FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

JOHN RUSKIN

MORNINGS IN FLORENCE VI

THE SIXTH MORNING

THE SHEPHERD'S TOWER

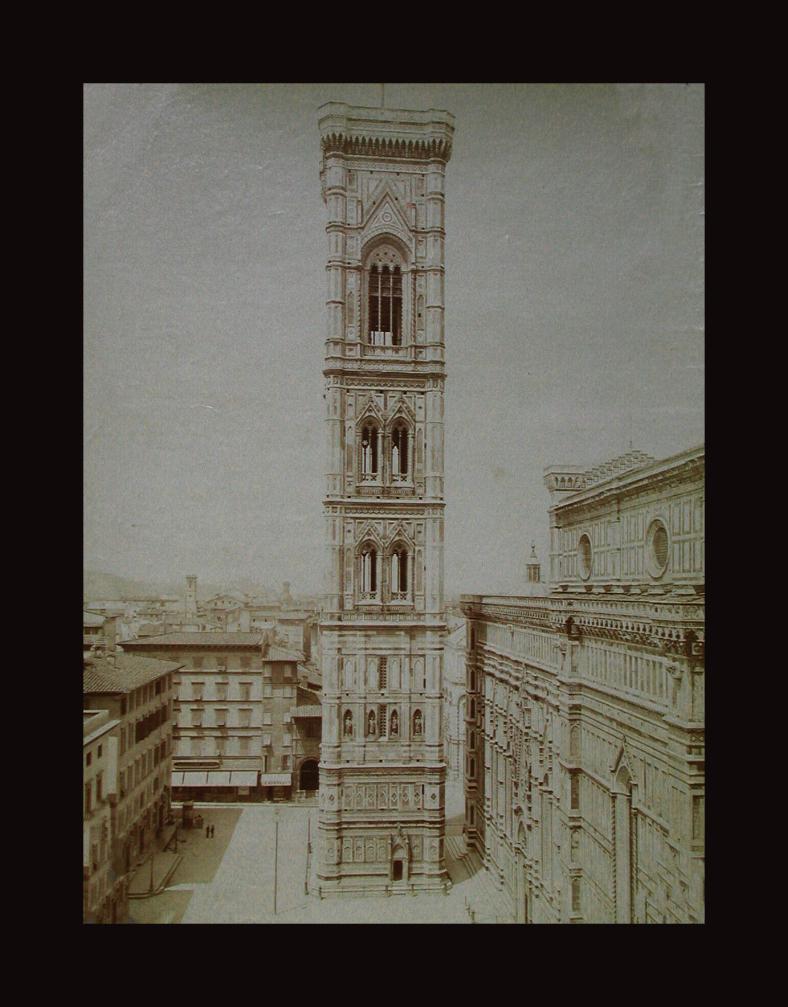

[Giotto,

Campanile, Allegory of Skills and Education]

AM obliged to interrupt my account of the

Spanish chapel by the following notes on the sculptures of

Giotto's Campanile: first because I find that inaccurate

accounts of those sculptures are in course of publication; and

chiefly because I cannot finish my work in the Spanish chapel

until one of my good Oxford helpers, Mr. Caird, has completed

some investigations he has undertaken for me upon the history

connected with it. I had written my own analysis of the fourth

side, believing that in every scene of it the figure of St.

Dominic was repeated. Mr. Caird first suggested, and has shown

me already good grounds for his belief.1 that the preaching

monks represented are in each scene intended for a different

person. I am informed also of several careless mistakes which

have got into my description of the fresco of the Sciences;

and finally, another of my young helpers, Mr. Charles F.

Murray,—one, however, whose help is given much in the form of

antagonism,—informs me of various critical discoveries lately

made, both by himself, and by industrious Germans, of points

respecting the authenticity of this and that, which will

require notice from me: more especially he tells me of

certification that the picture in the Uffizi, of which I

accepted the ordinary attribution to Giotto, is by Lorenzo

Monaco,—which indeed may well be, without in the least

diminishing the use to you of what I have written of its

predella, and without in the least, if you think rightly of

the matter, diminishing your confidence in what I tell you of

Giotto generally. There is one kind of knowledge of pictures

which is the artist's, and another which is the antiquary's

and the picture-dealer's; the latter especially acute, and

founded on very secure and wide knowledge of canvas, pigment,

and tricks of touch, without, necessarily, involving any

knowledge whatever of the qualities of art itself. There are

few practised dealers in the great cities of Europe whose

opinion would not be more trustworthy than mine, (if you could

get it, mind you,) on points of actual authenticity.

But they could only tell you whether the picture was by such

and such a master, and not at all what either the master or

his work were good for. Thus, I have, before now, taken

drawings by Varley and by Cousins for early studies by Turner,

and have been convinced by the dealers that they knew better

than I, as far as regarded the authenticity of those drawings;

but the dealers don't know Turner, or the worth of him, so

well as I, for all that. So also, you may find me again and

again mistaken among the much more confused work of the early

Giottesque schools, as to the authenticity of this work or the

other; but you will find (and I say it with far more sorrow

than pride) that I am simply the only person who can at

present tell you the real worth of any; you will find

that whenever I tell you to look at a picture, it is worth

your pains; and whenever I tell you the character of a

painter, that it is his character, discerned by me

faithfully in spite of all confusion of work falsely

attributed to him in which similar character may exist. Thus,

when I mistook Cousins for Turner, I was looking at a piece of

subtlety in the sky of which the dealer had no consciousness

whatever, which was essentially Turneresque, but which another

man might sometimes equal; whereas the dealer might be only

looking at the quality of Whatman's paper, which Cousins used,

and Turner did not.

119.Not, in the

meanwhile, to leave you quite guideless as to the main subject

of the fourth fresco in the Spanish chapel,—the Pilgrim's

Progress of Florence,—here is a brief map of it:

On the right, in lowest

angle, St. Dominic preaches to the group of Infidels; in the

next group towards the left, he (or some one very like him)

preaches to the Heretics: the Heretics proving obstinate, he

sets his dogs at them, as at the fatallest of wolves, who

being driven away, the rescued lambs are gathered at the feet

of the Pope. I have copied the head of the very pious, but

slightly weak-minded, little lamb in the centre, to compare

with my rough Cumberland ones, who have had no such grave

experiences. The whole group, with the Pope above, (the niche

of the Duomo joining with and enriching the decorative power

of his mitre,) is a quite delicious piece of design.

The Church being thus

pacified, is seen in worldly honour under the powers of the

Spiritual and Temporal Rulers. The Pope, with Cardinal and

Bishop descending in order on his right; the Emperor, with

King and Baron descending in order on his left; the

ecclesiastical body of the whole Church on the right side, and

the laity,—chiefly its poets and artists, on the left.

Then, the redeemed

Church nevertheless giving itself up to the vanities and

temptations of the world, its forgetful saints are seen

feasting, with their children dancing before them, (the Seven

Mortal Sins, say some commentators). But the wise-hearted of

them confess their sins to another ghost of St. Dominic; and

confessed, becoming as little children, enter hand in hand the

gate of the Eternal Paradise, crowned with flowers by the

waiting angels, and admitted by St. Peter among the serenely

joyful crowd of all the saints, above whom the white Madonna

stands reverently before the throne. There is, so far as I

know, throughout all the schools of Christian art, no other so

perfect statement of the noble policy and religion of men.

120. I had intended to

give the best account of it in my power; but, when at

Florence, lost all time for writing that I might copy the

group of the Pope and Emperor for the schools of Oxford; and

the work since done by Mr. Caird has informed me of so much,

and given me, in some of its suggestions, so much to think of,

that I believe it will be best and most just to print at once

his account of the fresco as a supplement to these essays of

mine, merely indicating any points on which I have objections

to raise, and so leave matters till Fors lets me see Florence

once more.

Perhaps she may, in

kindness forbid my ever seeing it more, the wreck of it being

now too ghastly and heartbreaking to any human soul that

remembers the days of old. Forty years ago, there was

assuredly no spot of ground, out of Palestine, in all the

round world, on which, if you knew, even but a little, the

true course of that world's history, you saw with so much

joyful reverence the dawn of morning, as at the foot of the

Tower of Giotto. For there the traditions of faith and hope,

of both the Gentile and Jewish races, met for their beautiful

labour: the Baptistery of Florence is the last building raised

on the earth by the descendants of the workmen taught by

Dædalus: and the Tower of Giotto is the loveliest of those

raised on earth under the inspiration of the men who lifted up

the tabernacle in the wilderness. Of living Greek work there

is none after the Florentine Baptistery; of living Christian

work, none so perfect as the Tower of Giotto; and, under the

gleam and shadow of their marbles, the morning light was

haunted by the ghosts of the Father of Natural Science,

Galileo; of Sacred Art, Angelico, and the Master of Sacred

Song. Which spot of ground the modern Florentine has made his

principal hackney-coach stand and omnibus station. The hackney

coaches, with their more or less farmyard-like litter of

occasional hay, and smell of variously mixed horse-manure, are

yet in more permissible harmony with the place than the

ordinary populace of a fashionable promenade would be, with

its cigars, spitting, and harlot- planned fineries: but the

omnibus place of call being in front of the door of the tower,

renders it impossible to stand for a moment near it, to look

at the sculptures either of the eastern or southern side;

while the north side is enclosed with an iron railing, and

usually encumbered with lumber as well: not a soul in Florence

ever caring now for sight of any piece of its old artists'

work; and the mass of strangers being on the whole intent on

nothing but getting the omnibus to go by steam; and so seeing

the cathedral in one swift circuit, by glimpses between the

puffs of it.

1807.

Firenze. Il Battistero (Dal VII e VIII secolo, restaurato

e rivestito di marmi di Arnolfo di Cambio)

For larger image, click here

1993.

Firenze. Cattedrale. Il Campanile (Giotto)

For larger image, click here

121. The front of Notre

Dame of Paris was similarly turned into a coach-office when I

last saw it—1872.2 Within

fifty yards of me as I write, the Oratory of the Holy Ghost is

used for a tobacco-store, and in fine, over all Europe, mere

Caliban bestiality and Satyric ravage staggering, drunk and

desperate, into every once enchanted cell where the prosperity

of kingdoms ruled and the miraculous- ness of beauty was

shrined in peace.

Deluge of profanity,

drowning dome and tower in Stygian pool of vilest

thought,—nothing now left sacred, in the places where

once—nothing was profane.

For that is

indeed the teaching, if you could receive it, of the Tower of

Giotto; as of all Christian art in its day. Next to

declaration of the facts of the Gospel, its purpose, (often in

actual work the eagerest,) was to show the power of

the Gospel. History of Christ in due place; yes, history of

all He did, and how He died: but then, and often, as I say,

with more animated imagination, the showing of His risen

presence in granting the harvests and guiding the labour of

the year. All sun and rain, and length or decline of days

received from His hand; all joy, and grief, and strength, or

cessation of labour, indulged or endured, as in His sight and

to His glory. And the familiar employments of the seasons, the

homely toils of the peasant, the lowliest skills of the

craftsman, are signed always on the stones of the Church, as

the first and truest condition of sacrifice and offering.

122. Of these

representations of human art under heavenly guidance, the

series of bas-reliefs which stud the base of this tower of

Giotto's must be held certainly the chief in Europe.3 At first you may be

surprised at the smallness of their scale in proportion to

their masonry; but this smallness of scale enabled the master

workmen of the tower to execute them with their own hands; and

for the rest, in the very finest architecture, the decoration

of most precious kind is usually thought of as a jewel, and

set with space round it,—as the jewels of a crown, or the

clasp of a girdle. It is in general not possible for a great

workman to carve, himself, a greatly conspicuous series of

ornament; nay, even his energy fails him in design, when the

bas-relief extends itself into incrustation, or involves the

treatment of great masses of stone. If his own does not, the

spectator's will. It would be the work of a long summer's day

to examine the over-loaded sculptures of the Certosa of Pavia;

and yet in the tired last hour, you would be empty-hearted.

Read but these inlaid jewels of Giotto's once with patient

following; and your hour's study will give you strength for

all your life. So far as you can, examine them of course on

the spot; but to know them thoroughly you must have their

photographs: the subdued colour of the old marble fortunately

keeps the lights subdued, so that the photograph may be made

more tender in the shadows than is usual in its renderings of

sculpture, and there are few pieces of art which may now be so

well known as these, in quiet homes far away.

123. We begin on the

western side. There are seven sculptures on the western,

southern, and northern sides: six on the eastern; counting the

Lamb over the entrance door of the tower, which divides the

complete series into two groups of eighteen and eight. Itself,

between them, being the introduction to the following eight,

you must count it as the first of the terminal group; you then

have the whole twenty-seven sculptures divided into eighteen

and nine.

Thus lettering the

groups on each side for West, South, East, and North, we have:

W. S. E. N.

7 + 7 + 6 + 7 = 27; or,

W. S. E.

7 + 7 + 4

= 18; and,

E. N.

2 + 7 = 9

There is a very special

reason for this division by nines but, for convenience' sake,

I shall number the whole from 1 to 27, straightforwardly. And

if you will have patience with me, I should like to go round

the tower once and again; first observing the general meaning

and connection of the subjects and then going back to examine

the technical points in each, and such minor specialties as it

may be well, at the first time, to pass over.

124. (1). The series

begins, then, on the west side, with the Creation of Man. It

is not the beginning of the story of Genesis; but the simple

assertion that God made us, and breathed, and still breathes,

into our nostrils the breath of life.

This, Giotto tells you

to believe as the beginning of all knowledge and all power,4 This he tells you to

believe, as a thing which he himself knows.

He will tell you nothing

but what he does know.

(2). Therefore, though

Giovanni Pisano and his fellow sculptors had given, literally,

the taking of the rib out of Adam's side, Giotto merely gives

the mythic expression of the truth he knows,—"they two shall

be one flesh."

(3). And though all the

theologians and poets of his time would have expected, if not

demanded, that his next assertion, after that of the Creation

of Man, should be of the Fall of Man, he asserts nothing of

the kind. He knows nothing of what man was. What he is, he

knows best of living men at that hour, and proceeds to say.

The next sculpture is of Eve spinning and Adam hewing the

ground into clods. Not digging: you cannot, usually,

dig but in ground already dug. The native earth you must hew.

They are not clothed in

skins. What would have been the use of Eve spinning if she

could not weave? They wear, each, one simple piece of drapery,

Adam's knotted behind him, Eve's fastened around her neck with

a rude brooch.

Above them are an oak

and an apple-tree. Into the apple-tree a little bear is trying

to climb.

The meaning of which

entire myth is, as I read it, that men and women must both eat

their bread with toil. That the first duty of man is to feed

his family, and the first duty of the woman to clothe it. That

the trees of the field are given us for strength and for

delight, and that the wild beasts of the field must have their

share with us.5

125. (4). The fourth

sculpture, forming the centre-piece of the series on the west

side, is nomad pastoral life.

Jabal, the father of

such as dwell in tents, and of such as have cattle, lifts the

curtain of his tent to look out upon his flock. His dog

watches it.

(5). Jubal, the father

of all such as handle the harp and organ.

That is to say, stringed

and wind instruments;—the lyre and reed. The first arts (with

the Jew and Greek) of the shepherd David, and shepherd Apollo.

Giotto has given him the

long level trumpet, afterwards adopted so grandly in the

sculptures of La Robbia and Donatello. It is, I think,

intended to be of wood, as now the long Swiss horn, and a long

and shorter tube are bound together.

(6). Tubal Cain, the

instructor of every artificer in brass and iron.

Giotto represents him as

sitting, fully robed, turning a wedge of bronze on the

anvil with extreme watchfulness.

These last three

sculptures, observe, represent the life of the race of Cain;

of those who are wanderers, and have no home. Nomad

pastoral life; Nomad artistic life, Wandering Willie; yonder

organ man, whom you want to send the policeman after, and the

gipsy who is mending the old schoolmistress's kettle on the

grass, which the squire has wanted so long to take into his

park from the roadside.

(7). Then the last

sculpture of the seven begins the story of the race of Seth,

and of home life. The father of it lying drunk under his

trellised vine; such the general image of civilized society,

in the abstract, thinks Giotto.

With several other

meanings, universally known to the Catholic world of that

day,—too many to be spoken of here.

126. The second side of

the tower represents, after this introduction, the sciences

and arts of civilized or home life.

(8). Astronomy. In nomad

life you may serve yourself of the guidance of the stars; but

to know the laws of their nomadic life, your own must

be fixed.

The astronomer, with his

sextant revolving on a fixed pivot, looks up to the vault of

the heavens and beholds their zodiac; prescient of what else

with optic glass the Tuscan artist viewed, at evening, from

the top of Fésole.

Above the dome of

heaven, as yet unseen, are the Lord of the worlds and His

angels. To-day, the Dawn and the Daystar: to-morrow, the

Daystar arising in the heart.

(9). Defensive

architecture. The building of the watchtower. The beginning of

security in possession.

(10). Pottery. The

making of pot, cup, and platter. The first civilized

furniture; the means of heating liquid, and serving drink and

meat with decency and economy.

(11). Riding. The

subduing of animals to domestic service.

(12). Weaving. The

making of clothes with swiftness, and in precision of

structure, by help of the loom.

(13). Law, revealed as

directly from heaven.

(14). Dædalus (not

Icarus, but the father trying the wings). The conquest of the

element of air.

127. As the seventh

subject of the first group introduced the arts of home after

those of the savage wanderer, this seventh of the second group

introduces the arts of the missionary, or civilized and

gift-bringing wanderer.

(15). The Conquest of

the Sea. The helmsman, and two rowers, rowing as Venetians,

face to bow.

(16). The Conquest of

the Earth. Hercules victor over Antæus. Beneficent strength of

civilization crushing the savageness of inhumanity.

(17). Agriculture. The

oxen and plough.

(18). Trade. The cart

and horses.

(19). And now the

sculpture over the door of the tower. The Lamb of God,

expresses the Law of Sacrifice, and door of ascent to heaven.

And then follow the fraternal arts of the Christian world.

(20). Geometry. Again

the angle sculpture, introductory to the following series. We

shall see presently why this science must be the foundation of

the rest.

(21). Sculpture.

(22). Painting.

(23). Grammar.

(24). Arithmetic. The

laws of number, weight, and measures of capacity.

(25) Music. The laws of

number, weight (or force), and measure, applied to sound.

(26). Logic. The laws of

number and measure applied to thought.

(27). The Invention of

Harmony.

128. You see now—by

taking first the great division of pre-Christian and Christian

arts, marked by the door of the Tower; and then the divisions

into four successive historical periods, marked by its

angles—that you have a perfect plan of human civilization. The

first side is of the nomad life, learning how to assert its

supremacy over other wandering creatures, herbs, and beasts.

Then the second side is the fixed home life, developing race

and country; then the third side, the human intercourse

between stranger races; then the fourth side, the harmonious

arts of all who are gathered into the fold of Christ.

129. Now let us return

to the first angle, and examine piece by piece with care.

(1). Creation of

Man.

Scarcely disengaged from

the clods of the earth, he opens his eyes to the face of

Christ. Like all the rest of the sculptures, it is less the

representation of a past fact than of a constant one. It is

the continual state of man, 'of the earth,' yet seeing God.

Christ holds the book of

His Law—the 'Law of life'—in His left hand.

The trees of the garden

above are,—central above Christ, palm (immortal life); above

Adam, oak (human life). Pear, and fig, and a large-leaved

ground fruit (what?) complete the myth of the Food of Life.

As decorative sculpture,

these trees are especially to be noticed, with those in the

two next subjects, and the Noah's vine as differing in

treatment from Giotto's foliage, of which perfect examples are

seen in 16 and 17. Giotto's branches are set in close

sheaf-like clusters; and every mass disposed with extreme

formality of radiation. The leaves of these first, on the

contrary, are arranged with careful concealment of their

ornamental system, so as to look inartificial. This is done so

studiously as to become, by excess, a little unnatural!—Nature

herself is more decorative and formal in grouping. But the

occult design is very noble, and every leaf modulated with

loving, dignified, exactly right and sufficient finish; not

done to show skill, nor with mean forgetfulness of main

subject, but in tender completion and harmony with it.

Look at the subdivisions

of the palm leaves with your magnifying glass. The others are

less finished in this than in the next subject. Man himself

incomplete, the leaves that are created with him, for his

life, must not be so.

(Are not his fingers yet

short; growing?)

130. (2). Creation

of Woman.

Far, in its essential

qualities, the transcendent sculpture of this subject,

Ghiberti's is only a dainty elaboration and beautification of

it, losing its solemnity and simplicity in a flutter of

feminine grace. The older sculptor thinks of the Uses of

Womanhood, and of its dangers and sins, before he thinks of

its beauty; but, were the arm not lost, the quiet naturalness

of this head and breast of Eve, and the bending grace of the

submissive rendering of soul and body to perpetual guidance by

the hand of Christ—(grasping the arm, note, for full

support)—would be felt to be far beyond Ghiberti's in beauty,

as in mythic truth.

The line of her body

joins with that of the serpent-ivy round the tree trunk above

her: a double myth—of her fall, and her support afterwards by

her husband's strength. "Thy desire shall be to thy husband."

The fruit of the tree—double-set filbert, telling nevertheless

the happy equality.

The leaves in this piece

are finished with consummate poetical care and precision.

Above Adam, laurel (a virtuous woman is a crown to her

husband); the filbert for the two together; the fig, for

fruitful household joy (under thy vine and fig-tree6—but vine properly the

masculine joy); and the fruit taken by Christ for type of all

naturally growing food, in his own hunger.

Examine with lens the

ribbing of these leaves, and the insertion on their stem of

the three laurel leaves on extreme right: and observe that in

all cases the sculptor works the moulding with his own

part of the design; look how he breaks variously deeper into

it, beginning from the foot of Christ, and going up to the

left into full depth above the shoulder.

131. (3). Original

labour.

Much poorer, and

intentionally so. For the myth of the creation of humanity,

the sculptor uses his best strength, and shows supremely the

grace of womanhood; but in representing the first peasant

state of life, makes the grace of woman by no means her

conspicuous quality. She even walks awkwardly; some feebleness

in foreshortening the foot also embarrassing the sculptor. He

knows its form perfectly—but its perspective, not quite yet.

The trees stiff and

stunted—they also needing culture. Their fruit dropping at

present only into beasts' mouths.

132. (4). Jabal.

If you have looked long

enough, and carefully enough, at the three previous

sculptures, you cannot but feel that the hand here is utterly

changed. The drapery sweeps in broader, softer, but less true

folds; the handling is far more delicate; exquisitely

sensitive to gradation over broad surfaces—scarcely using an

incision of any depth but in outline; studiously reserved in

appliance of shadow, as a thing precious and local—look at it

above the puppy's head, and under the tent. This is assuredly

painter's work, not mere sculptor's. I have no doubt whatever

it is by the own hand of the shepherd-boy of Fésole. Cimabue

had found him drawing, (more probably scratching with

Etrurian point,) one of his sheep upon a stone. These, on the

central foundation-stone of his tower he engraves, looking

back on the fields of life: the time soon near for him to draw

the curtains of his tent.

I know no dog like this

in method of drawing, and in skill of giving the living form

without one touch of chisel for hair, or incision for eye,

except the dog barking at Poverty in the great fresco of

Assisi.

Take the lens and look

at every piece of the work from corner to corner—note

especially as a thing which would only have been enjoyed by a

painter, and which all great painters do intensely enjoy—the fringe

of the tent,7 and precise insertion of its point in the

angle of the hexagon, prepared for by the archaic masonry

indicated in the oblique joint above;8 architect and painter

thinking at once, and doing as they thought.

I gave a lecture to the

Eton boys a year or two ago, on little more than the

shepherd's dog, which is yet more wonderful in magnified scale

of photograph. The lecture is partly published—somewhere, but

I can't refer to it.

133. (5). Jubal.

Still Giotto's, though a

little less delighted in; but with exquisite introduction of

the Gothic of his own tower. See the light surface sculpture

of a mosaic design in the horizontal moulding.

Note also the painter's

freehand working of the complex mouldings of the table—also

resolvedly oblong, not square; see central flower.

(6). Tubal Cain.

Still Giotto's, and

entirely exquisite; finished with no less care than the

shepherd, to mark the vitality of this art to humanity; the

spade and hoe—its heraldic bearing—hung on the hinged door.9 For subtlety of

execution, note the texture of wooden block under anvil, and

of its iron hoop.

The workman's face is

the best sermon on the dignity of labour yet spoken by

thoughtful man. Liberal Parliaments and fraternal Reformers

have nothing essential to say more.

(7). Noah.

Andrea Pisano's again,

more or less imitative of Giotto's work.

134. (8). Astronomy.

We have a new hand here

altogether. The hair and drapery bad; the face expressive, but

blunt in cutting; the small upper heads, necessarily little

more than blocked out, on the small scale; but not suggestive

of grace in completion: the minor detail worked with great

mechanical precision, but little feeling; the lion's head,

with leaves in its ears, is quite ugly; and by comparing the

work of the small cusped arch at the bottom with Giotto's soft

handling of the mouldings of his, in 5, you may for ever know

common mason's work from fine Gothic. The zodiacal signs are

quite hard and common in the method of bas-relief, but quaint

enough in design: Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces, on the

broad heavenly belt; Taurus upside down, Gemini, and Cancer,

on the small globe.

I think the whole a

restoration of the original panel, or else an inferior

workman's rendering of Giotto's design, which the next piece

is, with less question.

(9). Building.

The larger figure, I am

disposed finally to think, represents civic power, as in

Lorenzetti's fresco at Siena. The extreme rudeness of the

minor figures may be guarantee of their originality; it is the

smoothness of mass and hard edge work that make me suspect the

8th for a restoration.

(10). Pottery.

Very grand; with much

painter's feeling, and fine mouldings again. The tiled

roof projecting in the shadow above, protects the first

Ceramicus-home. I think the women are meant to be carrying

some kind of wicker or reed-bound water-vessel. The Potter's

servant explains to them the extreme advantages of the new

invention. I can't make any conjecture about the author of

this piece.

(11). Riding.

Again Andrea Pisano's,

it seems to me. Compare the tossing up of the dress behind the

shoulders, in 3 and 2. The head is grand, having nearly an

Athenian profile: the loss of the horse's fore-leg prevents me

from rightly judging of the entire action. I must leave riders

to say.

135. (12). Weaving.

Andrea's again, and of

extreme loveliness; the stooping face of the woman at the loom

is more like a Leonardo drawing than sculpture. The action of

throwing the large shuttle, and all the structure of the loom

and its threads, distinguishing rude or smooth surface, are

quite wonderful. The figure on the right shows the use and

grace of finely woven tissue, under and upper—that over the

bosom so delicate that the line of separation from the flesh

of the neck is unseen.

If you hide with your

hand the carved masonry at the bottom, the composition

separates itself into two pieces, one disagreeably

rectangular. The still more severely rectangular masonry

throws out by contrast all that is curved and rounded in the

loom, and unites the whole composition; that is its aesthetic

function; its historical one is to show that weaving is

queen's work, not peasant's; for this is palace masonry.

(13). The Giving of

Law.

More strictly, of the

Book of God's Law: the only one which can ultimately

be obeyed.10

The authorship of this

is very embarrassing to me. The face of the central figure is

most noble, and all the work good, but not delicate; it is

like original work of the master whose design No. 8 might be a

restoration.

(14). Dædalus.

Andrea Pisano again; the

head superb, founded on Greek models, feathers of wings

wrought with extreme care; but with no precision of

arrangement or feeling. How far intentional in awkwardness, I

cannot say; but note the good mechanism of the whole plan,

with strong standing board for the feet.

136. (15). Navigation.

An intensely puzzling

one; coarse (perhaps unfinished) in work, and done by a man

who could not row; the plaited bands used for rowlocks being

pulled the wrong way. Right, had the rowers been rowing

Englishwise: but the water at the boat's head shows its motion

forwards, the way the oarsmen look. I cannot make out the

action of the figure at the stern; it ought to be steering

with the stern oar.

The water seems quite

unfinished. Meant, I suppose, for surface and section of sea,

with slimy rock at the bottom; but all stupid and inefficient.

(16). Hercules and

Antæus.

The Earth power, half

hidden by the earth, its hair and hand becoming roots, the

strength of its life passing through the ground into the oak

tree. With Cercyon, but first named, (Plato, Laws,

book VII., 796), Antæus is the master of contest without use;—φιλονεικίας άχρήστου—and is generally the

power of pure selfishness and its various inflation to

insolence and degradation to cowardice;—finding its strength

only in fall back to its Earth,—he is the master, in a word,

of all such kind of persons as have been writing lately about

the "interests of England." He is, therefore, the Power

invoked by Dante to place Virgil and him in the lowest circle

of Hell;—"Alcides whilom felt,—that grapple, straitened sore,"

etc. The Antæus in the sculpture is very grand; but the

authorship puzzles me, as of the next piece, by the same hand.

I believe both Giotto's design.

137. (17). Ploughing.

The sword in its

Christian form. Magnificent: the grandest expression of the

power of man over the earth and its strongest creatures that I

remember in early sculpture,—(or for that matter, in late). It

is the subduing of the bull which the sculptor thinks most of;

the plough, though large, is of wood, and the handle slight.

But the pawing and bellowing labourer he has bound to it!—here

is victory.

(18). The Chariot.

The horse also subdued

to draught—Achilles' chariot in its first, and to be its last,

simplicity. The face has probably been grand—the figure is so

still. Andrea's, I think by the flying drapery.

(19). The Lamb, with

the symbol of Resurrection.

Over the door: 'I am the

door;—by me, if any man enter in,' etc. Put to the right of

the tower, you see, fearlessly, for the convenience of

staircase ascent; all external symmetry being subject with the

great builders to interior use; and then, out of the rightly

ordained infraction of formal law, comes perfect beauty; and

when, as here, the Spirit of Heaven is working with the

designer, his thoughts are suggested in truer order, by the

concession to use. After this sculpture comes the Christian

arts,—those which necessarily imply the conviction of

immortality. Astronomy without Christianity only reaches as

far as—'Thou hast made him a little lower than the angels—and

put all things under His feet':—Christianity says

beyond this,—'Know ye not that we shall judge angels (as also

the lower creatures shall judge us!)'11 The series of

sculptures now beginning, show the arts which can only

be accomplished through belief in Christ.

138. (20). Geometry.

Not 'mathematics': they

have been implied long ago in astronomy and architecture; but

the due Measuring of the Earth and all that is on it. Actually

done only by Christian faith—first inspiration of the great

Earth-measurers. Your Prince Henry of Spain, your Columbus,

your Captain Cook, (whose tomb, with the bright artistic

invention and religious tenderness which are so peculiarly the

gifts of the nineteenth century, we have just provided a fence

for, of old cannon open-mouthed, straight up towards

Heaven—your modern method of symbolizing the only appeal to

Heaven of which the nineteenth century has left itself

capable—'The voice of thy Brother's blood crieth to me'—your

outworn cannon, now silently agape, but sonorous in the ears

of angels with that appeal)—first inspiration, I say, of

these; constant inspiration of all who set true landmarks and

hold to them, knowing their measure; the devil interfering, I

observe, lately in his own way, with the Geometry of

Yorkshire, where the landed proprietors,12 when the neglected

walls by the roadside tumble down, benevolently repair the

same, with better stonework, outside always of the

fallen heaps;—which, the wall being thus built on what

was the public road, absorb themselves, with help of moss and

time, into the heaving swells of the rocky field-and behold,

gain of a couple of feet—along so much of the road as needs

repairing operations.

This then, is the first

of the Christian sciences: division of land rightly, and the

general law of measuring between wisely-held compass points.

The type of mensuration, circle in square, on his desk, I use

for my first exercise in the laws of Fésole.

139. (21). Sculpture.

The first piece of the

closing series on the north side of the Campanile, of which

some general points must be first noted, before any special

examination.

The two initial ones,

Sculpture and Painting, are by tradition the only ones

attributed to Giotto's own hand. The fifth, Song, is known,

and recognizable in its magnificence, to be by Luca della

Robbia. The remaining four are all of Luca's school,—later

work therefore, all these five, than any we have been hitherto

examining, entirely different in manner, and with late

flower-work beneath them instead of our hitherto severe Gothic

arches. And it becomes of course instantly a vital

question—Did Giotto die leaving the series incomplete, only

its subjects chosen, and are these two bas-reliefs of

Sculpture and Painting among his last works? or was the series

ever completed, and these later bas-reliefs substituted for

the earlier ones, under Luca's influence, by way of conducting

the whole to a grander close, and making their order more

representative of Florentine art in its fulness of power?

140. I must repeat, once

more, and with greater insistence respecting Sculpture than

Painting, that I do not in the least set myself up for a

critic of authenticity,—but only of absolute goodness. My

readers may trust me to tell them what is well done or ill;

but by whom, is quite a separate question, needing for any

certainty, in this school of much-associated masters and

pupils, extremest attention to minute particulars not at all

bearing on my objects in teaching.

Of this closing group of

sculptures, then, all I can tell you is that the fifth is a

quite magnificent piece of work, and recognizably, to my

extreme conviction, Luca della Robbia's; that the last,

Harmonia, is also fine work; that those attributed to Giotto

are fine in a different way,—and the other three in reality

the poorest pieces in the series, though done with much more

advanced sculptural dexterity.

But I am chiefly puzzled

by the two attributed to Giotto, because they are much coarser

than those which seem to me so plainly his on the west side,

and slightly different in workmanship—with much that is common

to both, however, in the casting of drapery and mode of

introduction of details. The difference may be accounted for

partly by haste or failing power, partly by the artist's less

deep feeling of the importance of these merely symbolic

figures, as compared with those of the Fathers of the Arts;

but it is very notable and embarrassing notwithstanding,

complicated as it is with extreme resemblance in other

particulars.

141. You cannot compare

the subjects on the tower itself; but of my series of

photographs take 6 and 21, and put them side by side.

I need not dwell on the

conditions of resemblance, which are instantly visible; but

the difference in the treatment of the heads is

incomprehensible. That of the Tubal Cain is exquisitely

finished, and with a painter's touch; every lock of the hair

laid with studied flow, as in the most beautiful drawing. In

the 'Sculpture,' it is struck out with ordinary tricks of

rapid sculptor trade, entirely unfinished, and with

offensively frank use of the drill hole to give picturesque

rustication to the beard.

Next, put 22 and 5 back

to back. You see again the resemblance in the earnestness of

both figures, in the unbroken arcs of their backs, in the

breaking of the octagon moulding by the pointed angles; and

here, even also in the general conception of the heads. But

again, in the one of Painting, the hair is struck with more

vulgar indenting and drilling, and the Gothic of the picture

frame is less precise in touch and later in style. Observe,

however,—and this may perhaps give us some definite hint for

clearing the question,—a picture-frame would be less

precise in making, and later in style, properly, than cusped

arches to be put under the feet of the inventor of all musical

sound by breath of man. And if you will now compare finally

the eager tilting of the workman's seat in 22 and 6, and the

working of the wood in the painter's low table for his pots of

colour, and his three-legged stool, with that of Tubal Cain's

anvil block; and the way in which the lines of the forge and

upper triptych are in each composition used to set off the

rounding of the head, I believe you will have little

hesitation in accepting my own view of the matter—namely, that

the three pieces of the Fathers of the Arts were wrought with

Giotto's extremest care for the most precious stones of his

tower; that also, being a sculptor and painter, he did the

other two, but with quite definite and wilful resolve that

they should be, as mere symbols of his own two trades,

wholly inferior to the other subjects of the patriarchs; that

he made the Sculpture picturesque and bold as you see it is,

and showed all a sculptor's tricks in the work of it; and a

sculptor's Greek subject, Bacchus, for the model of it; that

he wrought the Painting, as the higher art, with more care,

still keeping it subordinate to the primal subjects, but

showed, for a lesson to all the generations of painters for

evermore,—this one lesson, like his circle of pure line

containing all others,—'Your soul and body must be all in

every touch.'

143. I can't resist the

expression of a little piece of personal exultation, in

noticing that he holds his pencil as I do myself: no writing

master, and no effort (at one time very steady for many

months), having ever cured me of that way of holding both pen

and pencil between my fore and second finger; the third and

fourth resting the backs of them on my paper.

144. As I finally

arrange these notes for press, I am further confirmed in my

opinion by discovering little finishings in the two later

pieces which I was not before aware of. I beg the masters of

High Art, and sublime generalization, to take a good

magnifying glass to the 'Sculpture' and look at the way Giotto

has cut the compasses, the edges of the chisels, and the

keyhole of the lock of the toolbox. For the rest, nothing

could be more probable, in the confused and perpetually false

mass of Florentine tradition, than the preservation of the

memory of Giotto's carving his own two trades, and the

forgetfulness, or quite as likely ignorance, of the part he

took with Andrea Pisano in the initial sculptures.

145. I now take up the

series of subjects at the point where we broke off, to trace

their chain of philosophy to its close. To Geometry, which

gives to every man his possession of house and land, succeed

21, Sculpture, and 22, Painting, the adornments of permanent

habitation. And then, the great arts of education in a

Christian home. First—

(23). Grammar,

or more properly Literature altogether, of which we have

already seen the ancient power in the Spanish Chapel series;

then,

(24). Arithmetic,

central here as also in the Spanish Chapel, for the same

reasons; here, more impatiently asserting, with both hands,

that two, on the right, you observe-and two on the left-do

indeed and for ever make Four. Keep your accounts, you, with

your book of double entry, on that principle; and you will be

safe in this world and the next, in your steward's office. But

by no means so, if you ever admit the usurers Gospel of

Arithmetic, that two and two make Five.

You see by the rich hem

of his robe that the asserter of this economical first

principle is a man well to do in the world.

(25). Song.

The essential power of

music in animal life. Orpheus. the symbol of it all, the

inventor properly of Music, the Law of Kindness, as Dædalus of

Music, the Law of Construction. Hence the "Orphic life" is one

of ideal mercy, (vegetarian,)—Plato, Laws, Book VI.,

782,—and he is named first after Dædalus, and in balance to

him as head of the school of harmonists, in Book III., 677,

(Steph.) Look for the two singing birds clapping their wings

in the tree above him; then the five mystic beasts,—closest to

his feet the irredeemable boar; then lion and bear, tiger,

unicorn, and fiery dragon closest to his head, the flames of

its mouth mingling with his breath as he sings. The audient

eagle, alas! has lost the beak, and is only recognizable by

his proud holding of himself; the duck, sleepily delighted

after muddy dinner, close to his shoulder, is a true conquest.

Hoopoe, or indefinite bird of crested race, behind; of the

other three no clear certainty. The leafage throughout such as

only Luca could do, and the whole consummate in skill and

understanding.

(26).

Logic.

The art of Demonstration. Vulgarest of the whole series; far too

expressive of the mode in which argument is conducted by those

who are not masters of its reins.

(27). Harmony.

Music of Song, in the

full power of it, meaning perfect education in all art of the

Muses and of civilized life: the mystery of its concord is

taken for the symbol of that of a perfect state; one day,

doubtless, of the perfect world. So prophesies the last corner

stone of the Shepherd's Tower.

Notes

1· · He

wrote thus to me on 11th November last: "The three preachers

are certainly different. The first is Dominic; the second,

Peter Martyr, whom I have identified from his martyrdom on the

other wall; and the third, Aquinas."

2· · See

Fors Clavigera in that year.

· · For

account

of the series on the main archivolt of St. Mark's, see my

sketch of the schools of Venetian sculpture in third

forthcoming number of 'St. Mark's Rest.'

3· · So

also the Master-builder of the Ducal Palace of Venice. See

Fors Clavigera for June of this year.

· · The

oak and apple boughs are placed, with the same meaning, by

Sandro Botticelli, in the lap of Zipporah. The figure of the

bear is again represented by Jacopo della Quercia, on the

north door of the Cathedral of Florence. I am not sure of its

complete meaning.

4· · Compare

Fors

Clavigera, February, 1877.

5· · "I

think

Jabal's tent is made of leather; the relaxed intervals between

the tent-pegs show a curved ragged edge like leather near the

ground" (Mr. Caird). The edge of the opening is still more

characteristic, I think.

6· · Prints

of

these photographs which do not show the masonry all round the

hexagon are quite valueless for study.

7· · Pointed

out

to me by Mr. Caird, who adds farther, "I saw a forge identical

with this one at Pelago the other day,—the anvil resting on a

tree-stump: the same fire, bellows, and implements; the door

in two parts, the upper part like a shutter, and used for the

exposition of finished work as a sign of the craft; and I saw

upon it the same finished work of the same shape as in the

bas-relief—a spade and a hoe."

8· · Mr.

Caird

convinced me of the real meaning of this sculpture. I had

taken it for the giving of a book, writing further of it as

follows:— All books, rightly so called, are Books of Law, and

all Scripture is given by inspiration of God. (What we

now mostly call a book, the infinite reduplication and

vibratory echo of a lie, is not given but belched up out of

volcanic clay by the inspiration of the devil.) On the

Book-giver's right hand the students in cell, restrained by

the lifted right hand: "Silent, you, till you know"; then,

perhaps, you also. On the left, the men of the world,

kneeling, receive the gift. Recommendable seal, this, for Mr.

Mudie! Mr. Caird says: "The book is written law, which is

given by Justice to the inferiors, that they may know the laws

regulating their relations to their superiors—who are also

under the hand of law. The vassal is protected by the

accessibility of formularized law. The superior is restrained

by the right hand of power."

9· · In

the deep sense of this truth, which underlies all the bright

fantasy and humour of Mr. Courthope's "Paradise of Birds,"

that rhyme of the risen spirit of Aristophanes may well be

read under the tower of Giotto, beside his watch-dog of the

fold.

10· I mean no accusation

against any class; probably the one-fielded statesman is more

eager for his little gain of fifty yards of grass than the

squire for his bite and sup out of the gypsy's part of the

roadside. But it is notable enough to the passing traveller,

to find himself shut into a narrow road between high stone

dykes which he can neither see over nor climb over, (I always

deliberately pitch them down myself, wherever I need a gap,)

instead of on a broad road between low grey walls with all the

moor beyond—and the power of leaping over when he chooses in

innocent trespass for herb, or view, or splinter of grey rock.

FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII,

VIII,

IX,

X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA