FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

JOHN RUSKIN

MORNINGS IN FLORENCE IV

FOURTH MORNING

THE VAULTED BOOK

[Duomo, Santa Maria Novella, Spanish

Chapel]

S early as may be

this morning, let us look for a minute or two into the

cathedral:—I was going to say, entering by one of the side

doors of the aisles;—but we can't do anything else, which

perhaps might not strike you unless you were thinking

specially of it. There are no transept doors; and one never

wanders round to the desolate front. From either of the side

doors, a few paces will bring you to the middle of the nave,

and to the point opposite the middle of the third arch from

the west end; where you will find yourself—if well in the

mid-wave—standing on a circular slab of green porphyry, which

marks the former place of the grave of the bishop Zenobius.

The larger inscription, on the wide circle of the floor

outside of you, records the translation of his body; the

smaller one round the stone at your feet—"quiescimus, domum

hanc quum adimus ultimam"—is a painful truth, I suppose, to

travellers like us, who never rest anywhere now, if we can

help it.

69. Resting here, at any

rate, for a few minutes, look up to the whitewashed vaulting

of the compartment of the roof next the west end.

You will see nothing

whatever in it worth looking at. Nevertheless, look a little

longer.

But the longer you look,

the less you will understand why I tell you to look. It is

nothing but a whitewashed ceiling: vaulted indeed,—but so is

many a tailor's garret window, for that matter. Indeed, now

that you have looked steadily for a minute or so, and are used

to the form of the arch, it seems to become so small that you

can almost fancy it the ceiling of a good-sized lumber-room in

an attic.

Having attained to this

modest conception of it, carry your eyes back to the similar

vault of the second compartment, nearer you. Very little

further contemplation will reduce that also to the similitude

of a moderately-sized attic. And then, resolving to bear, if

possible—for it is worth while,—the cramp in your neck for

another quarter of a minute, look right up to the third vault,

over your head; which, if not, in the said quarter of a

minute, reducible in imagination to a tailor's garret, will at

least sink, like the two others, into the semblance of a

common arched ceiling, of no serious magnitude or majesty.

70. Then, glance quickly

down from it to the floor, and round at the space, (included

between the four pillars), which that vault covers. It is

sixty feet square,1 four hundred square

yards of pavement,—and I believe you will have to look up

again more than once or twice, before you can convince

yourself that the mean-looking roof is swept indeed over all

that twelfth part of an acre. And still less, if I mistake

not, will you, without slow proof, believe, when you turn

yourself round towards the east end, that the narrow niche (it

really looks scarcely more than a niche) which occupies,

beyond the dome, the position of our northern choirs, is

indeed the unnarrowed elongation of the nave, whose breadth

extends round you like a frozen lake. From which experiments

and comparisons, your conclusion, I think, will be, and I am

sure it ought to be, that the most studious ingenuity could

not produce a design for the interior of a building which

should more completely hide its extent, and throw away every

common advantage of its magnitude, than this of the Duomo of

Florence.

Having arrived at this,

I assure you, quite securely tenable conclusion, we will quit

the cathedral by the western door, for once, and as quickly as

we can walk, return to the Green cloister of Sta. Maria

Novella; and place ourselves on the south side of it, so as to

see as much as we can of the entrance, on the opposite side,

to the so-called 'Spanish Chapel.'

There is, indeed, within

the opposite cloister, an arch of entrance, plain enough. But

no chapel, whatever, externally manifesting itself as worth

entering. No walls, or gable, or dome, raised above the rest

of the outbuildings—only two windows with traceries opening

into the cloister; and one story of inconspicuous building

above. You can't conceive there should be any effect of magnitude

produced in the interior, however it has been vaulted or

decorated. It may be pretty, but it cannot possibly look

large.

71. Entering it,

nevertheless, you will be surprised at the effect of height,

and disposed to fancy that the circular window cannot surely

be the same you saw outside, looking so low, I had to go out

again, myself, to make sure that it was.

And gradually, as you

let the eye follow the sweep of the vaulting arches, from the

small central keystone-boss, with the Lamp carved on it, to

the broad capitals of the hexagonal pillars at the

angles,—there will form itself in your mind, I think, some

impression not only of vastness in the building, but of great

daring in the builder; and at last, after closely following

out the lines of a fresco or two, and looking up and up again

to the coloured vaults, it will become to you literally one of

the grandest places you ever entered, roofed without a central

pillar. You will begin to wonder that human daring ever

achieved anything so magnificent.

But just go out again

into the cloister, and recover knowledge of the facts. It is

nothing like so large as the blank arch which at home we

filled with brickbats or leased for a gin-shop under the last

railway we made to carry coals to Newcastle. And if you pace

the floor it covers, you will find it is three feet less one

way, and thirty feet less the other, than that single square

of the Cathedral which was roofed like a tailor's

loft,—accurately, for I did measure here, myself, the floor of

the Spanish chapel is fifty-seven feet by thirty-two.

72. I hope, after this

experience, that you will need no farther conviction of the

first law of noble building, that grandeur depends on

proportion and design—not, except in a quite secondary degree,

on magnitude. Mere size has, indeed, under all disadvantage,

some definite value; and so has mere splendour. Disappointed

as you may be, or at least ought to be, at first, by St.

Peter's, in the end you will feel its size,—and its

brightness. These are all you can feel in it—it is

nothing more than the pump-room at Leamington built

bigger;—but the bigness tells at last: and Corinthian pillars

whose capitals alone are ten feet high, and their acanthus

leaves, three feet six long, give you a serious conviction of

the infallibility of the Pope, and the fallibility of the

wretched Corinthians, who invented the style indeed, but built

with capitals no bigger than hand-baskets.

Vastness has

thus its value. But the glory of architecture is to

be—whatever you wish it to be,—lovely, or grand, or

comfortable,—on such terms as it can easily obtain. Grand, by

proportion—lovely, by imagination—comfortable, by

ingenuity—secure, by honesty: with such materials and in such

space as you have got to give it.

Grand—by proportion, I

said; but ought to have said by disproportion. Beauty

is given by the relation of parts—size, by their comparison.

The first secret in getting the impression of size in this

chapel is the disproportion between pillar and arch.

You take the pillar for granted,—it is thick, strong, and

fairly high above your head. You look to the vault springing

from it—and it soars away, nobody knows where.

73. Another great, but

more subtle secret is in the inequality and

immeasurability of the curved lines; and the hiding of the

form by the colour.

To begin, the room, I

said, is fifty-seven feet wide, and only thirty-two deep. It

is thus nearly one-third larger in the direction across the

line of entrance, which gives to every arch, pointed and

round, throughout the roof, a different spring from its

neighbours.

The vaulting ribs have

the simplest of all profiles—that of a chamfered beam. I call

it simpler than even that of a square beam; for in barking a

log you cheaply get your chamfer, and nobody cares whether the

level is alike on each side: but you must take a larger tree,

and use much more work to get a square. And it is the same

with stone.

And this profile is—fix

the conditions of it, therefore, in your mind,—venerable in

the history of mankind as the origin of all Gothic

tracery-mouldings; venerable in the history of the Christian

Church as that of the roof ribs, both of the lower church of

Assisi, bearing the scroll of the precepts of St. Francis, and

here at Florence, bearing the scroll of the faith of St.

Dominic. If you cut it out in paper, and cut the corners off

farther and farther, at every cut, you will produce a sharper

profile of rib, connected in architectural use with

differently treated styles. But the entirely venerable form is

the massive one in which the angle of the beam is merely, as

it were, secured and completed in stability by removing its

too sharp edge.

74. Well, the vaulting

ribs, as in Giotto's vault, then, have here, under their

painting, this rude profile: but do not suppose the vaults are

simply the shells cast over them. Look how the ornamental

borders fall on the capitals! The plaster receives all sorts

of indescribably accommodating shapes—the painter contracting

and stopping his design upon it as it happens to be

convenient. You can't measure anything; you can't exhaust; you

can't grasp,—except one simple ruling idea, which a child can

grasp, if it is interested and intelligent: namely, that the

room has four sides with four tales told upon them; and the

roof four quarters, with another four tales told on those. And

each history in the sides has its correspondent history in the

roof. Generally, in good Italian decoration, the roof

represents constant, or essential facts; the walls,

consecutive histories arising out of them, or leading up to

them. Thus here, the roof represents in front of you, in its

main quarter, the Resurrection—the cardinal fact of

Christianity; opposite (above, behind you), the Ascension; on

your left hand, the descent of the Holy Spirit; on your right,

Christ's perpetual presence with His Church, symbolized by His

appearance on the Sea of Galilee to the disciples in the

storm.

The correspondent walls

represent: under the first quarter, (the Resurrection), the

story of the Crucifixion; under the second quarter, (the

Ascension), the preaching after that departure, that Christ

will return—symbolized here in the Dominican church by the

consecration of St. Dominic; under the third quarter, (the

descent of the Holy Spirit), the disciplining power of human

virtue and wisdom; under the fourth quarter, (St. Peter's

Ship), the authority and government of the State and Church.

75. The order of these

subjects, chosen by the Dominican monks themselves, was

sufficiently comprehensive to leave boundless room for the

invention of the painter. The execution of it was first

intrusted to Taddeo Gaddi, the best architectural master of

Giotto's school, who painted the four quarters of the roof

entirely, but with no great brilliancy of invention, and was

beginning to go down one of the sides, when, luckily, a man of

stronger brain, his friend, came from Siena. Taddeo thankfully

yielded the room to him; he joined his own work to that of his

less able friend in an exquisitely pretty and complimentary

way; throwing his own greater strength into it, not

competitively, but gradually and helpfully. When, however, he

had once got himself well joined, and softly, to the more

simple work, he put his own force on with a will and produced

the most noble piece of pictorial philosophy2 and divinity existing

in Italy.

This pretty, and,

according to all evidence by me attainable, entirely true,

tradition has been all but lost, among the ruins of fair old

Florence, by the industry of modern mason-critics—who, without

exception, labouring under the primal (and necessarily

unconscious) disadvantage of not knowing good work from bad,

and never, therefore, knowing a man by his hand or his

thoughts, would be in any case sorrowfully at the mercy of

mistakes in a document; but are tenfold more deceived by their

own vanity, and delight in overthrowing a received idea, if

they can.

76. Farther: as every

fresco of this early date has been retouched again and again,

and often painted half over,—and as, if there has been the

least care or respect for the old work in the restorer, he

will now and then follow the old lines and match the old

colours carefully in some places, while he puts in clearly

recognizable work of his own in others,—two critics, of whom

one knows the first man's work well, and the other the last's,

will contradict each other to almost any extent on the

securest grounds. And there is then no safe refuge for an

uninitiated person but in the old tradition, which, if not

literally true, is founded assuredly on some root of fact

which you are likely to get at, if ever, through it only. So

that my general directions to all young people going to

Florence or Rome would be very short: "Know your first volume

of Vasari, and your two first books of Livy; look about you,

and don't talk, nor listen to talking."

77. On those terms, you

may know, entering this chapel, that in Michael Angelo's time,

all Florence attributed these frescos to Taddeo Gaddi and

Simon Memmi.

I have studied neither

of these artists myself with any speciality of care, and

cannot tell you positively, anything about them or their

works. But I know good work from bad, as a cobbler knows

leather, and I can tell you positively the quality of these

frescos, and their relation to contemporary panel pictures;

whether authentically ascribed to Gaddi, Memmi, or any one

else, it is for the Florentine Academy to decide.

The roof, and the north

side, down to the feet of the horizontal line of sitting

figures, were originally third-rate work of the school of

Giotto; the rest of the chapel was originally, and most of it

is still, magnificent work of the school of Siena. The roof

and north side have been heavily repainted in, many places;

the rest is faded and injured, but not destroyed in its most

essential qualities. And now, farther, you must bear with just

a little bit of tormenting history of painters.

There were two Gaddis,

father and son,—Taddeo and Angelo. And there were two Memmis,

brothers,—Simon and Philip.

78. I daresay you will

find, in the modern books, that Simon's real name was Peter,

and Philip's real name was Bartholomew; and Angelo's real name

was Taddeo, and Taddeo's real name was Angelo; and Memmi's

real name was Gaddi, and Gaddi's real name was Memmi. You may

find out all that at your leisure, afterwards, if you like.

What it is important for you to know here, in the Spanish

Chapel, is only this much that follows:—There were certainly

two persons once called Gaddi, both rather stupid in religious

matters and high art; but one of them, I don't know or care

which, a true decorative painter of the most exquisite skill,

a perfect architect, an amiable person, and a great lover of

pretty domestic life. Vasari says this was the father, Taddeo.

He built the Ponte Vecchio; and the old stones of it—which if

you ever look at anything on the Ponte Vecchio but the shops,

you may still see (above those wooden pent-houses) with the

Florentine shield—were so laid by him that they are unshaken

to this day.

He painted an exquisite

series of frescos at Assisi from the Life of Christ; in

which,—just to show you what the man's nature is,—when the

Madonna has given Christ into Simeon's arms, she can't help

holding out her own arms to him, and saying, (visibly,) "Won't

you come back to mamma?" The child laughs his answer—"I love you,

mamma; but I'm quite happy just now."

Well; he, or he and his

son together, painted these four quarters of the roof of the

Spanish Chapel. They were very probably much retouched

afterwards by Antonio Veneziano, or whomsoever Messrs. Crowe

and Cavalcasella please; but that architecture in the descent

of the Holy Ghost is by the man who painted the north transept

of Assisi, and there need be no more talk about the

matter,—for you never catch a restorer doing his old

architecture right again. And farther, the ornamentation of

the vaulting ribs is by the man who painted the

Entombment, No. 31 in the Galerie des Grands Tableaux, in the

catalogue of the Academy for 1874. Whether that picture is

Taddeo Gaddi's or not, as stated in the catalogue, I do not

know; but I know the vaulting ribs of the Spanish Chapel are

painted by the same hand.

79. Again: of the two

brothers Memmi, one or other, I don't know or care which, had

an ugly way of turning the eyes of his figures up and their

mouths down; of which you may see an entirely disgusting

example in the four saints attributed to Filippo Memmi on the

cross wall of the north (called always in Murray's guide the

south, because he didn't notice the way the church was built)

transept of Assisi. You may, however, also see the way the

mouth goes down in the much repainted, but still

characteristic No. 9 in the Uffizi.3

Now I catch the wring

and verjuice of this brother again and again, among the minor

heads of the lower frescoes in this Spanish Chapel. The head

of the Queen beneath Noah, in the Limbo,—(see below) is

unmistakable.

80. Farther: one of the

two brothers, I don't care which, had a way of painting

leaves; of which you may see a notable example in the rod in

the hand of Gabriel in that same picture of the Annunciation

in the Uffizii. No Florentine painter, or any other, ever

painted leaves as well as that, till you get down to Sandro

Botticelli, who did them much better. But the man who painted

that rod in the hand of Gabriel, painted the rod in the right

hand of Logic in the Spanish Chapel,—and nobody else in

Florence, or the world, could.

Farther (and this is the

last of the antiquarian business); you see that the frescoes

on the roof are, on the whole, dark with much blue and red in

them, the white spaces coming out strongly. This is the

characteristic colouring of the partially defunct school of

Giotto, becoming merely decorative, and passing into a

colourist school which connected itself afterwards with the

Venetians. There is an exquisite example of all its

specialities in the little Annunciation in the Uffizii, No.

14, attributed to Angelo Gaddi, in which you see the Madonna

is stupid, and the angel stupid, but the colour of the whole,

as a piece of painted glass, lovely; and the execution

exquisite,—at once a painter's and jeweller's; with subtle

sense of chiaroscuro underneath; (note the delicate shadow of

the Madonna's arm across her breast).

The head of this school

was (according to Vasari) Taddeo Gaddi; and henceforward,

without further discussion, I shall speak of him as the

painter of the roof of the Spanish Chapel,—not without

suspicion, however, that his son Angelo may hereafter turn out

to have been the better decorator, and the painter of the

frescoes from the life of Christ in the north transept of

Assisi,—with such assistance as his son or scholars might

give—and such change or destruction as time, Antonio

Veneziano, or the last operations of the Tuscan railroad

company, may have effected on them.

81. On the other hand,

you see that the frescos on the walls are of paler colours,

the blacks coming out of these clearly, rather than the

whites; but the pale colours, especially, for instance, the

whole of the Duomo of Florence in that on your right, very

tender and lovely. Also, you may feel a tendency to express

much with outline, and draw, more than paint, in the most

interesting parts; while in the duller ones, nasty green and

yellow tones come out, which prevent the effect of the whole

from being very pleasant. These characteristics belong, on the

whole, to the school of Siena; and they indicate here the work

assuredly of a man of vast power and most refined

education, whom I shall call without further discussion,

during the rest of this and the following morning's study,

Simon Memmi.

82. And of the grace and

subtlety with which he joined his work to that of the Gaddis,

you may judge at once by comparing the Christ standing on the

fallen gate of the Limbo, with the Christ in the Resurrection

above. Memmi has retained the dress and imitated the general

effect of the figure in the roof so faithfully that you

suspect no difference of mastership—nay, he has even raised

the foot in the same awkward way: but you will find Memmi's

foot delicately drawn-Taddeo's, hard and rude: and all the

folds of Memmi's drapery cast with unbroken grace and complete

gradations of shade, while Taddeo's are rigid and meagre; also

in the heads, generally Taddeo's type of face is square in

feature, with massive and inelegant clusters or volutes of

hair and beard; but Memmi's delicate and long in feature, with

much divided and flowing hair, often arranged with exquisite

precision, as in the finest Greek coins. Examine successively

in this respect only the heads of Adam, Abel, Methuselah, and

Abraham, in the Limbo, and you will not confuse the two

designers any more. I have not had time to make out more than

the principal figures in the Limbo, of which indeed the entire

dramatic power is centred in the Adam and Eve. The latter

dressed as a nun, in her fixed gaze on Christ, with her hands

clasped, is of extreme beauty: and however feeble the work of

any early painter may be, in its decent and grave

inoffensiveness it guides the imagination unerringly to a

certain point. How far you are yourself capable of filling up

what is left untold and conceiving, as a reality, Eve's first

look on this her child, depends on no painter's skill, but on

your own understanding. Just above Eve is Abel, bearing the

lamb: and behind him, Noah, between his wife and Shem: behind

them, Abraham, between Isaac and Ishmael; (turning from

Ishmael to Isaac), behind these, Moses, between Aaron and

David. I have not identified the others, though I find the

white-bearded figure behind Eve called Methuselah in my notes:

I know not on what authority. Looking up from these groups,

however, to the roof painting, you will at once feel the

imperfect grouping and ruder features of all the figures; and

the greater depth of colour. We will dismiss these

comparatively inferior paintings at once.

83. The roof and walls

must be read together, each segment of the roof forming an

introduction to, or portion of, the subject on the wall below.

But the roof must first be looked at alone, as the work of

Taddeo Gaddi, for the artistic qualities and failures of it.

I. In front, as you

enter, is the compartment with the subject of the

Resurrection. It is the traditional Byzantine composition: the

guards sleeping, and the two angels in white saying to the

women, "He is not here," while Christ is seen rising with the

flag of the Cross.

But it would be

difficult to find another example of the subject, so coldly

treated—so entirely without passion or action. The faces are

expressionless; the gestures powerless. Evidently the painter

is not making the slightest effort to conceive what really

happened, but merely repeating and spoiling what he could

remember of old design, or himself supply of commonplace for

immediate need. The "Noli me tangere," on the right, is

spoiled from Giotto, and others before him; a peacock,

woefully plumeless and colourless, a fountain, an ill drawn

toy-horse, and two toy-children gathering flowers, are

emaciate remains of Greek symbols. He has taken pains with the

vegetation, but in vain. Yet Taddeo Gaddi was a true painter,

a very beautiful designer, and a very amiable person. How

comes he to do that Resurrection so badly?

In the first place, he

was probably tired of a subject which was a great strain to

his feeble imagination; and gave it up as impossible: doing

simply the required figures in the required positions. In the

second, he was probably at the time despondent and feeble

because of his master's death. See Lord Lindsay, II. 273,

where also it is pointed out that in the effect of the light

proceeding from the figure of Christ, Taddeo Gaddi indeed was

the first of the Giottisti who showed true sense of light and

shade. But until Lionardo's time the innovation did not

materially affect Florentine art.

84. II. The Ascension

(opposite the Resurrection, and not worth looking at, except

for the sake of making more sure our conclusions from the

first fresco). The Madonna is fixed in Byzantine stiffness,

without Byzantine dignity.

III. The Descent of the

Holy Ghost, on the left hand. The Madonna and disciples are

gathered in an upper chamber: underneath are the Parthians,

Medes, Elamites, etc., who hear them speak in their own

tongues.

Three dogs are in the

foreground—their mythic purpose the same as that of the two

verses which affirm the fellowship of the dog in the journey

and return of Tobias: namely, to mark the share of the lower

animals in the gentleness given by the outpouring of the

Spirit of Christ.

IV. The Church sailing

on the Sea of the World. St. Peter coming to Christ on the

water.

I was too little

interested in the vague symbolism of this fresco to examine it

with care—the rather that the subject beneath, the literal

contest of the Church with the world, needed more time for

study in itself alone than I had for all Florence.

85. On this, and the

opposite side of the chapel, are represented, by Simon Memmi's

hand, the teaching power of the Spirit of God, and the saving

power of the Christ of God, in the world, according to the

understanding of Florence in his time.

We will take the side of

Intellect first, beneath the pouring forth of the Holy Spirit.

In the point of the arch

beneath, are the three Evangelical Virtues. Without these,

says Florence, you can have no science. Without Love, Faith,

and Hope—no intelligence.

Under these are the four

Cardinal Virtues, the entire group being thus arranged:—

A

B

C

D E F G

A, Charity; flames

issuing from her head and hands.

B, Faith; holds cross and shield, quenching fiery darts.

This symbol, so frequent in modern adaptation from St. Paul's

address to

personal faith, is rare in older art.

C, Hope, with a branch of lilies.

D, Temperance; bridles a black fish, on which she stands.

E, Prudence, with a book.

F, Justice, with crown and baton.

G, Fortitude, with tower and sword.

Under these are the

great prophets and apostles; on the left,[4] David, St. Paul, St.

Mark, St. John; on the right, St. Matthew, St. Luke, Moses,

Isaiah, Solomon. In the midst of the Evangelists, St. Thomas

Aquinas, seated on a Gothic throne.

86. Now observe, this

throne, with all the canopies below it, and the complete

representation of the Duomo of Florence opposite, are of

finished Gothic of Orcagna's school—later than Giotto's

Gothic. But the building in which the apostles are gathered at

the Pentecost is of the early Romanesque mosaic school, with a

wheel window from the duomo of Assisi, and square windows from

the Baptistery of Florence. And this is always the type of

architecture used by Taddeo Gaddi: while the finished Gothic

could not possibly have been drawn by him, but is absolute

evidence of the later hand.

Under the line of

prophets, as powers summoned by their voices, are the mythic

figures of the seven theological or spiritual, and the seven geological

or natural sciences: and under the feet of each of them, the

figure of its Captain-teacher to the world.

I had better perhaps

give you the names of this entire series of figures from left

to right at once. You will see presently why they are numbered

in a reverse order.

Beneath

whom

8. Civil Law. The Emperor Justinian.

9. Canon Law. Pope Clement V.

10. Practical Theology. Peter Lombard.

11. Contemplative Theology. Dionysius the Areopagite.

12. Dogmatic Theology. Boethius.

13. Mystic Theology. St. John Damascene.

14. Polemic Theology. St. Augustine.

For

larger image, click here

7. Arithmetic. Pythagoras.

6. Geometry. Euclid.

5. Astronomy. Zoroaster.

4. Music. Tubalcain.

3. Logic. Aristotle.

2. Rhetoric. Cicero.

1. Grammar. Priscian.

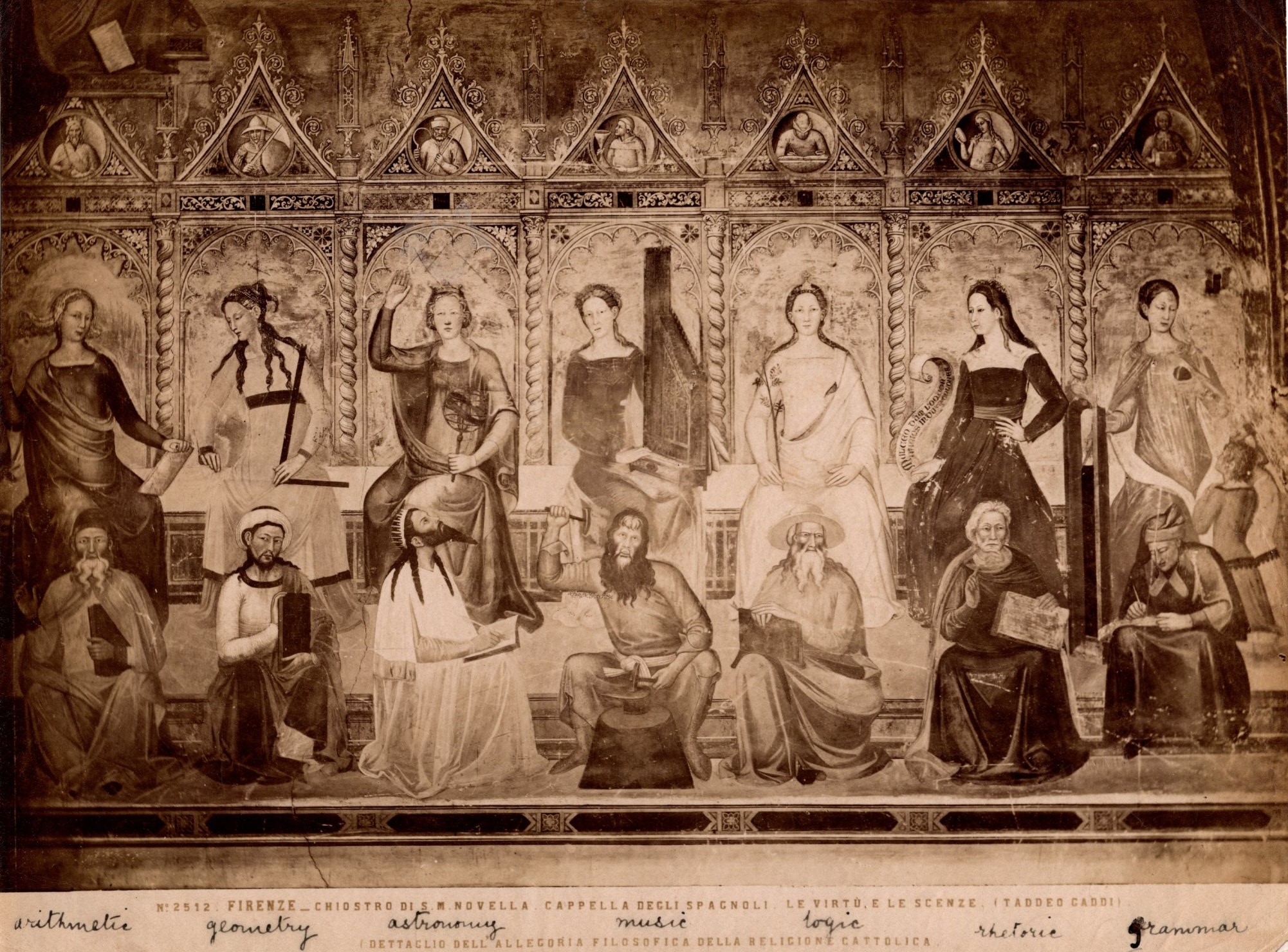

N. 2511. Firenze. Chiostro di S. M. Novella,

Capella degli Spagnoli. Le virtù e le scienze (Taddeo Gaddi).

Dettaglio dell'Allegoria filosofica della religione cattolica

Beneath the figures a Sister has written: 'Civil law,

canon law, practical theology, contemplative theology, dogmatic

theology, mystic theology, polemical theology'

For larger

image, click here

87. Here, then, you have

pictorially represented, the system of manly education,

supposed in old Florence to be that necessarily instituted in

great earthly kingdoms or republics, animated by the Spirit

shed down upon the world at Pentecost. How long do you think

it will take you, or ought to take, to see such a picture? We

were to get to work this morning, as early as might be: you

have probably allowed half an hour for Santa Maria Novella;

half an hour for San Lorenzo; an hour for the museum of

sculpture at the Bargello; an hour for shopping; and then it

will be lunch time, and you mustn't be late, because you are

to leave by the afternoon train, and must positively be in

Rome to-morrow morning. Well, of your half-hour for Santa

Maria Novella,—after Ghirlandajo's choir, Orcagna's transept,

and Cimabue's Madonna, and the painted windows, have been seen

properly, there will remain, suppose, at the utmost, a quarter

of an hour for the Spanish Chapel. That will give you two

minutes and a half for each side, two for the ceiling, and

three for studying Murray's explanations or mine. Two minutes

and a half you have got, then—(and I observed, during my five

weeks' work in the chapel, that English visitors seldom gave

so much)—to read this scheme given you by Simon Memmi of human

spiritual education. In order to understand the purport of it,

in any the smallest degree, you must summon to your memory, in

the course of these two minutes and a half, what you happen to

be acquainted with of the doctrines and characters of

Pythagoras, Zoroaster, Aristotle, Dionysius the Areopagite,

St. Augustine, and the emperor Justinian, and having further

observed the expressions and actions attributed by the painter

to these personages, judge how far he has succeeded in

reaching a true and worthy ideal of them, and how large or how

subordinate a part in his general scheme of human learning he

supposes their peculiar doctrines properly to occupy. For

myself, being, to my much sorrow, now an old person; and, to

my much pride, an old-fashioned one, I have not found my

powers either of reading or memory in the least increased by

any of Mr. Stephenson's or Mr. Wheatstone's inventions; and

though indeed I came here from Lucca in three hours instead of

a day, which it used to take, I do not think myself able, on

that account, to see any picture in Florence in less time than

it took formerly, or even obliged to hurry myself in any

investigations connected with it.

88. Accordingly, I have

myself taken five weeks to see the quarter of this picture of

Simon Memmi's: and can give you a fairly good account of that

quarter, and some partial account of a fragment or two of

those on the other walls: but, alas! only of their pictorial

qualities in either case; for I don't myself know anything

whatever, worth trusting to, about Pythagoras, or Dionysius

the Areopagite; and have not had, and never shall have,

probably, any time to learn much of them; while in the very

feeblest light only,—in what the French would express by their

excellent word 'lueur,'—I am able to understand something of

the characters of Zoroaster, Aristotle, and Justinian. But

this only increases in me the reverence with which I ought to

stand before the work of a painter, who was not only a master

of his own craft, but so profound a scholar and theologian as

to be able to conceive this scheme of picture, and write the

divine law by which Florence was to live. Which Law, written

in the northern page of this Vaulted Book, we will begin quiet

interpretation of, if you care to return hither, to-morrow

morning.

Notes

1· · Approximately.

Thinking I could find the dimensions of the Duomo anywhere, I

only paced it myself,—and cannot, at this moment, lay my hand

on English measurements of it.

2· · There

is no philosophy taught either by the school of Athens

or Michael Angelo's 'Last Judgment,' and the 'Disputa' is

merely a graceful assemblage of authorities, the effects of

such authority not being shown.

3· · This

picture

bears the inscription (I quote from the French catalogue, not

having verified it myself), "Simon Martini, et Lippus Memmi de

Senis me pinxerunt." I have no doubt whatever, myself, that

the two brothers worked together on these frescoes of the

Spanish Chapel: but that most of the Limbo is Philip's, and

the Paradise, scarcely with his interference, Simon's.

4·

I can't find my note of the first one on the left;

answering to Solomon, opposite.

GO TO FIFTH

MORNING

FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII,

VIII,

IX,

X

|| MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA