAZZEI/

HOMAGE TO FIORETTA MAZZEI

Salone dei Cinquecento, Palazzo della Signoria,

where Fioretta Mazzei and Giorgio La Pira held the signing of

the Declaration of Peace by

world leaders, and where we held the inaugural lectures of the

City and the Book

Giannozzo

Pucci:

La città

Giovanna

Carocci: Il libro

Della Robbia

LA BIBBIA

AMIATINA : INIZIATIVE DELLA

BIBLIOTECA MEDICEA LAURENZIANA

THE CODEX

AMIATINUS: INITIATIVES OF THE

LAURENTIAN LIBRARY

DOTT.SSA FRANCA ARDUINI,

DIRETTRICE, BIBLIOTECA MEDICEA LAURENZIANA

{ La Bibbia Amiatina è da considerare senza esagerazione il monumento scrittorio più importante del mondo occidentale: il codice contiene infatti la redazione latina più antica, fra quelle conservate, del Vecchio e del Nuovo Testamento in forma completa.

The Codex Amiatinus is considered, without exaggeration, as the most important written monument in the western world; it contains, in fact, the oldest Latin version, of those which are extant, of the complete Old and New Testaments.

Il codice è di eccezionali dimensioni (1029 cc., mm 540x345x253, 53 chili), che comportarono l'utilizzo di 500 capi ovini e fu scritto in onciale da almeno otto copisti fra il 679 e il 716 d.C.; noto è il luogo di composizione, i monasteri di Wearmouth e Jarrow nel Northumberland e noto è anche il committente, l'abate Ceolfrith (morto a Langres nel 716) che, su un modello acquistato in Italia, fece allestire tre codici uguali dei quali uno venne destinato al pontefice Gregorio II e due ai monasteri inglesi gemelli, i cui frammenti sono oggi conservati nella British Library di Londra, con segnature mss. Add. 37777, 45025 e Loan 81. Il prezioso codice fu portato a Roma dopo la morte di Ceolfrido, come è dimostrato da una lettera di ringraziamento del pontefice indirizzata all'abate successore di Ceolfrido. /1

The codex is exceptionally large (1029 cc, 540 x 345 x 253 mm, and weighing 53 kilos, which would have used 500 sheep skins), and was written in uncials by at least eight scribes between 679 and 716 A.D.; what is known is the place of its composition, the monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow in Northumberland, and also its editor, the Abbot Ceolfrith (who died at Langres in 716, Beda Venerabilis: ' Inter quos etiam reverentissimus abba meus Ceolfridus annos natos lxxxiiii, cum esset presbiter annos xlvii, abbas autem annos xxxv, ubi lingonas peruenit, ibi defunctus atque in ecclesiam beatorum geminorum martyrum sepultus est '), who, on a model acquired in Italy, had the three similar codices made, one destined for Pope Gregory II, the other two each for the twin monasteries in England, of which fragments are conserved today in the British Library in London, Manuscripts Add. 37777, 45025 and Loan 81. The precious codex was brought to Rome after Ceolfrith's death, as is witnessed by a letter of thanks written to the abbot succeeding Ceolfrith./1

La sua comparsa nell'Abbazia di San Salvatore sul monte Amiata, fondata secondo la leggenda dal re longobardo Ratchis nell' VIII sec., è testimoniata dalle correzioni apportate su rasura ai versi di dedica, dove «Corpus» è sostituito da «Cenobium»; «Petri» da «Salvatoris» e «Ceolfridus Anglorum» da «Petrus Langobardorum». Da queste inserzioni si deduce che la Bibbia fu acquisita dal monastero di San Salvatore per motivi che non conosciamo e in un ambito cronologico non definito, ma abbastanza circoscritto; non contrasterebbe l'identificazione di Petrus Langobardorum con un Petrus, abate del monastero dopo il 886, anche se i Longobardi erano stati sostituiti nel dominio della Toscana dai Franchi fino dal 774. L'unica cosa certa, allo stato delle nostre conoscenze, è che la Bibbia si trovava a San Salvatore prima del 1035: qui rimase - salvo per un breve viaggio compiuto a Roma fra il 1587 e il 1591, dove fu utilizzata per la prima edizione della Bibbia - fino alla Soppressione Leopoldina del 1782; dopo un soggiorno al monastero cistercense di S. Frediano al Cestello, la Bibbia arrivò nel 1784 nella Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana e fu studiata da Angelo Maria Bandini che ad esso dedicò il primo studio scientifico nel 1785. /2

That it came to the Abbey of San Salvator on Mount Amiata, founded according to legend by the Langobard king, Ratchis, in the eighth century, is witnessed by the corrections made over erasures in the dedicatory verses, where 'Corpus' becomes 'Cenobium', 'Peter', 'Salvatoris', and 'Ceolfridus Anglorum', 'Peter Langobardorum'. From these insertions one can deduce that the Bible was acquired by the monastery of San Salvator, though not knowing why, and in an undetermined, though sufficiently narrow, timespan. This does not contradict the identification of Peter Langobard with a certain Peter, abbot of the monastery after 886, even if the Langobards were replaced in the Tuscan realm by the Franks from 774. All that is clear, according to what we know, is that the Bible was at San Salvator before 1035: and there it remained - except for a brief journey to Rome between 1587 and 1591, where it was used for the first edition of the Bible - before the Leopoldine Suppression of 1782; after a stay at the Cistercian monastery of San Frediano al Cestello, the Bible entered the Laurentian Library in 1784 and was studied by Angelo Maria Bandini, who dedicated to it the first scholarly research, in 1785. /2

Quanto è stato detto è forse sufficiente per capire come l'appartenenza culturale e storica di questo documento, che la Laurenziana conserva religiosamente da più di duecento anni, sia rivendicata almeno idealmente da vari soggetti: la congregazione di Beda il Venerabile a Jarrow ed il monastero di San Salvatore sul Monte Amiata, in particolare, hanno manifestato nel corso del tempo le proprie motivate aspirazioni, se non alla restituzione dell'originale, almeno alla realizzazione di una sua riproduzione e, nel caso dell'Abbazia di San Salvatore, ad un prestito temporaneo di un bene che pure in realtà era destinato al soglio di Pietro.

What has been said is perhaps sufficient for understanding the cultural and historical context of this document, which the Laurentian has conserved religiously for more than two hundred years, while acknowledging at least ideally various claims: the monasteries of the Venerable Bede at Jarrow and of San Salvator on Mount Amiata, in particular, have manifested in the course of time their own desire, if not for the restitution of the original, at least for the carrying out of a reproduction, in the case of the Abbey of San Salvator, of a temporary loan of a masterpiece that in reality was destined for the threshold of Peter.

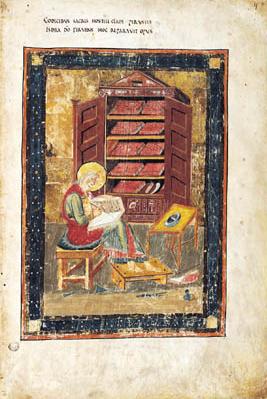

La fama straordinaria del codice è anche legata all'apparato illustrativo del primo fascicolo. Oltre alla carta purpurea contenente il Prologo che ne evidenzia il pregio qualitativo e a quella contenente i versi di dedica, la cui lettura fu chiarita per la prima volta, rispetto all'interpretazione data da Bandini, da Giovanni Battista De Rossi, sulla base dell'analisi paleografica e della lettura delle fonti conservate,/3è presente una miniatura a piena pagina, raffigurante lo scriba e sacerdote ebreo Esdra che copia o riscrive a memoria la Bibbia distrutta. Si tratta certamente di una delle immagini più celebri al mondo, fra quelle presenti su codici e di una di quelle più riprodotte in assoluto. Infatti, Esdra o forse Cassiodoro – secondo altre interpretazioni - vi è rappresentato nell'atto di scrivere, circondato dagli strumenti dello scriptorium tardoantico che sono ai suoi piedi, mentre sullo sfondo è rappresentata una biblioteca, o meglio l'armarium in cui i codici sono riposti orizzontalmente sui piani;

The extraordinary fame of the codex is also

linked to the programme of illuminations in the first

gathering. Besides the purple page for the Prologue which

calls attention to the preciousness of the volume and which

contains the dedicatory verse, of which the reading was made

clear for the first time, compared to the interpretation given

by Bandini, by Giovanni Battista De Rossi, on the basis of

paleographic analysis and from reading extant sources,/3 a miniature is

given taking a full page, showing the Hebrew scribe and

priest, Ezra, who copied and rewrote from memory the destroyed

Bible. It is certainly one of the most famous images in the

world, among those present in books and one of the most

reproduced altogether. In fact, Ezra or perhaps Cassiodorus -

according to other interpretations - is shown in the act of

writing, surrounded by the tools of the scriptorium of

Late Antiquity which are at his feet, while behind him is

shown a library, or better a cupboard in which books are laid

horiziontally on shelves;

DETXXXXXXL

DETXXXXXXL

Ezra preserving the Torah (Cassiodorus? Ceolfrith?

Bede? the Bible). Compare with Lindisfarne

Gospels, St Matthew , 698, just

Northumbrian Codex Amiatinus, Biblioteca

Laurenziana, Florence.xxxx prior to Codex Amiatinus, from copying Codex

Grandior?

For enlarged detail

of Bible cupboard, click here .

Compare with Tomb of Galla Placidia, 440-450,

Mosaic of Ivory Gospels Cupbard,

Ravenna

Philosophy to Boethius, De Philosophiae

Consolationis I.5 Prosa. 523: 'Itaque non tam me loci

huius quam tua facies movet nec bibliothecae potius comptos

ebore ac vitro parietes quam tuae mentis sedem requiro, in qua

non libros sed is quod libris pretium facit, librorum quondam

meorum sententias, collocavi'.

[So I am moved more by the sight

of you than of this place. I seek not so much a library with

its walls ornamented with ivory and glass, as the storeroom of

your mind, in which I have laid up not books, but what makes

them of any value, the opinions set down in my books in times

past.]

un foglio intero piegato contiene la rappresentazione del tabernacolo del tempio nella forma che era consegnata alla tradizione prima che Salomone lo edificasse a Gerusalemme.

while another entire open bifolio contains the representation of the tabernacle in the form that it was given by tradition before Solomon built it in Jerusalem.

L'ottimo stato di conservazione della Bibbia, dovuto alla impossibilità di una consultazione resa ardua dalle stesse dimensioni, alla finalità quasi sacrale che il tempo contribuì a conferirle e successivamente al divieto di usarla, proprio per il pregio e l'antichità, non investe la legatura che fu rifatta più volte. Le testimonianze di almeno due successive legature sono state recentemente individuate nell'archivio storico della Laurenziana, proprio in occasione dell'iniziativa intrapresa recentemente dalla Biblioteca Laurenziana nei confronti della Bibbia Amiatina.

The excellent state of the Bible's preservation, due to the impossibility of consulting it without great difficulty because of its same dimensions, and to its quasi-sacred purpose which time contributed to it, consequently preventing its use due to its value and its age, did not affect the binding, which was redone several times. There are traces of two successive bindings recently noted in the historical archive of the Laurentian, discovered in the recent initiative undertaken by the Biblioteca Laurenziana in relation to the Codex Amiatinus.

E' ora opportuno dare conto di quello che può essere definito un complesso intervento di tutela finalizzato, sia alla acquisizione di nuovi contributi per la conoscenza del venerando codice, sia ad una diffusione, non limitata al mondo degli studiosi, ma rivolta anche ad un pubblico più ampio possibile, senza che ciò influisca negativamente sulla conservazione rigorosa del manoscritto. Non c'è dubbio che in questo programma abbia giocato un ruolo importante l'esempio del Book of Kells, ritenuto un simbolo della civiltà irlandese e come tale generosamente esposto ai visitatori di tutto il mondo. Nulla di tutto ciò era stato mai tentato e neppure immaginato per la Bibbia Amiatina: al contrario l'atteggiamento tradizionale era sempre stato quello abbastanza consueto nei confronti dei nostri tesori librari, di rigorosa conservazione che si traduceva nel divieto tassativo di consultare il codice, se non per motivate ragioni di studio.

It is appropriate now to give an account of what can be defined as a complex operation whose purpose is preservation, both the acquisition of new contributions to the knowledge of the venerated volume, and the sharing of it, not only for the world of scholars, but opening it even to the greatest number of people possible, without this in any way negatively affecting the rigorous conservation of the manuscript. Without doubt, the example of the Book of Kells has played an important role in this programme, held as symbol of Irish civilization and as such generously shown to visitors from all over the world. [As dott.ssa Franca Arduini was saying these words, a volume of the Book of Kells was travelling in exhibition in Australia, its artistry causing excitement amongst Aborigine for its similarity to their dot art.] None of this has ever been attempted or even contemplated for the Codex Amiatinus; on the contrary, the traditional attitude had always been the custom for our library treasures, of rigorous conservation which resulted in strictly forbidding the consulting of the codex, except for scholarly research.

Fino da quando ho assunto la Direzione della Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana nel 1996, mi sono resa conto che quel divieto che impedisce la visione diretta dei manoscritti della Riserva non poteva essere applicato a chi dall'Inghilterra (si trattava di religiosi e di religiose, ma anche di laici, non particolarmente qualificati) chiedeva almeno di contemplare il famoso fascicolo primo che alcune fonti avevano attribuito, in un passato non remoto, allo stesso Codex Grandior; né poteva essere respinta, senza un certo imbarazzo, la richiesta di prestito della Bibbia, inoltrata in occasione della fine del ventesimo secolo dal Comune di Abbadia San Salvatore, che in tempi passati ne aveva anche rivendicato formalmente la restituzione. Il complesso di queste motivazioni ha indotto ad ipotizzare la realizzazione di un facsimile, pur nella consapevolezza delle enormi difficoltà che ne avevano impedito fino ad allora l'esecuzione. Esse consistevano principalmente nella difficoltà di effettuare le riprese fotografiche delle singole carte senza ricorrere ad un radicale intervento che comportava non solo l'asportazione della coperta, ma anche la scucitura dei singoli fascicoli e negli alti costi delle riproduzioni dovuti alla dimensione del manufatto. Il facsimile, inoltre, per sua stessa natura, non avrebbe potuto far altro che riproporre le difficoltà dell'originale, quanto alla consultazione, alla ricerca e persino alla conservazione.

From the time I became Director of the Laurentian Library in 1996, I realized this prohibition blocking the direct observation of reserved manuscripts could not be applied to English visitors (who were clergy, and even laity, and not so qualified) asking at least to contemplate the first famous gathering of pages which several sources have associated, quite recently, with the Codex Grandior [the Pandect of the Bible compiled by Cassiodorus] itself. Nor could we reject, without some embarassment, the request of the loan of the Bible, on the occasion of the end of the twentieth century, made by the city government of the Abbadia San Salvatore, which had also in times past claimed this restitution. All these together led to contemplating making a facsimile, though aware, until then, of the difficulty impeding its being carried out. This consisted principally in the difficulty of taking photographs of each page without recourse to a radical operation, consisting not only of removing the covers, but also unsewing each gathering, and also of the costs of the reproduction owing to the dimensions of this handwork. The facsimile, by its very nature, could not be done without re-experiencing the labour of the original, in relation to its consultation, its research, and even its preservation.

Per una serie di fortunate congiunture sono stati individuati a Firenze due partners che, secondo le rispettive disponibilità finanziarie e professionali, hanno reso possibile l'iniziativa Laurenziana: la Società “La META” di Manuela Vestri ha assunto le spese della riproduzione su fotocolors di tutte le 1029 carte e quelle della stampa di un facsimile unico. Il volume, rilegato artigianalmente nel Laboratorio di restauro della Biblioteca, con una coperta che per modello e materiali ripropone l'ultima fra quelle ottocentesche della Bibbia, è stato donato nel dicembre del 1999, come dovuto risarcimento, all'Abbazia di San Salvatore che oggi lo espone nel suo Museo. E' importante sottolineare che la “restituzione” simbolica, ricollocando nel sito dove la Bibbia ha dimorato a lungo un efficace simulacro dell'originale, potrà contribuire a dare uno spessore culturale ad un contesto storico ed ambientale drasticamente impoverito. Se infatti da una parte le ragioni della conservazione ci inducono ad approvare le scelte, quasi obbligate, della concentrazione dei documenti artistici e librari nei Musei e nelle Biblioteche di conservazione, non c'è dubbio che le spoliazioni effettuate nel corso dei secoli hanno privato il territorio di elementi fondamentali per capirne la tradizione, non solo da parte dei suoi abitanti, ma anche da parte di chi lo visita per ragioni turistiche.

By a series of happy circumstances two partners were found in Florence who, according to their respective financial and scholarly capabilites, were able to fulfil the Laurentian initiative: Manuela Vestri's "La Meta" Association assumed the cost of reproducing in colour all one thousand and twenty nine folios and that of printing one facsimile. The volume, bound by hand in the Laurentian Library's conservation laboratory, with a cover using similar materials and modelled on that given it last in the nineteenth century, was presented in December 1999, as compensation, to the Abbey of San Salvatore who now can show it in their Museum. [In actual fact, the facsimile of the Codex Amiatinus was on display in the Sala dei Cinquecento during this speech, loaned by the Abbey of San Salvator to the City and the Book Congress in Florence.] It is important to emphasize that the symbolic "restitution", replacing a useful likeness of the original in the place where the Bible rested for so long, can give cultural value to a drastically impoverished historical context and region. Though, in fact, on the one hand for conservation reasons we are led to approve the choice, almost mandatory, of concentrating artistic documents and books in museums and libraries, there is no doubt that over the centuries this stripping has robbed regions of fundamental elements for understanding their heritage, not only for the inhabitants, but also for those who visit it.

La SISMEL (Società internazionale per lo studio del medioevo latino), presieduta da Claudio Leonardi, uno dei grandi esperti della tradizione medievale, utilizzando le fotocolors, ha prodotto un CD Rom che costituisce uno strumento di ampia circolazione del testo e di facile uso per ricerche a vari livelli. Le due riproduzioni (cartacea ed informatica) sono state presentate nella Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in occasione della II Settimana per la Cultura “Italia, una cultura da vivere” (27 marzo-2 aprile 2000). Per la prima ed unica volta, sono state anche esposte singolarmente le carte del primo fascicolo a tutti coloro che, non solo per ragioni di studio, hanno potuto liberamente e con l'ausilio di discreti sussidi didattici avvicinarsi all'originale.