A special interest attaches to this poem as the one which induced Robert Browning to seek Miss Barrett's acquaintance. She herself had been rather inclined to think lightly of it because it was, in some sense, written to order, and that with extraordinary rapidity. In a letter to H. S. Boyd, dated August 1, 1844, she gives the following account of its origin: ' Last Saturday, on its being discovered that my first volume consisted of only 208 pages, and my second of 280 pages, Mr. Moxon uttered a cry of reprehension . . . and wanted to tear away several poems from the end of the second volume, and tie them on to the end of the first! I could not and would not hear of this because I had set my heart on having ' Dead Pan' to conclude with. So there was nothing for it but to finish a ballad poem called ' Lady Geraldine's Courtship,' which was lying by me, and I did so by writing — i.e., composing, — one hundred and forty lines last Saturday. I seemed to be in a dream all day. Long lines, too, — fifteen syllables each!' Elsewhere she entreats Mr. Boyd never to tell anybody in what haste the poem was written. This highly colored rhymed romance of modern life proved far more attractive to the general reader than some of the more elaborate and more truly artistic pieces in the edition of 1844. It was also a special favorite both with Carlyle and Miss Martineau.

♫ LADY GERALDINE'S COURTSHIP: A ROMANCE OF THE AGE

A Poet writes to his Friend . Place — A Room in Wycombe Hall . TIME — Late in the evening .

I

Down the purple of this chamber tears should scarcely run at will.

I am humbled who was humble. Friend,

I bow my head before you:

You should lead me to my peasants, but their faces are too still.

II

There's a lady, an earl's daughter, — she is proud and she is noble,

And she treads the crimson carpet and she breathes the perfumed air,

And a kingly blood sends glances up, her princely eye to trouble,

And the shadow of a monarch's crown is softened in her hair.

III

She has halls and she has castles, and the resonant steam eagles

Follow far on the directing of her floating dove-like hand —

With a thunderous vapour trailing, underneath the starry vigils,

So to mark the the blasted heaven, the measure of her land.

IV

There be none of England's daughters, who can show a prouder presence;

Upon princely suitors' suing, she has looked in her disdain.

She was sprung of English nobles, I was born of English peasants;

What was I that I should love her — save for competence to pain?

V

I was only a poor poet, made for singing at her casement,

As the finches or the thrushes, while she thought of other things.

Oh, she walked so high above me, she appeared to my abasement,

In her lovely silken murmur, like an angel clad in wings!

VI

Many vassals bow before her as her carriage sweeps their doorways;

She has blessed their little children — as a priest or queen were she:

Oh, too tender, or too cruel far, her smile upon the poor was,

For I thought it was the same smile which she used to smile on me .

VII

She has voters in the Commons, she has lovers in the palace —

And, of all the fair court-ladies, few have jewels half as fine;

Even the Prince has named her beauty 'twixt the red wine and the chalice:

Oh, and what was I to love her? my beloved, my Geraldine!

VIII

Yet I could not choose but love her — I was born to poet-uses —

To love all things set above me, all of good and all of fair.

Nymphs of old Parnassus, we are wont to call the Muses;

And in silver-footed climbing, poets pass from mount to star.

IX

And because I was a poet, and because the public praised me,

With their critical deduction for the modern writer's fault,

I could sit at rich men's tables, — though the courtesies that raised me,

Still suggested clear between us the pale spectrum of the salt.

X

And they praised me in her presence —

' Will your book appear this summer?'

Then returning to each other — ' Yes, our plans are for the moors.'

Then with whisper dropped behind me —

' There he is! the latest comer.

Oh, she only likes his verses! what is over, she endures.

XI

' Quite low-born, self-educated! somewhat gifted though by nature,

And we make a point of asking him, — of being very kind.

You may speak, he does not hear you! and, besides, he writes no satire, —

The new charmers who keep serpents with the antique sting resigned.

XII

I grew colder, I grew colder, as I stood up there among them,

Till as frost intense will burn you, the cold scorning scorched my brow;

When a sudden silver speaking, gravely cadenced, over-rung them,

And a sudden silken stirring touched my inner nature through.

XIII

I looked upward and beheld her: with a calm and regnant spirit,

Slowly round she swept her eyelids, and said clear before them all —

' Have you such superfluous honor, sir, that, able to confer it

You will come down, Mr. Bertram, as my guest to Wycombe Hall?'

XIV

Here she paused — she had been paler at the first word of her speaking,

But, because a silence followed it, blushed somewhat, as for shame:

Then, as scorning her own feeling, resumed calmly — ' I am seeking

More distinction than these gentlemen think worthy of my claim.

XV

' Ne'ertheless, you see, I seek it — not because I am a woman,'

(Here her smile sprang like a fountain and, so, overflowed her mouth)

' But because my woods in Sussex have some purple shades at gloaming

Which are worthy of a king in state, or poet in his youth.

XVI

' I invite you, Mister Bertram, to no hive for worldly speeches —

Sir, I scarce should dare — but only where God asked the thrushes first:

And if you will sing beside them, in the covert of my beeches,

I will thank you for the woodlands, . . . for the human world, at worst.'

XVII

Then, she smiled around right childly, then, she gazed around right queenly,

And I bowed — I could not answer! Alternated light and gloom —

While as one who quells the lions, with a steady eye serenely,

She, with level fronting eyelids, passed out stately from the room.

XVIII

Oh, the blessed woods of Sussex, I can hear them still around me,

With their leafy tide of greenery still rippling up the wind!

Oh, the cursed woods of Sussex! Oh, the cruel love than bound me

Up against the boles of cedars. to be shamed where I pined!

Oh, the cursed woods of Sussex! where the hunter's arrow found me,

When a fair face and a tender voice had made me mad and blind!

XIX

In that ancient hall of Wycombe, thronged the numerous guests invited,

And the lovely London ladies trod the floors with gliding feet;

And their voices low with fashion, not with feeling, softly freighted

All the air about the windows, with elastic laughters sweet.

XX

For at eve the open windows flung their light out on the terrace

Which the floating orbs of curtains did with gradual shadow sweep,

While the swans upon the river, fed at morning by the heiress,

Trembled downward through their snowy wings, at music in their sleep.

XXI

And there evermore was music, both of instrument and singing,

Till the finches of the shrubberies, grew restless in the dark;

But the cedars stood up motionless, each in a moonlight ringing,

And the deer, half in the glimmer, strewed the hollows of the park.

XXII

And though sometimes she would bind me with her silver-corded speeches

To commix my words and laughter with the converse and the jest,

Oft I sat apart, and, gazing on the river, through the beeches,

Heard, as pure the swans swam down it, her pure voice o'erfloat the rest.

XXIII

In the morning, horn of huntsman, hoof of steed and laugh of rider,

Spread out cheery from the court-yard till we lost them in the hills,

While herself and other ladies, and her suitors left beside her,

Went a-wandering up the gardens through the laurels and abeles.

XXIV

Thus, her foot upon the new-mown grass, bareheaded — with the flowings

Of the virginal white vesture, gathered closely to her throat,

And the golden ringlets in her neck just quickened by her going,

And appearing to breathe sun for air, and doubting if to float, —

XXV

With a bunch of dewy maple, which her right hand held above her,

And which trembled a green shadow in betwixt her and the skies,

As she turned her face in going, thus, she drew me on to love her,

And to worship the deep meaning of the smile hid in her eyes.

XXVI

For her eyes alone smile constantly: her lips have serious sweetness,

And her front was calm — the dimple rarely ripples on the cheek;

But her deep blue eyes smile constantly, — as if they had by fitness

Won the secret of a happy dream, she did not care to speak.

XXVII

Thus she drew me the first morning, out across into the garden,

And I walked among her noble friends. and could not keep behind.

Spake she unto all and unto me — ' Behold, I am the warden

Of the birds within these lindens, which are cages in their mind.

XXVIII

'But here, in this swarded circle, into which the lime-walk brings us,

Whence the beeches rounded greenly, stand away in reverent fear,

I will let no music enter, saving what the fountain sings us

Which the lilies round the basin, may seem pure enough to hear.

XXIX

'And the air that waves the lilies, waves this slender jet of water

Like a holy thought sent feebly up from soul of fasting saint!

Whereby lies a marble Silence, sleeping (Lough the sculptor wrought her),

So asleep, she is forgetting to say Hush! — a fancy quaint.

XXX

'Mark how heavy white her eyelids! not a dream between them lingers;

And the left hand's index droppeth from the lips upon the cheek:

And the right hand, — with the symbol-rose held slack within the fingers, —

Has fallen backward in the basin — yet this Silence will not speak!

XXXI

'That the essential meaning growing, may exceed the special symbol,

Is the thought, as I conceive it: it applies more high and low, —

Your true noblemen will often, through right nobleness, grow humble,

And assert an inward honor by denying outward show.'

XXXII

'Yes, your Silence,' said I, ' truly, holds her symbol-rose but slackly,

Yet she holds it — or would scarcely be a Silence to our ken:

And your nobles wear their ermine on the outside, or walk blackly

In the presence of the social law, as most ignoble men.

XXXIII

' Let the poets dream such dreaming! Madam, in these British islands

'Tis the substance that wanes ever, 'tis the symbol that exceeds:

Soon we shall have nought but symbol! and, for statues like this Silence,

Shall accept the rose's marble — in another case, the weed's.'

XXXIV

'I let your dream,' she retorted, — 'and I grant where'er you go, you

Find for things, names — shows for actions, and pure gold for honor clear:

But when all is run to symbol in the Social, I will throw you

The world's book, which now reads drily, and sit down with Silence here.'

XXXV

Half in playfulness she spoke, I thought, and half in indignation;

Her friends turned her words to laughter, while her lovers deemed her fair:

A fair woman, flushed with feeling, in her noble-lighted station

Near the statue's white reposing — and both bathed in sunny air!

XXXVI

With the trees round, not so distant, but you heard their vernal murmur,

And beheld in light and shadow the leaves in and outward move,

And the little fountain leaping toward the sun-heart to be warmer,

Then recoiling backward, trembling with too much light above.

XXXVII

'Tis a picture for remembrance. And thus, morning after morning,

Did I follow as she drew me, by the spirit, to her feet —

Why, her greyhound followed also! dogs — we both were dogs for scorning —

To be sent back when she pleased it, and her path lay through the wheat.

XXXVIII

And thus, morning after morning, spite of oath, and spite of sorrow,

Did I follow at her drawing, while the week-days passed along, —

Just to feed the swans this noontide, or to see the fawns to-morrow,

Or to teach the hill-side echo, some sweet Tuscan in a song.

XXXIX

Ay, and sometimes on the hill-side, while we sate down in the gowans,

With the forest green behind us, and its shadow cast before,

And the river running under, and across it, from the rowans

A brown partridge whirring near us, till we felt the air it bore, —

XL

There, obedient to her praying, did I read aloud the poems

Made by Tuscan flutes, or instruments more various, of our own;

Read the pastoral parts of Spenser — or the subtle interflowings

Found in Petrarch's sonnets — here's the book — the leaf is folded down!

XLI

Or at times a modern volume, — Wordsworth's solemn-thoughted idyl,

Howitt's ballad-dew, or Tennyson's enchanted reverie, —

Or from Browning some ' Pomegranate,' which, if cut deep down the middle,

Shows a heart within blood-tinctured, of a veined humanity.

XLII

Or I read there sometimes, hoarsely, some new poem of my making:

Oh, your poets never read their own best verses to their worth,

For the echo, in you, breaks upon the words which you are speaking,

And the chariot-wheels jar in the gate, through which you drive them forth.

XLIII

After, when we were grown tired of books, the silence round us flinging

A slow arm of sweet compression, felt with beatings at the breast,

She would break out, on a sudden, in a gush of woodland singing,

Like a child's emotion in a god — a naiad tired of rest.

XLIV

Oh, to see or hear her singing! scarce I know which is divinest,

For her looks sing too — she modulates her gestures on the tune,

And her mouth stirs with the song, like song; and when the notes are finest,

'Tis the eyes that shoot out vocal light and seem to swell them on.

XLV

Then we talked — oh, how we talked! her voice, so cadenced in the talking,

Made another singing — of the soul! a music without bars —

While the leafy sounds of woodlands, humming round where we were walking,

Brought interposition worthy-sweet, — as skies about the stars.

XLVI

And she spake such good thoughts natural, as if she always thought them;

And had sympathies so ready, open, free as bird on branch,

Just as ready to fly east as west, whichever way besought them,

In the birchen-wood a chirrup, or a cockcrow in the grange.

XLVII

In her utmost lightness there is truth — and often she speaks lightly,

Has a grace in being gay, which mourners even approve,

For the root of some grave earnest thought is understruck so rightly

As to justify the foliage and the waving flowers above.

XLVIII

And she talked on — we talked truly! upon all things — substance — shadow,

Of the sheep that browsed the grasses — of the reapers in the corn,

Of the little children from the schools, seen winding through the meadow —

Of the poor rich world beyond them, still kept poorer by its scorn!

XLIX

So of men, and so, of letters — books are men of higher stature,

And the only men that speak aloud for future times to hear!

So, of mankind in the abstract, which grows slowly into nature,

Yet will lift the cry of ' progress,' as it trod from sphere to sphere

L

And her custom was to praise me, when I said, — ' The Age culls simples,

With a broad clown's back turned broadly, to the glory of the stars —

We are gods by our own reck'ning, — and may well shut up the temples,

And wield on, amid the incense-steam, the thunder of our cars.

LI

' For we throw out acclamations of self-thanking, self-admiring,

With, at every mile run faster, — ' O the wondrous, wondrous age! '

Little thinking if we work our SOULS as nobly as our iron,

Or if angels will commend us at the goal of pilgrimage.

LII

' Why, what is this patient entrance into nature's deep resources

But the child's most gradual learning to walk upright without bane —?

When we drive out, from the cloud of steam, majestical white horses,

Are we greater than the first men who led black ones by the mane?

LIII

' If we sided with the eagles, if we struck the stars in rising,

If we wrapped the globe intensely with one hot electric breath,

'Twere but power within our tether — no new spirit-power conferring —

And in life we were not greater men, nor bolder men in death.'

LIV

She was patient with my talking; and I loved her — loved her certes

As I loved all Heavenly objects, with uplifted eyes and hands;

As I loved pure inspirations, loved the graces, loved the virtues,

In a Love content with writing his own name, on desert sands.

LV

Or at least I thought so, purely! — thought, no idiot Hope was raising

Any crown to crown Love's silence — silent Love that sate alone —

Out, alas! the stag is like me — he that tries to go on grazing

With the great deep gun-wound in his neck, then reels with sudden moan.

LVI

It was thus I reeled! I told you that her hand had many suitors;

But she rose above them, smiling down, as Venus down the waves —

And with such a gracious coldness, that they cannot press their futures

On the present of her courtesy, which yieldingly enslaves.

LVII

And this morning, as I sat alone, within the inner chamber

With the great saloon beyond it, lost in pleasant thought serene,

For I had been reading Camoëns — that poem you remember,

Which his lady's eyes are praised in, as the sweetest ever seen.

LVIII

And the book lay open, and my thought flew from it, taking from it

A vibration and impulsion to an end beyond its own,

As the branch of a green osier, when a child would overcome it,

Springs up freely from his clasping, and goes swinging in the sun.

LIX

As I mused I heard a murmur — it grew deep as it grew longer —

Speakers using earnest language — ' Lady Geraldine, you would! '

And I heard a voice that pleaded, ever on in accents stronger,

As a sense of reason gave it power to make its rhetoric good.

LX

Well I knew that voice — it was an earl's, of soul that matched his station,

Of a Soul complete in lordship — might and right read on his brow;

Very finely courteous — far too proud to doubt his domination

Of the common people, — he atones for grandeur by a bow.

LXI

High straight forehead, nose of eagle, cold blue eyes, of less expression

Than resistance, — coldly casting off the looks of other men,

As steel, arrows; — unelastic lips which seem to taste possession

And be cautious lest the common air should injure or distrain.

LXII

For the rest, accomplished, upright, — ay, and standing by his order

With a bearing not ungraceful; fond of arts, and letters too;

Just a good man made a proud man, — as the sandy rocks that border

A wild coast, by circumstances, in a regnant ebb and flow.

LXIII

Thus, I knew that voice — I heard it — and I could not help the hearkening:

In the room I stood up blindly, and my burning heart within

Seemed to seethe and fuse my senses, till they ran on all sides darkening,

And scorched, weighed, like melted metal, round my feet that stood therein.

LXIV

And that voice, I heard it pleading, for love's sake — for wealth, position,

For the sake of liberal uses and great actions to be done —

And she answered, answered gently, — 'Nay, my lord, the old tradition

Of your Normans, by some worthier hand than mine is, should be won.'

LXV

' Ah, that white hand!' he said quickly, — and in his he either drew it,

Or attempted — for with gravity and instance she replied,

'Nay, indeed, my lord, this talk is vain, and we had best eschew it

And pass on, like friends, to other points less easy to decide.'

LXVI

What he said again, I know not. It is likely that his trouble

Worked his pride up to the surface, for she answered in slow scorn —

'And your lordship judges rightly. Whom I marry, shall be noble,

Ay, and wealthy. I shall never blush to think how he was born.'

LXVII

There, I maddened! her words stung me. Life swept through me into fever,

And my soul sprang up astonished, sprang, full-statured in an hour.

Know you what it is when anguish, with apocalyptic NEVER ,

To a Pythian height dilates you — and despair sublimes to power?

LXVIII

From my brain, the soul-wings budded! — waved a flame about my body,

Whence conventions coiled to ashes. I felt self-drawn out, as man,

From amalgamate false natures, and I saw the skies grow ruddy

With the deepening feet of angels, and I knew what spirits can.

LXIX

I was mad — inspired — say either! anguish worketh inspiration!

Was a man, or beast — perhaps so, for the tiger roars, when speared;

And I walked on, step by step, along the level of my passion —

Oh my soul! and passed the doorway to her face, and never feared.

LXX

He had left her, — peradventure, when my footstep proved my coming —

But for her — she half arose, then sate — grew scarlet and grew pale:

Oh, she trembled! — 't is so always with a worldly man or woman

In the presence of true spirits; — what else can they do but quail?

LXXI

Oh, she fluttered like a tame bird, in among its forest brothers,

Far too strong for it! then drooping, bowed her face upon her hands;

And I spake out wildly, fiercely, brutal truths of her and others:

I , she planted in the desert, swathed her, windlike, with my sands.

LXXII

I plucked up her social fictions, bloody-rooted, though leaf-verdant, —

Trod them down with words of shaming, — all the purple and the gold.

All the ' landed stakes' and Lordships — all that spirits pure and ardent

Are cast out of love and reverence, because chancing not to hold.

LXXIII

' For myself I do not argue,' said I, ' though I love you, Madam,

But for better souls that nearer to the height of yours have trod:

And this age shows, to my thinking, still more infidels to Adam

Than directly, by profession, simple infidels to God.

LXXIV

' Yet, O God' (I said), ' O grave,' I said, 'O mother's heart and bosom,

With whom first and last are equal, saint and corpse and little child!

We are fools to your deductions, in these figments of heart-closing;

We are traitors to your causes, in these sympathies defiled!

LXXV

'Learn more reverence, Madam, not for rank or wealth — that needs no learning:

That comes quickly — quick as sin does! ay, and often works to sin;

But for Adam's seed, MAN! Trust me, 'tis a clay above your scorning,

With God's image stamped upon it, and God's kindling breath within.

LXXVI

'What right have you, Madam, gazing in your shining mirror daily,

Getting so, by heart, your beauty, which all others must adore, —

While you draw the golden ringlets down your fingers, to vow gaily,

You will wed no man that's only good to God, — and nothing more?

LXXXVII

'Why, what right have you, made fair by that same God, — the sweetest woman

Of all women He has fashioned — with your lovely spirit-face

Which would seem too near to vanish, if its smile were not so human,

And your voice of holy sweetness, turning common words to grace:

LXXVIII

'What right can you have, God's other works, to scorn, despise, . . . revile them

In the gross, as mere men, broadly — not as noble men, forsooth, —

But as Parias of the outer world, forbidden to assoil them

In the hope of living, — dying, — near that sweetness of your mouth?

LXXIX

'Have you any answer, Madam? If my spirit were less earthly,

If its instrument were gifted with more vibrant silver strings,

I would kneel down where I stand, and say — 'Behold me! I am worthy

Of thy loving, for I love thee. I am worthy as a king.

LXXX

' As it is — your ermined pride, I swear, shall feel this stain upon her,

That I, poor, weak, tost with passion, scorned by me and you again,

Love you, Madam — dare to love you — to my grief and your dishonor —

To my endless desolation, and your impotent disdain!'

LXXXI

More mad words like these — mere madness! friend, I need not write them fuller,

For I hear my hot soul dropping on the lines in showers of tears —

Oh, a woman! friend, a woman! Why, a beast had scarce been duller

Than roar bestial loud complaints against the shining of the spheres.

LXXXII

But at last there came a pause. I stood all vibrating with thunder

Which my soul had used. The silence drew her face up like a call.

Could you guess what word she uttered? She looked up, as if in wonder,

With tears beaded on her lashes, and said 'Bertram!' It was all.

LXXXIII

If she had cursed me — and she might have — or if even, with queenly bearing

Which at need is used by women, she had risen up and said,

'Sir, you are my guest, and therefore I have given you a full hearing —

Now, beseech you, choose a name exacting somewhat less, instead — '

LXXXIV

I had borne it! — but that 'Bertram' — why, it lies there on the paper

A mere word, without her accents, — and you cannot judge the weight

Of the calm which crushed my passion! I seemed swimming in a vapor;

And her gentleness did shame me, whom her scorn made desolate.

LXXXV

So, struck backward and exhausted by that inward flow of passion

Which had passed, in deadly rushing, into forms of abstract truth,

With a logic agonizing through unfit denunciation, —

And with youth's own anguish turning grimly gray the hairs of youth, —

LXXXVI

With the sense accursed and instant, that if even I spake wisely

I spake basely — using truth, — if what I spake indeed was true—

To avenge wrong on a woman — her , who sate there weighing nicely

A poor manhood's worth, found guilty of such deeds as I could do! —

LXXXVII

With such wrong and woe exhausted — what I suffered and occasioned, —

As a wild horse, through a city, runs with lightning in his eyes,

And then dashing at a church's cold and passive wall, impassioned,

Strikes the death into his burning brain, and blindly drops and dies —

LXXXVIII

So I fell, struck down before her! Do you blame me, friend, for weakness?

'T was my strength of passion slew me! — fell before her like a stone;

Fast the dreadful world rolled from me, on its roaring wheels of blackness!

When the light came I was lying in this chamber — and alone.

LXXXIX

Oh, of course, she charged her lacqueys to bear out the sickly burden,

And to cast it from her scornful sight, — but not beyond the gate;

She is too kind to be cruel, and too haughty not to pardon

Such a man as I — 'twere something to be level to her hate.

XC

But for me — you now are conscious why, my friend, I write this letter,

How my life is read all backward, and the charm of life undone.

I shall leave this house at dawn — I would to-night, if I were better —

And I charge my soul to hold my body strengthened for the sun.

XCI

When the sun has dyed the oriel, I depart, with no last gazes,

No weak moanings — one word only, left in writing for her hands, —

Out of reach of her derisions, and some unavailing praises,

To make front against this anguish in the far and foreign lands.

XCII

Blame me not. I would not squander life in grief — I am abstemious.

I but nurse my spirit's falcon that its wing may soar again.

There's no room for tears of weakness in the blind eyes of a Phemius:

Into work the poet kneads them — and he does not die till then .

CONCLUSION

I

Bertram finished the last pages, while along the silence ever

Still in hot and heavy splashes, fell his tears on every leaf.

Having ended, he leans backward in his chair, with lips that quiver

From the deep unspoken, ay, and deep unwritten thoughts of grief.

II

Soh! how still the lady standeth! 'tis a dream — a dream of mercies!

'Twixt the purple lattice-curtains, how she standeth still and pale!

'Tis a vision, sure, of mercies, sent to soften his self-curses,

Sent to sweep a patient quiet, o'er the tossing of his wail.

III

'Eyes,' he said, 'now throbbing through me! are ye eyes that did undo me?

Shining eyes, like antique jewels set in Parian statue-stone!

Underneath that calm white forehead, are ye ever burning torrid

O'er the desolate sand-desert of my heart and life undone?'

IV

With a murmurous stir uncertain, in the air, the purple curtain

Swelleth in and swelleth out around her motionless pale brows,

While the gliding of the river sends a rippling noise for ever

Through the open casement whitened by the moonlight's slant repose.

V

Said he — ' Vision of a lady! stand there silent, stand there steady!

Now I see it plainly, plainly; now I cannot hope or doubt —

There, the cheeks of calm expression — there, the lips of silent passion,

Curvéd like an archer's bow, to send the bitter arrows out.'

VI

Ever, evermore the while in a slow silence she kept smiling, —

And approached him slowly, slowly, in a gliding measured pace;

With her two white hands extended, as if praying one offended,

And a look of supplication gazing earnest in his face.

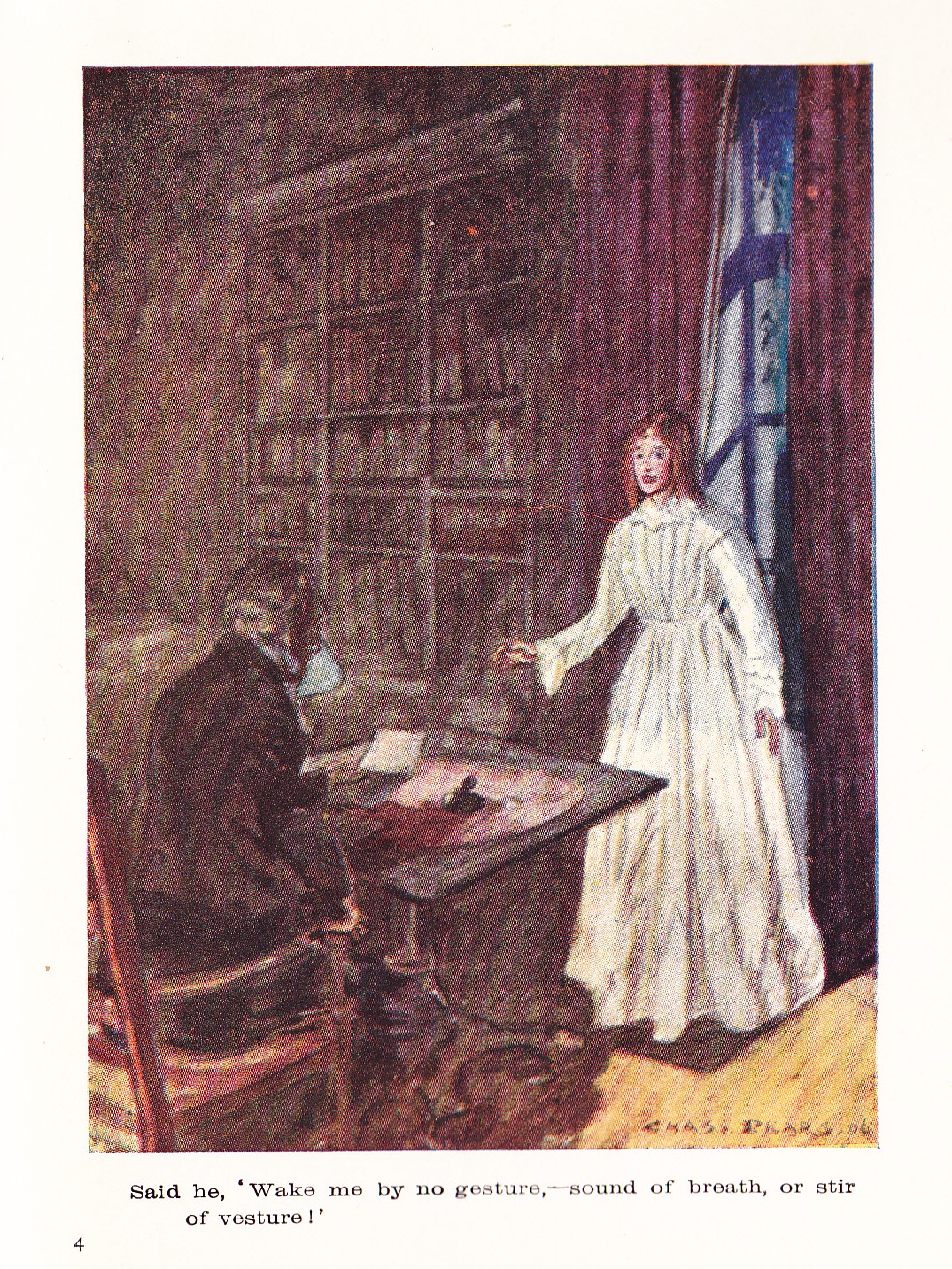

VII

Said he — ' Wake me by no gesture, — sound of breath, or stir of vesture!

Let the blesséd apparition melt not yet to its divine!

No approaching — hush! no breathing! or my heart must swoon to death in

The too utter life thou bringest, — O thou dream of Geraldine!'

VIII

Ever, evermore the while in a slow silence she kept smiling —

But the tears ran over lightly from her eyes and tenderly;

'Dost thou, Bertram, truly love me? Is no woman far above me

Found more worthy of thy poet-heart, than such a one as I ?'

IX

Said he — ' I would dream so ever, like the flowing of that river,

Flowing ever in a shadow, greenly onward to the sea!

So, thou vision of all sweetness — princely to a full completeness —

Would my heart and life flow onward — deathward — through this dream of THEE!'

X

Ever, evermore the while in a slow silence she kept smiling, —

While the shining tears ran faster down the blushing of her cheeks;

Then with both her hands enfolding both of his, she softly told him,

'Bertram, if I say I love thee, . . . 'tis the vision only speaks.'

XI

Softened, quickened to adore her, on his knee he fell before her —

And she whispered low in triumph, — 'It shall be as I have sworn.

Very rich he is in virtues, — very noble — noble, certes;

And I shall not blush in knowing that men call him lowly born.'

Additional Reading:

Anna Jameson, Loves of the Poets, particularly Chapter XII, The Fair Geraldine

Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, Letters, edited by their son, Robert Browning

Wellesley College, Browning Collection

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh

IN STOCK

IN STOCKElizabeth Barrett Browning. Aurora Leigh and Other Poems. Edited, John Robert Glorney Bolton and Julia Bolton Holloway. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1995. xx + 517 pp. ISBN 0-14-043412-7

IN STOCK

Oh Bella Libertà! Le Poesie di Elizabeth Barrett Browning. A cura di Rita Severi e Julia Bolton Holloway. Firenze: Le Lettere, 2022. 290 pp.

LIMITED EDITION

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

SONNETS AND BALLAD

IN ENGLISH AND ITALIAN

Two hundred and fifty

numbered, signed editions of Elizabeth Barrett

Browning's Sonnets from the Portuguese, Sonnet

'On Hiram Powers' Greek Slave', and the ballad, Runaway

Slave at Pilgrim's Point, are edited,

translated, typeset in William Morris Troy and Golden

fonts, handbound in hand-marbled papers. Elizabeth

finally, shyly, gave the sonnet cycle to Robert in

Bagni di Lucca, Italy, after the birth of their child,

'Pen', though she had written them during their

Wimpole Street, London, courtship. Robert immediately

had them published. These volumes are produced in the

English Cemetery in Florence, Italy, where both

Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Hiram Powers are

buried. Their sales help fund the restoration of the

Swiss-owned, so-called 'English' Cemetery.

FLORIN WEBSITE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

New: Dante vivo || White Silence

To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's PayPal button:

THANKYOU!