FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

JOHN RUSKIN

MORNINGS IN FLORENCE I

FIRST MORNING

SANTA CROCE

[Giotto, Campanile, Santa

Croce, de' Bardi Chapel, Baptistry, Santa Maria

Novella, Arnolfo di Cambio, Duomo, Certosa]

F there be one artist, more than another, whose

work it is desirable that you should examine in Florence,

supposing that you care for old art at all, it is Giotto. You

can, indeed, also see work of his at Assisi; but it is not

likely you will stop there, to any purpose. At Padua there is

much; but only of one period. At Florence, which is his

birthplace, you can see pictures by him of every date, and

every kind. But you had surely better see, first, what is of

his best time and of the best kind. He painted very small

pictures and very large—painted from the age of twelve to

sixty—painted some subjects carelessly which he had little

interest in—some carefully with all his heart. You would

surely like, and it would certainly be wise, to see him first

in his strong and earnest work,—to see a painting by him, if

possible, of large size, and wrought with his full strength,

and of a subject pleasing to him. And if it were, also, a

subject interesting to yourself,—better still.

2. Now, if indeed you

are interested in old art, you cannot but know the power of

the thirteenth century. You know that the character of it was

concentrated in, and to the full expressed by, its best king,

St. Louis. You know St. Louis was a Franciscan, and that the

Franciscans, for whom Giotto was continually painting under

Dante's advice, were prouder of him than of any other of their

royal brethren or sisters. If Giotto ever would imagine

anybody with care and delight, it would be St. Louis, if it

chanced that anywhere he had St. Louis to paint.

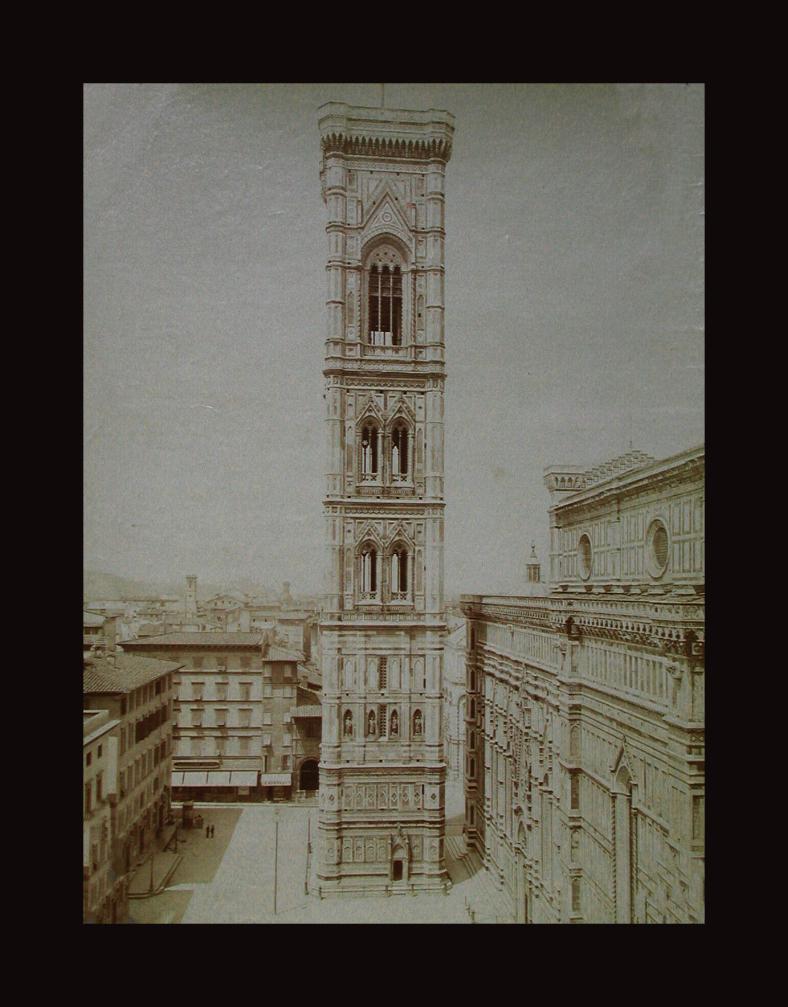

Also, you know that he

was appointed to build the Campanile of the Duomo, because he

was then the best master of sculpture, painting, and

architecture in Florence, and supposed to be without superior

in the world.1

And that this commission

was given him late in life (of course he could not have

designed the Campanile when he was a boy); so therefore, if

you find any of his figures niched under pure campanile

architecture, and the architecture by his hand, you know,

without other evidence, that the painting must be of his

strongest time.

So if one wanted to find

anything of his to begin with, especially, and could choose

what it should be, one would say, "A fresco, life size, with

campanile architecture behind it, painted in an important

place; and if one might choose one's subject, perhaps the most

interesting saint of all saints—for him to do for us—would be

St. Louis."

3. Wait then for an

entirely bright morning; rise with the sun, and go to Santa

Croce, with a good opera-glass in your pocket, with which you

shall for once, at any rate, see an "opus"; and, if you have

time, several opera. Walk straight to the chapel on the right

of the choir ("k" in your Murray's guide). When you first get

into it, you will see nothing but a modern window of glaring

glass, with a red-hot cardinal in one pane—which piece of

modern manufacture takes away at least seven-eighths of the

light (little enough before) by which you might have seen what

is worth sight. Wait patiently till you get used to the gloom.

Then, guarding your eyes from the accursed modern window as

best you may, take your opera-glass and look to the right, at

the uppermost of the two figures beside it. It is St. Louis,

under campanile architecture, painted by—Giotto? or the last

Florentine painter who wanted a job—over Giotto? That is the

first question you have to determine; as you will have

henceforward, in every case in which you look at a fresco.

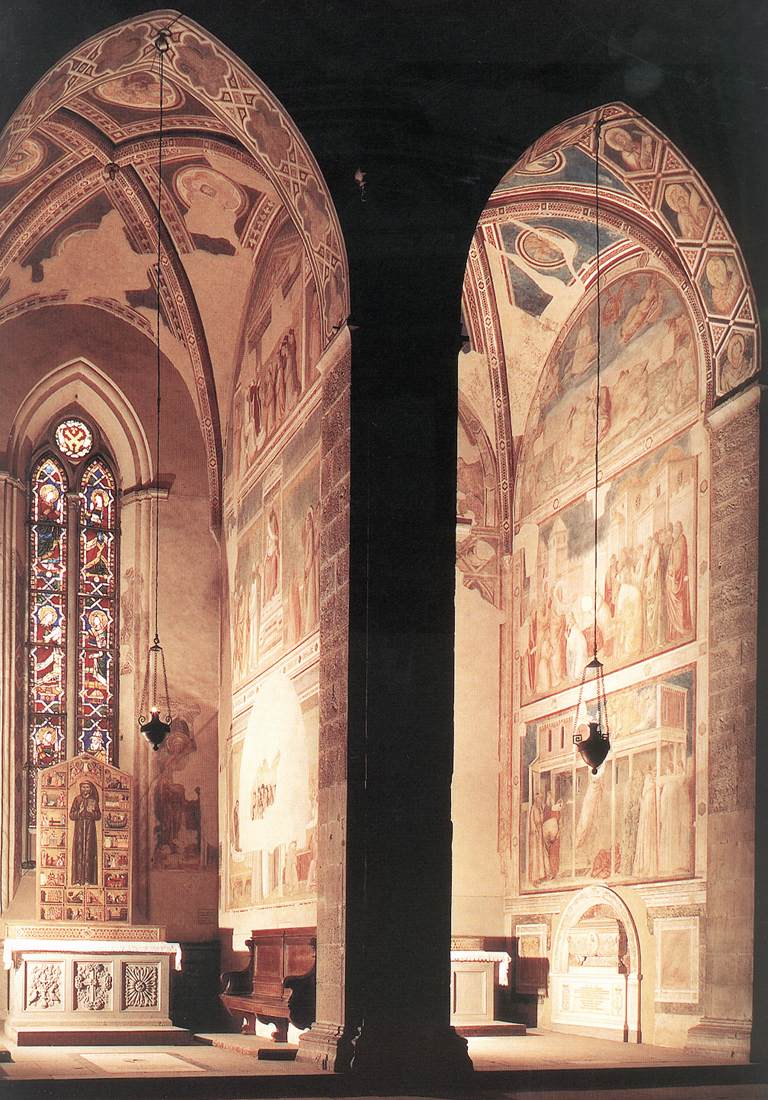

Santa Croce, Capella de' Bardi

St Louis, King of France, top right, no longer exists

Sometimes there will be

no question at all. These two grey frescos at the bottom of

the walls on the right and left, for instance, have been

entirely got up for your better satisfaction, in the last year

or two—over Giotto's half-effaced lines. But that St. Louis?

Re-painted or not, it is a lovely thing,—there can be no

question about that; and we must look at it, after some

preliminary knowledge gained, not inattentively.

4. Your Murray's Guide

tells you that this chapel of the Bardi della Libertà, in

which you stand, is covered with frescos by Giotto; that they

were whitewashed, and only laid bare in 1853; that they were

painted between 1296 and 1304; that they represent scenes in

the life of St. Francis; and that on each side of the window

are paintings of St. Louis of Toulouse, St. Louis king of

France, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, and St. Claire,—"all much

restored and repainted." Under such recommendation, the

frescos are not likely to be much sought after; and

accordingly, as I was at work in the chapel this morning,

Sunday, 6th September, 1874, two nice-looking Englishmen,

under guard of their valet de place, passed the chapel without

so much as looking in.

You will perhaps stay a

little longer in it with me, good reader, and find out

gradually where you are. Namely, in the most interesting and

perfect little Gothic chapel in all Italy—so far as I know or

can hear. There is no other of the great time which has all

its frescos in their place. The Arena, though far larger, is

of earlier date—not pure Gothic, nor showing Giotto's full

force. The lower chapel at Assisi is not Gothic at all, and is

still only of Giotto's middle time. You have here, developed

Gothic, with Giotto in his consummate strength, and nothing

lost, in form, of the complete design.

By restoration—judicious

restoration, as Mr. Murray usually calls it—there is no saying

how much you have lost, Putting the question of restoration

out of your mind, however, for a while, think where you are,

and what you have got to look at.

5. You are in the chapel

next the high altar of the great Franciscan church of

Florence. A few hundred yards west of you, within ten minutes'

walk, is the Baptistery of Florence. And five minutes' walk

west of that is the great Dominican church of Florence, Santa

Maria Novella.

1807. Firenze. Il

Battistero (Dal VII e VIII secolo, restaurato e rivestito di

marmi di Arnolfo di Cambio)

For larger image, click here

On Back: '5551. Firenze. Chiesa e Piazza di S.

Maria Novella. Edit. Brunner & C., Como, Stab.

eliografico'.

For larger image, click here

Get this little bit of

geography, and architectural fact, well into your mind. There

is the little octagon Baptistery in the middle; here, ten

minutes' walk east of it, the Franciscan church of the Holy

Cross; there, five minutes walk west of it, the Dominican

church of St. Mary.

Now, that little octagon

Baptistery stood where it now stands (and was finished, though

the roof has been altered since) in the eighth century. It is

the central building of Etrurian Christianity,—of European

Christianity.

From the day it was

finished, Christianity went on doing her best, in Etruria and

elsewhere, for four hundred years,—and her best seemed to have

come to very little,—when there rose up two men who vowed to

God it should come to more. And they made it come to more,

forthwith; of which the immediate sign in Florence was that

she resolved to have a fine new cross-shaped cathedral instead

of her quaint old little octagon one; and a tower beside it

that should beat Babel:—which two buildings you have also

within sight.

6. But your business is

not at present with them; but with these two earlier churches

of Holy Cross and St. Mary. The two men who were the effectual

builders of these were the two great religious Powers and

Reformers of the thirteenth century;—St. Francis, who taught

Christian men how they should behave, and St. Dominic, who

taught Christian men what they should think. In brief, one the

Apostle of Works; the other of Faith. Each sent his little

company of disciples to teach and to preach in Florence: St.

Francis in 1212; St. Dominic in 1220.

The little companies

were settled—one, ten minutes' walk east of the old

Baptistery; the other five minutes' walk west of it. And after

they had stayed quietly in such lodgings as were given them,

preaching and teaching through most of the century; and had

got Florence, as it were, heated through, she burst out into

Christian poetry and architecture, of which you have heard

much talk:—burst into bloom of Arnolfo, Giotto, Dante,

Orcagna, and the like persons, whose works you profess to have

come to Florence that you may see and understand.

Florence then, thus

heated through, first helped her teachers to build finer

churches. The Dominicans, or White Friars the Teachers of

Faith, began their church of St. Mary's in 1279. The

Franciscans, or Black Friars, the teachers of Works, laid the

first stone of this church of the Holy Cross in 1294. And the

whole city laid the foundations of its new cathedral in 1298.

The Dominicans designed their own building; but for the

Franciscans and the town worked the first great master of

Gothic art, Arnolfo; with Giotto at his side, and Dante

looking on, and whispering sometimes a word to both.

7. And here you stand

beside the high altar of the Franciscans' church, under a

vault of Arnolfo's building, with at least some of Giotto's

colour on it still fresh; and in front of you, over the little

altar, is the only reportedly authentic portrait of St.

Francis, taken from life by Giotto's master. Yet I can hardly

blame my two English friends for never looking in. Except in

the early morning light, not one touch of all this art can be

seen. And in any light, unless you understand the relations of

Giotto to St. Francis, and of St. Francis to humanity, it will

be of little interest.

Observe, then, the

special character of Giotto among the great painters of Italy

is his being a practical person. Whatever other men dreamed

of, he did. He could work in mosaic; he could work in marble;

he could paint; and he could build; and all thoroughly: a man

of supreme faculty, supreme common sense. Accordingly, he

ranges himself at once among the disciples of the Apostle of

Works, and spends most of his time in the same apostleship.

Now the gospel of Works,

according to St. Francis, lay in three things. You must work

without money, and be poor. You must work without pleasure,

and be chaste. You must work according to orders, and be

obedient.

Those are St. Francis's

three articles of Italian opera. By which grew the many pretty

things you have come to see here.

Bardi Chapel, fresco of St Louis, King of

France, lost, also most of vault frescoes

8. And now if you will

take your opera-glass and look up to the roof above Arnolfo's

building, you will see it is a pretty Gothic cross vault, in

four quarters, each with a circular medallion, painted by

Giotto. That over the altar has the picture of St. Francis

himself. The three others, of his Commanding Angels. In front

of him, over the entrance arch, Poverty. On his right hand,

Obedience. On his left, Chastity.

Poverty, in a red

patched dress, with grey wings, and a square nimbus of glory

above her head, is flying from a black hound, whose head is

seen at the corner of the medallion.

Chastity, veiled, is

imprisoned in a tower, while angels watch her.

Obedience bears a yoke

on her shoulders, and lays her hand on a book.

Now, this same

quatrefoil, of St. Francis and his three Commanding Angels,

was also painted, but much more elaborately, by Giotto, on the

cross vault of the lower church of Assisi, and it is a

question of interest which of the two roofs was painted first.

Your Murray's Guide

tells you the frescos in this chapel were painted between 1296

and 1304. But as they represent, among other personages, St.

Louis of Toulouse, who was not canonized till 1317, that

statement is not altogether tenable. Also, as the first stone

of the church was only laid in 1294, when Giotto was a youth

of eighteen, it is little likely that either it would have

been ready to be painted, or he ready with his scheme of

practical divinity, two years later.

Farther, Arnolfo, the

builder of the main body of the church, died in 1310. And as

St. Louis of Toulouse was not a saint till seven years

afterwards, and the frescoes therefore beside the window not

painted in Arnolfo's day, it becomes another question whether

Arnolfo left the chapels or the church at all, in their

present form.

9. On which point—now

that I have shown you where Giotto's St. Louis is—I will ask

you to think awhile, until you are interested; and then I will

try to satisfy your curiosity. Therefore, please leave the

little chapel for the moment, and walk down the nave, till you

come to two sepulchral slabs near the west end, and then look

about you and see what sort of a church Santa Croce is.

Without looking about

you at all, you may find, in your Murray, the useful

information that it is a church which "consists of a very wide

nave and lateral aisles, separated by seven fine pointed

arches." And as you will be—under ordinary conditions of

tourist hurry—glad to learn so much, without looking,

it is little likely to occur to you that this nave and two

rich aisles required also, for your complete present comfort,

walls at both ends, and a roof on the top. It is just

possible, indeed, you may have been struck, on entering, by

the curious disposition of painted glass at the east end;—more

remotely possible that, in returning down the nave, you may

this moment have noticed the extremely small circular window

at the west end; but the chances are a thousand to one that,

after being pulled from tomb to tomb round the aisles and

chapels, you should take so extraordinary an additional amount

of pains as to look up at the roof,—unless you do it now,

quietly. It will have had its effect upon you, even if you

don't, without your knowledge. You will return home with a

general impression that Santa Croce is, somehow, the ugliest

Gothic church you ever were in. Well, that is really so; and

now, will you take the pains to see why?

10. There are two

features, on which, more than on any others, the grace and

delight of a fine Gothic building depends; one is the

springing of its vaultings, the other the proportion and

fantasy of its traceries. This church of Santa Croce

has no vaultings at all, but the roof of a farm-house barn.

And its windows are all of the same pattern,—the exceedingly

prosaic one of two pointed arches, with a round hole above,

between them.

And to make the

simplicity of the roof more conspicuous, the aisles are

successive sheds, built at every arch. In the aisles of the

Campo Santo of Pisa, the unbroken flat roof leaves the eye

free to look to the traceries; but here, a succession of

up-and-down sloping beam and lath gives the impression of a

line of stabling rather than a church aisle. And lastly,

while, in fine Gothic buildings, the entire perspective

concludes itself gloriously in the high and distant apse, here

the nave is cut across sharply by a line of ten chapels, the

apse being only a tall recess in the midst of them, so that,

strictly speaking, the church is not of the form of a cross,

but of a letter T.

Can this clumsy and

ungraceful arrangement be indeed the design of the renowned

Arnolfo?

Yes, this is purest

Arnolfo-Gothic; not beautiful by any means; but deserving,

nevertheless, our thoughtfullest examination. We will trace

its complete character another day; just now we are only

concerned with this pre-Christian form of the letter T,

insisted upon in the lines of chapels.

11. Respecting which you

are to observe, that the first Christian churches in the

catacombs took the form of a blunt cross naturally; a square

chamber having a vaulted recess on each side; then the

Byzantine churches were structurally built in the form of an

equal cross; while the heraldic and other ornamental

equal-armed crosses are partly signs of glory and victory,

partly of light, and divine spiritual presence.2

But the Franciscans and

Dominicans saw in the cross no sign of triumph, but of trial.3 The wounds of their Master were to be

their inheritance. So their first aim was to make what image

to the cross their church might present, distinctly that of

the actual instrument of death.

And they did this most

effectually by using the form of the letter T, that of the

Furca or Gibbet,—not the sign of peace.

Also, their churches

were meant for use; not show, nor self-glorification, nor

town-glorification. They wanted places for preaching, prayer,

sacrifice, burial; and had no intention of showing how high

they could build towers, or how widely they could arch vaults.

Strong walls, and the roof of a barn,—these your Franciscan

asks of his Arnolfo. These Arnolfo gives,—thoroughly and

wisely built; the successions of gable roof being a new device

for strength, much praised in its day.

12. This stern humor did

not last long. Arnolfo himself had other notions; much more

Cimabue and Giotto; most of all, Nature and Heaven. Something

else had to be taught about Christ than that He was wounded to

death. Nevertheless, look how grand this stern form would be,

restored to its simplicity. It is not the old church which is

in itself unimpressive. It is the old church defaced by

Vasari, by Michael Angelo, and by modern Florence. See those

huge tombs on your right hand and left, at the sides of the

aisles, with their alternate gable and round tops, and their

paltriest of all possible sculpture, trying to be grand by

bigness, and pathetic by expense. Tear them all down in your

imagination; fancy the vast hall with its massive pillars,—not

painted calomel-pill colour, as now, but of their native

stone, with a rough, true wood for roof,—and a people praying

beneath them, strong in abiding, and pure in life, as their

rocks and olive forests That was Arnolfo's Santa Croce. Nor

did his work remain long without grace.

That very line of

chapels in which we found our St. Louis shows signs of change

in temper. They have no pent-house roofs, but true

Gothic vaults: we found our four-square type of Franciscan Law

on one of them.

It is probable, then,

that these chapels may be later than the rest—even in their

stonework. In their decoration, they are so, assuredly;

belonging already to the time when the story of St. Francis

was becoming a passionate tradition, told and painted

everywhere with delight.

And that high recess,

taking the place of apse, in the centre,—see how noble it is

in the coloured shade surrounding and joining the glow of its

windows, though their form be so simple. You are not to be

amused here by patterns in balanced stone, as a French or

English architect would amuse you, says Arnolfo. "You are to

read and think, under these severe walls of mine; immortal

hands will write upon them." We will go back, therefore, into

this line of manuscript chapels presently; but first, look at

the two sepulchral slabs by which you are standing. That

farther of the two from the west end is one of the most

beautiful pieces of fourteenth century sculpture in this

world; and it contains simple elements of excellence, by your

understanding of which you may test your power of

understanding the more difficult ones you will have to deal

with presently.

13. It represents an old

man, in the high deeply-folded cap worn by scholars and

gentlemen in Florence from 1300—1500, lying dead, with a book

in his breast, over which his hands are folded. At his feet is

this inscription: "Temporibus hic suis phylosophye atq.

medicine culmen fuit Galileus de Galileis olim Bonajutis qui

etiam summo in magistratu miro quodam modo rempublicam

dilexit, cujus sancte memorie bene acte vite pie benedictus

filius hunc tumulum patri sibi suisq. posteris edidit."

Mr. Murray tells you

that the effigies "in low relief" (alas, yes, low enough

now—worn mostly into flat stones, with a trace only of the

deeper lines left, but originally in very bold relief,) with

which the floor of Santa Croce is inlaid, of which this by

which you stand is characteristic, are "interesting from the

costume," but that, "except in the case of John Ketterick,

Bishop of St. David's, few of the other names have any

interest beyond the walls of Florence." As, however, you are

at present within the walls of Florence, you may perhaps

condescend to take some interest in this ancestor or relation

of the Galileo whom Florence indeed left to be externally

interesting, and would not allow to enter in her walls.4

I am not sure if I

rightly place or construe the phrase in the above inscription,

"cujus sancte memorie bene acte;" but, in main purport, the

legend runs thus: "This Galileo of the Galilei was, in his

times, the head of philosophy and medicine; who also in the

highest magistracy loved the republic marvellously; whose son,

blessed in inheritance of his holy memory and well-passed and

pious life, appointed this tomb for his father, for himself,

and for his posterity."

There is no date; but

the slab immediately behind it, nearer the western door, is of

the same style, but of later and inferior work, and bears

date—I forget now of what early year in the fifteenth century.

But Florence was still

in her pride; and you may observe, in this epitaph, on what it

was based. That her philosophy was studied together with

useful arts, and as a part of them; that the masters in

these became naturally the masters in public affairs; that in

such magistracy, they loved the State, and neither cringed to

it nor robbed it; that the sons honoured their fathers, and

received their fathers' honour as the most blessed

inheritance. Remember the phrase "vite pie bene dictus

filius," to be compared with the "nos nequiores" of the

declining days of all states,—chiefly now in Florence, France

and England.

14. Thus much for the

local interest of name. Next for the universal interest of the

art of this tomb.

It is the crowning

virtue of all great art that, however little is left of it by

the injuries of time, that little will be lovely. As long as

you can see anything, you can see—almost all;—so much the hand

of the master will suggest of his soul.

And here you are well

quit, for once, of restoration. No one cares for this

sculpture; and if Florence would only thus put all her old

sculpture and painting under her feet, and simply use them for

gravestones and oilcloth, she would be more merciful to them

than she is now. Here, at least, what little is left is true.

And, if you look long,

you will find it is not so little. That worn face is still a

perfect portrait of the old man, though like one struck out at

a venture, with a few rough touches of a master's chisel. And

that falling drapery of his cap is, in its few lines,

faultless, and subtle beyond description.

And now, here is a

simple but most useful test of your capacity for understanding

Florentine sculpture or painting. If you can see that the

lines of that cap are both right, and lovely; that the choice

of the folds is exquisite in its ornamental relations of line;

and that the softness and ease of them is complete,—though

only sketched with a few dark touches,—then you can understand

Giotto's drawing, and Botticelli's;—Donatello's carving and

Luca's. But if you see nothing in this sculpture, you

will see nothing in theirs, of theirs. Where they

choose to imitate flesh, or silk, or to play any vulgar modern

trick with marble—(and they often do)—whatever, in a word, is

French, or American, or Cockney, in their work, you can see;

but what is Florentine, and for ever great—unless you can see

also the beauty of this old man in his citizen's cap,—you will

see never.

15. There is more in

this sculpture, however, than its simple portraiture and noble

drapery. The old man lies on a piece of embroidered carpet;

and, protected by the higher relief, many of the finer lines

of this are almost uninjured; in particular, its

exquisitely-wrought fringe and tassels are nearly perfect. And

if you will kneel down and look long at the tassels of the

cushion under the head, and the way they fill the angles of

the stone, you will,—or may—know, from this example alone,

what noble decorative sculpture is, and was, and must be, from

the days of earliest Greece to those of latest Italy.

"Exquisitely sculptured

fringe!" and you have just been abusing sculptors who play

tricks with marble! Yes, and you cannot find a better example,

in all the museums of Europe, of the work of a man who does not

play tricks with it—than this tomb. Try to understand the

difference: it is a point of quite cardinal importance to all

your future study of sculpture.

I told you,

observe, that the old Galileo was lying on a piece of

embroidered carpet. I don't think, if I had not told you, that

you would have found it out for yourself. It is not so like a

carpet as all that comes to.

But had it been a modern

trick-sculpture, the moment you came to the tomb you would

have said, "Dear me! how wonderfully that carpet is done,—it

doesn't look like stone in the least—one longs to take it up

and beat it, to get the dust off."

Now whenever you feel

inclined to speak so of a sculptured drapery, be assured,

without more ado, the sculpture is base, and bad. You will

merely waste your time and corrupt your taste by looking at

it. Nothing is so easy as to imitate drapery in marble. You

may cast a piece any day; and carve it with such subtlety that

the marble shall be an absolute image of the folds. But that

is not sculpture. That is mechanical manufacture.

No great sculptor, from

the beginning of art to the end of it, has ever carved, or

ever will, a deceptive drapery. He has neither time nor will

to do it. His mason's lad may do that if he likes. A man who

can carve a limb or a face never finishes inferior parts, but

either with a hasty and scornful chisel, or with such grave

and strict selection of their lines as you know at once to be

imaginative, not imitative.

16. But if, as in this

case, he wants to oppose the simplicity of his central subject

with a rich background,—a labyrinth of ornamental lines to

relieve the severity of expressive ones,—he will carve you a

carpet, or a tree, or a rose thicket, with their fringes and

leaves and thorns, elaborated as richly as natural ones; but

always for the sake of the ornamental form, never of the

imitation; yet, seizing the natural character in the lines he

gives, with twenty times the precision and clearness of sight

that the mere imitator has. Examine the tassels of the

cushion, and the way they blend with the fringe, thoroughly;

you cannot possibly see finer ornamental sculpture. Then, look

at the same tassels in the same place of the slab next the

west end of the church, and you will see a scholar's rude

imitation of a master's hand, though in a fine school.

(Notice, however, the folds of the drapery at the feet of this

figure: they are cut so as to show the hem of the robe within

as well as without, and are fine.) Then, as you go back to

Giotto's chapel, keep to the left, and just beyond the north

door in the aisle is the much celebrated tomb of C.

Marsuppini, by Desiderio of Settignano. It is very fine of its

kind; but there the drapery is chiefly done to cheat you, and

chased delicately to show how finely the sculptor could chisel

it. It is wholly vulgar and mean in cast of fold. Under your

feet, as you look at it, you will tread another tomb of the

fine time, which, looking last at, you will recognize the

difference between the false and true art, as far as there is

capacity in you at present to do so. And if you really and

honestly like the low-lying stones, and see more beauty in

them, you have also the power of enjoying Giotto, into whose

chapel we will return to-morrow;—not to-day, for the light

must have left it by this time; and now that you have been

looking at these sculptures on the floor you had better

traverse nave and aisle across and across; and get some idea

of that sacred field of stone. In the north transept you will

find a beautiful knight, the finest in chiselling of all these

tombs, except one by the same hand in the south aisle just

where it enters the south transept.

2111. Firenze. Chiesa di S. Croce. Monumento a Carlo

Marsuppini. (Desiderio da Settignano)

For larger image, click here

Examine the lines of the

Gothic niches traced above them; and what is left of arabesque

on their armour. They are far more beautiful and tender in

chivalric conception than Donatello's St. George, which is

merely a piece of vigorous naturalism founded on these older

tombs. If you will drive in the evening to the Chartreuse in

Val d'Ema, you may see there an uninjured example of this

slab-tomb by Donatello himself; very beautiful; but not so

perfect as the earlier ones on which it is founded. And you

may see some fading light and shade of monastic life, among

which if you stay till the fireflies come out in the twilight,

and thus get to sleep when you come home, you will be better

prepared for to-morrow morning's walk—if you will take another

with me—than if you go to a party, to talk sentiment about

Italy, and hear the last news from London and New York.

2812 Firenze S. Museo Nazionale S. Giorgio

For larger image, click here

Augustus Hare, Florence

4097 Firenze. Contorni.

Certosa. Chiostro

For larger image, click here

1· · "Cum

in

universe orbe non reperiri dicatur quenquam qui sufficientior

sit in his et aliis multis artibus magistro Giotto Bondonis de

Florentia, pictore, et accipiendus sit in patriâ, velut magnus

magister."—(Decree of his appointment, quoted by Lord Lindsay,

vol. ii., p. 247.)

2· · See,

on this subject generally, Mr. R. St. J. Tyrwhitt's

"Art-Teaching of the Primitive Church." S. P. B. K., 1874.

3· · I

have never obtained time for any right study of early

Christian church-discipline,—nor am I sure to how many other

causes, the choice of the form of the basilica may be

occasionally attributed, or by what other communities it may

be made. Symbolism, for instance, has most power with the

Franciscans, and convenience for preaching with the

Dominicans; but in all cases, and in all places, the

transition from the close tribune to the brightly-lighted

apse, indicates the change in Christian feeling between

regarding a church as a place for public judgment or teaching,

or a place for private prayer and congregational praise. The

following passage from the Dean of Westminster's perfect

history of his Abbey ought to be read also in the Florentine

church:—"The nearest approach to Westminster Abbey in this

aspect is the church of Santa Croce at Florence. There, as

here, the present destination of the building was no part of

the original design, but was the result of various converging

causes. As the church of one of the two great preaching

orders, it had a nave large beyond all proportion to its

choir. That order being the Franciscan, bound by vows of

poverty, the simplicity of the worship preserved the whole

space clear from any adventitious ornaments. The popularity of

the Franciscans, especially in a convent hallowed by a visit

from St. Francis himself, drew to it not only the chief civic

festivals, but also the numerous families who gave alms to the

friars, and whose connection with their church was, for this

reason, in turn encouraged by them. In those graves, piled

with standards und achievements of the noble families of

Florence, were successively interred—not because of their

eminence, but as members or friends of those families—some of

the most illustrious personages of the fifteenth century. Thus

it came to pass, as if by accident, that in the vault of the

Buonarotti was laid Michael Angelo; in the vault of the

Viviani the preceptor of one of their house, Galileo. From

those two burials the church gradually be came the recognized

shrine of Italian genius."

· "Seven years a

prisoner at the city gate,

Let

in but his grave-clothes."

Rogers'

"Italy."

GO

TO SECOND

MORNING

FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA