FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2022: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII

, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New: Opere

Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

ROBERT BROWNING'S

'ANDREA DEL SARTO'

AS DOUBLE SELF-PORTRAIT

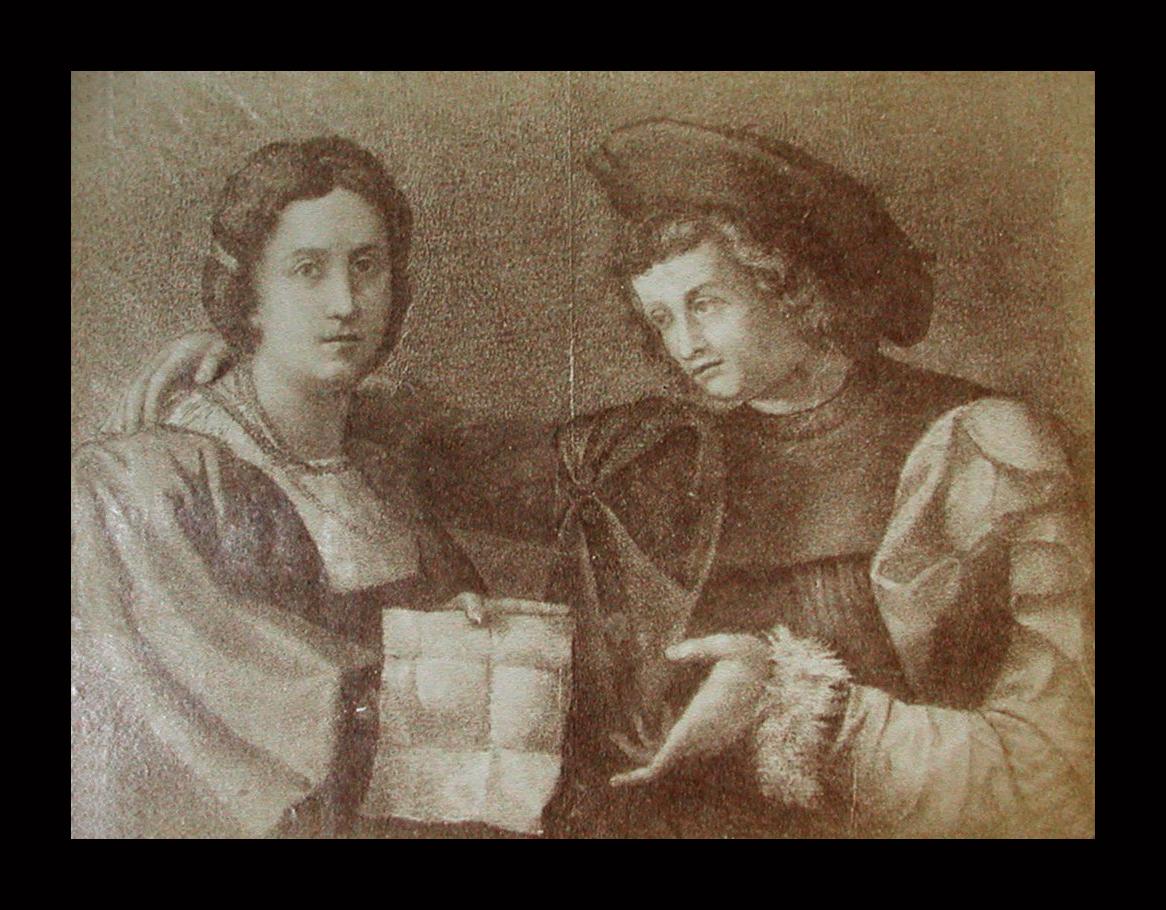

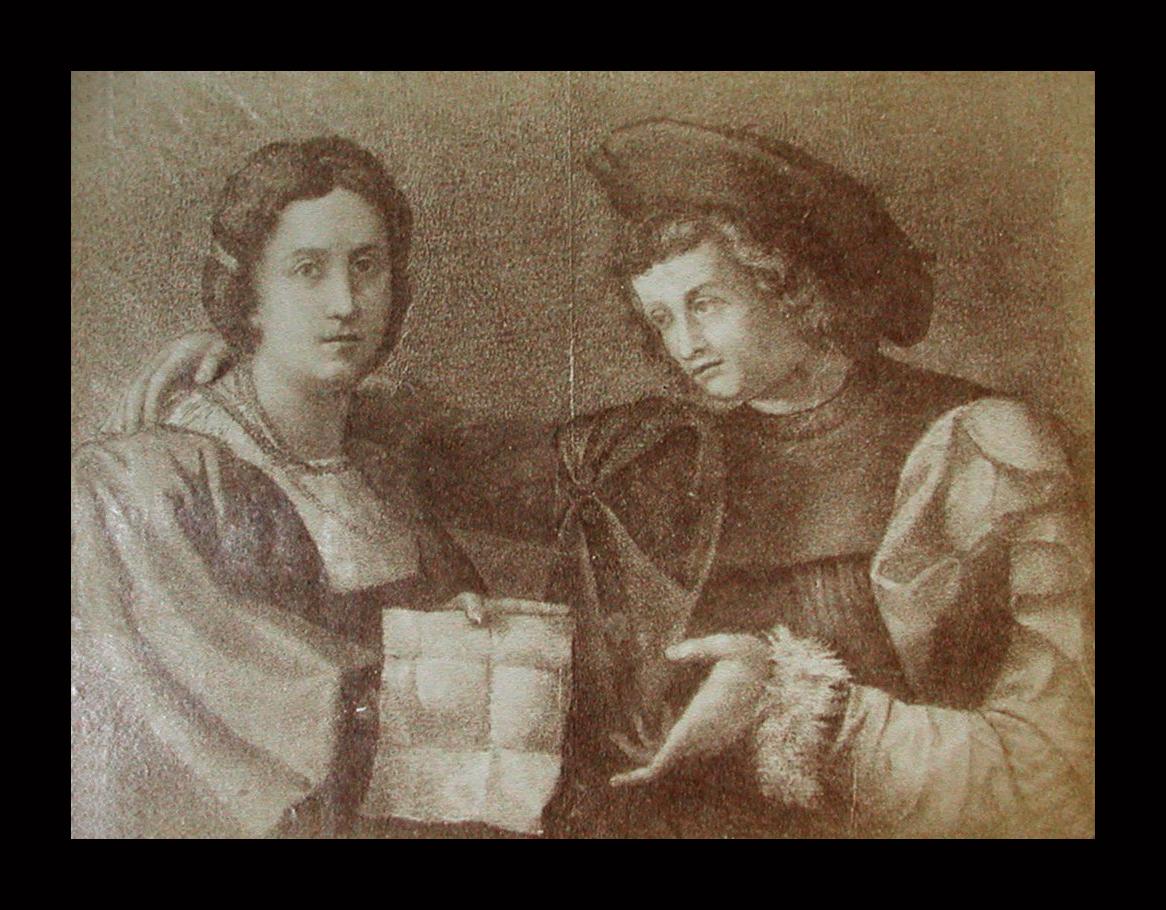

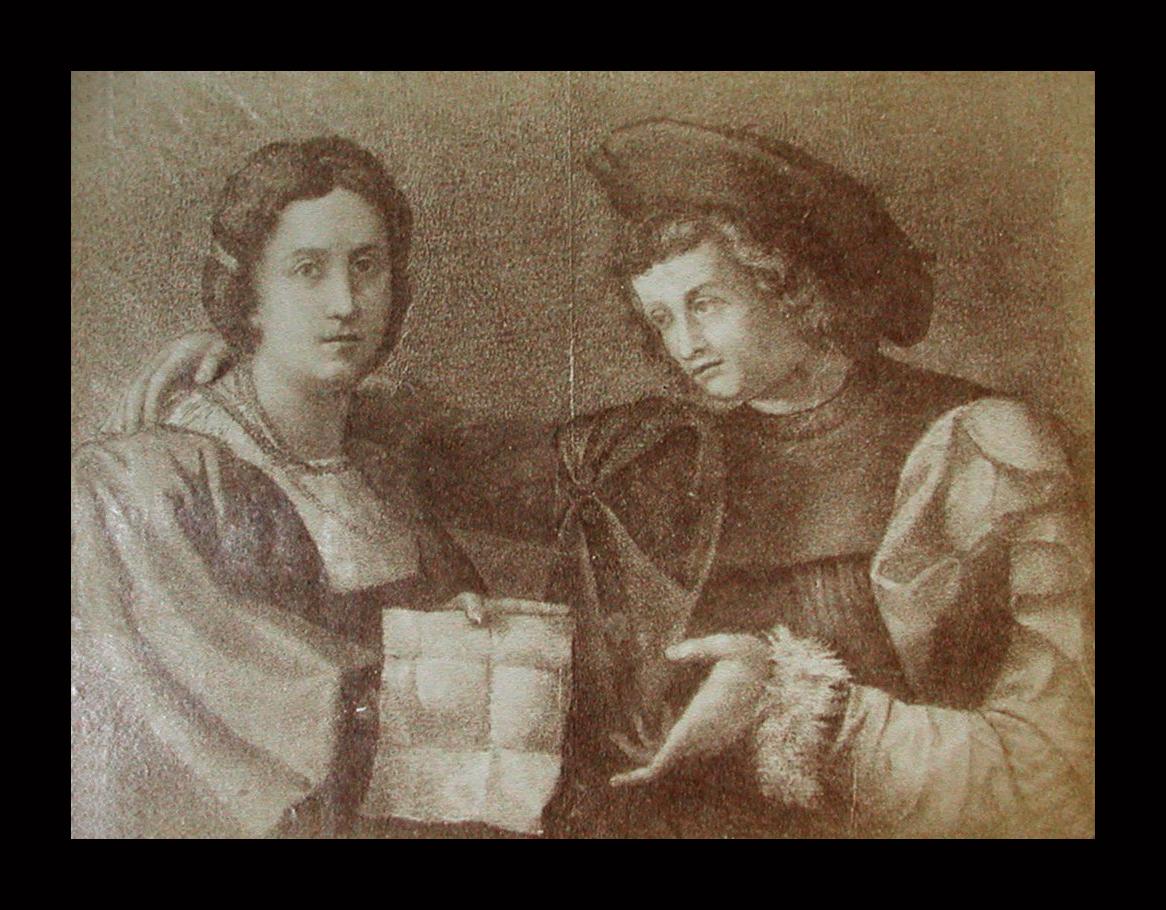

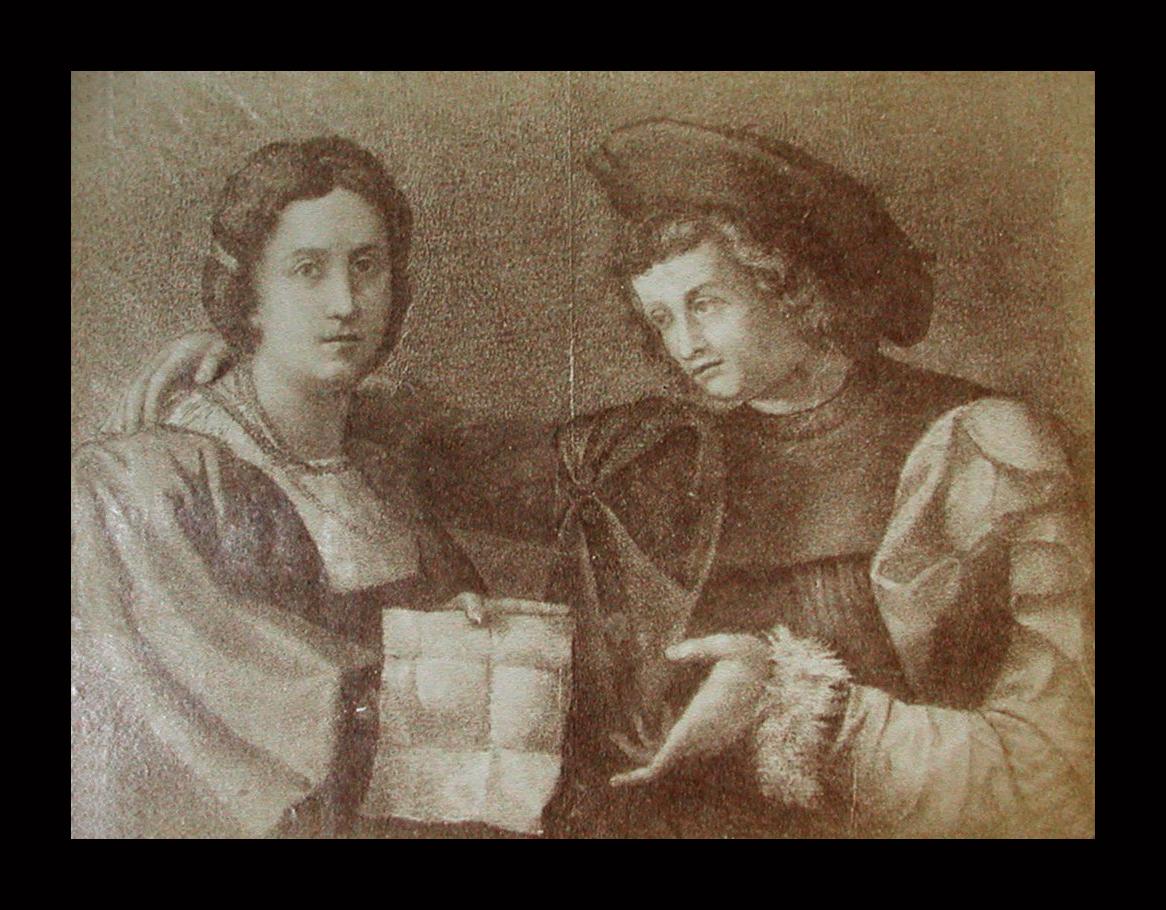

N. 15934. Galleria Pitti. Ritratto di Andrea del

Sarto e di Lucrezia del Fede sua moglie. Andrea del Sarto.

For larger image, click here

Edward

Dowden in his fine but now forgotten book, The Life of Robert

Browning (London. Dent, 1915/1927),

in a footnote on page 191, states that

Mrs Andrew Crosse, in her

article, 'John Kenyon and his Friends' (Temple Bar Magazine,

April 1900), writes: 'When the Brownings were living in

Florence, Kenyon had begged them to procure for him a

copy of the portrait in the Pitti of Andea del Sarto and

his wife. Mr Browning was unable to get the copy made

with any promise of satisfaction, and so wrote the

exquisite poem of Andrea del Sarto - and sent it to

Kenyon!'

Here is the poem

in its original English (in Italian one can find it published at

http://www.marsilioeditori.it/libri/scheda-libro/3176884/andrea-del-sarto):

But do not let us quarrel any more,

No, my

Lucrezia; bear with me for once:

Sit down

and all shall happen as you wish.

You turn

your face, but does it bring your heart?

I'll work

then for your friend's friend, never fear,

Treat his

own subject after his own way,

Fix his

own time, accept too his own price,

And shut

the money into this small hand

When next

it takes mine. Will it? tenderly?

Oh, I'll

content him, - but to-morrow, Love!

I often

am much wearier than you think,

This

evening more than usual, and it seems

As if -

forgive now - should you let me sit

Here by

the window with your hand in mine

And look

a half-hour forth on Fiesole,

Both of

one mind, as married people use,

Quietly,

quietly the evening through,

I might

get up to-morrow to my work

Cheerful

and fresh as ever. Let us try.

To-morrow,

how you shall be glad for this!

Your soft

hand is a woman of itself,

And mine

the man's bared breast she curls inside.

Don't

count the time lost, neither; you must serve

For each

of the five pictures we require:

It saves

a model. So! keep looking so -

My

serpentining beauty, rounds on rounds!

How could

you ever prick those perfect ears,

Even to

put the pearl there! oh, so sweet -

My face,

my moon, my everybody's moon,

Which

everybody looks on and calls his,

And, I

suppose, is looked on by in turn,

While she

looks - no one's: very dear, no less.

You

smile? why, there's my picture ready made,

There's

what we painters call our harmony!

A common

greyness silvers everything, -

All in a

twilight, you and I alike

- You, at

the point of your first pride in me

(That's

gone you know), - but I, at every point;

My youth,

my hope, my art, being all toned down

To yonder

sober pleasant Fiesole.

There's

the bell clinking from the chapel-top;

That

length of convent-wall across the way

Holds the

trees safer, huddled more inside;

The last

monk leaves the garden; days decrease,

And

autumn grows, autumn in everything.

Eh? the

whole seems to fall into a shape

As if I

saw alike my work and self

And all

that I was born to be and do,

A

twilight-piece. Love, we are in God's hand.

How

strange now, looks the life he makes us lead;

So free

we seem, so fettered fast we are!

I feel he

laid the fetter: let it lie!

This

chamber for example - turn your head -

All

that's behind us! You don't understand

Nor care

to understand about my art,

But you

can hear at least when people speak:

And that

cartoon, the second from the door

- It is

the thing, Love! so such things should be -

Behold

Madonna! - I am bold to say.

I can do

with my pencil what I know,

What I

see, what at bottom of my heart

I wish

for, if I ever wish so deep -

Do

easily, too - when I say, perfectly,

I do not

boast, perhaps: yourself are judge,

Who

listened to the Legate's talk last week,

And just

as much they used to say in France.

At any

rate 'tis easy, all of it!

No

sketches first, no studies, that's long past:

I do what

many dream of, all their lives,

- Dream?

strive to do, and agonize to do,

And fail

in doing. I could count twenty such

On twice

your fingers, and not leave this town,

Who

strive - you don't know how the others strive

To paint

a little thing like that you smeared

Carelessly

passing with your robes afloat, -

Yet do

much less, so much less, Someone says,

(I know

his name, no matter) - so much less!

Well,

less is more, Lucrezia: I am judged.

There

burns a truer light of God in them,

In their

vexed beating stuffed and stopped-up brain,

Heart, or

whate'er else, than goes on to prompt

This

low-pulsed forthright craftsman's hand of mine.

Their

works drop groundward, but themselves, I know,

Reach

many a time a heaven that's shut to me,

Enter and

take their place there sure enough,

Though

they come back and cannot tell the world.

My works

are nearer heaven, but I sit here.

The

sudden blood of these men! at a word -

Praise

them, it boils, or blame them, it boils too.

I,

painting from myself and to myself,

Know what

I do, am unmoved by men's blame

Or their

praise either. Somebody remarks

Morello's

outline there is wrongly traced,

His hue

mistaken; what of that? or else,

Rightly

traced and well ordered; what of that?

Speak as

they please, what does the mountain care?

Ah, but a

man's reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what's

a heaven for? All is silver-grey,

Placid

and perfect with my art: the worse!

I know

both what I want and what might gain,

And yet

how profitless to know, to sigh

"Had I

been two, another and myself,

"Our head

would have o'erlooked the world!" No doubt.

Yonder's

a work now, of that famous youth

The

Urbinate who died five years ago.

('Tis

copied, George Vasari sent it me.)

Well, I

can fancy how he did it all,

Pouring

his soul, with kings and popes to see,

Reaching,

that heaven might so replenish him,

Above and

through his art - for it gives way;

That arm

is wrongly put - and there again -

A fault

to pardon in the drawing's lines,

Its body,

so to speak: its soul is right,

He means

right - that, a child may understand.

Still,

what an arm! and I could alter it:

But all

the play, the insight and the stretch -

(Out of

me, out of me! And wherefore out?

Had you

enjoined them on me, given me soul,

We might

have risen to Rafael, I and you!

Nay,

Love, you did give all I asked, I think -

More than

I merit, yes, by many times.

But had

you - oh, with the same perfect brow,

And

perfect eyes, and more than perfect mouth,

And the

low voice my soul hears, as a bird

The

fowler's pipe, and follows to the snare -

Had you,

with these the same, but brought a mind!

Some

women do so. Had the mouth there urged

"God and

the glory! never care for gain.

"The

present by the future, what is that?

"Live for

fame, side by side with Agnolo!

"Rafael

is waiting: up to God, all three!"

I might

have done it for you. So it seems:

Perhaps

not. All is as God over-rules.

Beside,

incentives come from the soul's self;

The rest

avail not. Why do I need you?

What wife

had Rafael, or has Agnolo?

In this

world, who can do a thing, will not;

And who

would do it, cannot, I perceive:

Yet the

will's somewhat - somewhat, too, the power -

And thus

we half-men struggle. At the end,

God, I

conclude, compensates, punishes.

'Tis

safer for me, if the award be strict,

That I am

something underrated here,

Poor this

long while, despised, to speak the truth.

I dared

not, do you know, leave home all day,

For fear

of chancing on the Paris lords.

The best

is when they pass and look aside;

But they

speak sometimes; I must bear it all.

Well may

they speak! That Francis, that first time,

And that

long festal year at Fontainebleau!

I surely

then could sometimes leave the ground,

Put on

the glory, Rafael's daily wear,

In that

humane great monarch's golden look, -

One

finger in his beard or twisted curl

Over his

mouth's good mark that made the smile,

One arm

about my shoulder, round my neck,

The

jingle of his gold chain in my ear,

I

painting proudly with his breath on me,

All his

court round him, seeing with his eyes,

Such

frank French eyes, and such a fire of souls

Profuse,

my hand kept plying by those hearts, -

And, best

of all, this, this, this face beyond,

This in

the background, waiting on my work,

To crown

the issue with a last reward!

A good

time, was it not, my kingly days?

And had

you not grown restless... but I know -

'Tis done

and past: 'twas right, my instinct said:

Too live

the life grew, golden and not grey,

And I'm

the weak-eyed bat no sun should tempt

Out of

the grange whose four walls make his world.

How could

it end in any other way?

You

called me, and I came home to your heart.

The

triumph was - to reach and stay there; since

I reached

it ere the triumph, what is lost?

Let my

hands frame your face in your hair's gold,

You

beautiful Lucrezia that are mine!

"Rafael

did this, Andrea painted that;

"The

Roman's is the better when you pray,

"But

still the other's Virgin was his wife - "

Men will

excuse me. I am glad to judge

Both

pictures in your presence; clearer grows

My better

fortune, I resolve to think.

For, do

you know, Lucrezia, as God lives,

Said one

day Agnolo, his very self,

To Rafael

. . . I have known it all these years . . .

(When the

young man was flaming out his thoughts

Upon a

palace-wall for Rome to see,

Too

lifted up in heart because of it)

"Friend,

there's a certain sorry little scrub

"Goes up

and down our Florence, none cares how,

"Who,

were he set to plan and execute

"As you

are, pricked on by your popes and kings,

"Would

bring the sweat into that brow of yours!"

To

Rafael's! - And indeed the arm is wrong.

I hardly

dare . . . yet, only you to see,

Give the

chalk here - quick, thus, the line should go!

Ay, but

the soul! he's Rafael! rub it out!

Still,

all I care for, if he spoke the truth,

(What he?

why, who but Michel Agnolo?

Do you

forget already words like those?)

If really

there was such a chance, so lost, -

Is,

whether you're - not grateful - but more pleased.

Well, let

me think so. And you smile indeed!

This hour

has been an hour! Another smile?

If you

would sit thus by me every night

I should

work better, do you comprehend?

I mean

that I should earn more, give you more.

See, it

is settled dusk now; there's a star;

Morello's

gone, the watch-lights show the wall,

The

cue-owls speak the name we call them by.

Come from

the window, love, - come in, at last,

Inside

the melancholy little house

We built

to be so gay with. God is just.

King

Francis may forgive me: oft at nights

When I

look up from painting, eyes tired out,

The walls

become illumined, brick from brick

Distinct,

instead of mortar, fierce bright gold,

That gold

of his I did cement them with!

Let us

but love each other. Must you go?

That

Cousin here again? he waits outside?

Must see

you - you, and not with me? Those loans?

More

gaming debts to pay? you smiled for that?

Well, let

smiles buy me! have you more to spend?

While

hand and eye and something of a heart

Are left

me, work's my ware, and what's it worth?

I'll pay

my fancy. Only let me sit

The grey

remainder of the evening out,

Idle, you

call it, and muse perfectly

How I

could paint, were I but back in France,

One

picture, just one more - the Virgin's face,

Not yours

this time! I want you at my side

To hear

them - that is, Michel Agnolo -

Judge all

I do and tell you of its worth.

Will you?

To-morrow, satisfy your friend.

I take

the subjects for his corridor,

Finish

the portrait out of hand - there, there,

And throw

him in another thing or two

If he

demurs; the whole should prove enough

To pay

for this same Cousin's freak. Beside,

What's

better and what's all I care about,

Get you

the thirteen scudi for the ruff!

Love,

does that please you? Ah, but what does he,

The

Cousin! what does he to please you more?

I am

grown peaceful as old age to-night.

I regret

little, I would change still less.

Since

there my past life lies, why alter it?

The very

wrong to Francis! - it is true

I took

his coin, was tempted and complied,

And built

this house and sinned, and all is said.

My father

and my mother died of want.

Well, had

I riches of my own? you see

How one

gets rich! Let each one bear his lot.

They were

born poor, lived poor, and poor they died:

And I

have laboured somewhat in my time

And not

been paid profusely. Some good son

Paint my

two hundred pictures - let him try!

No doubt,

there's something strikes a balance. Yes,

You loved

me quite enough, it seems to-night.

This must

suffice me here. What would one have?

In

heaven, perhaps, new chances, one more chance -

Four

great walls in the New Jerusalem,

Meted on

each side by the angel's reed,

For

Leonard, Rafael, Agnolo and me

To cover

- the three first without a wife,

While I

have mine! So - still they overcome

Because

there's still Lucrezia, - as I choose.

Again the

Cousin's whistle! Go, my Love.

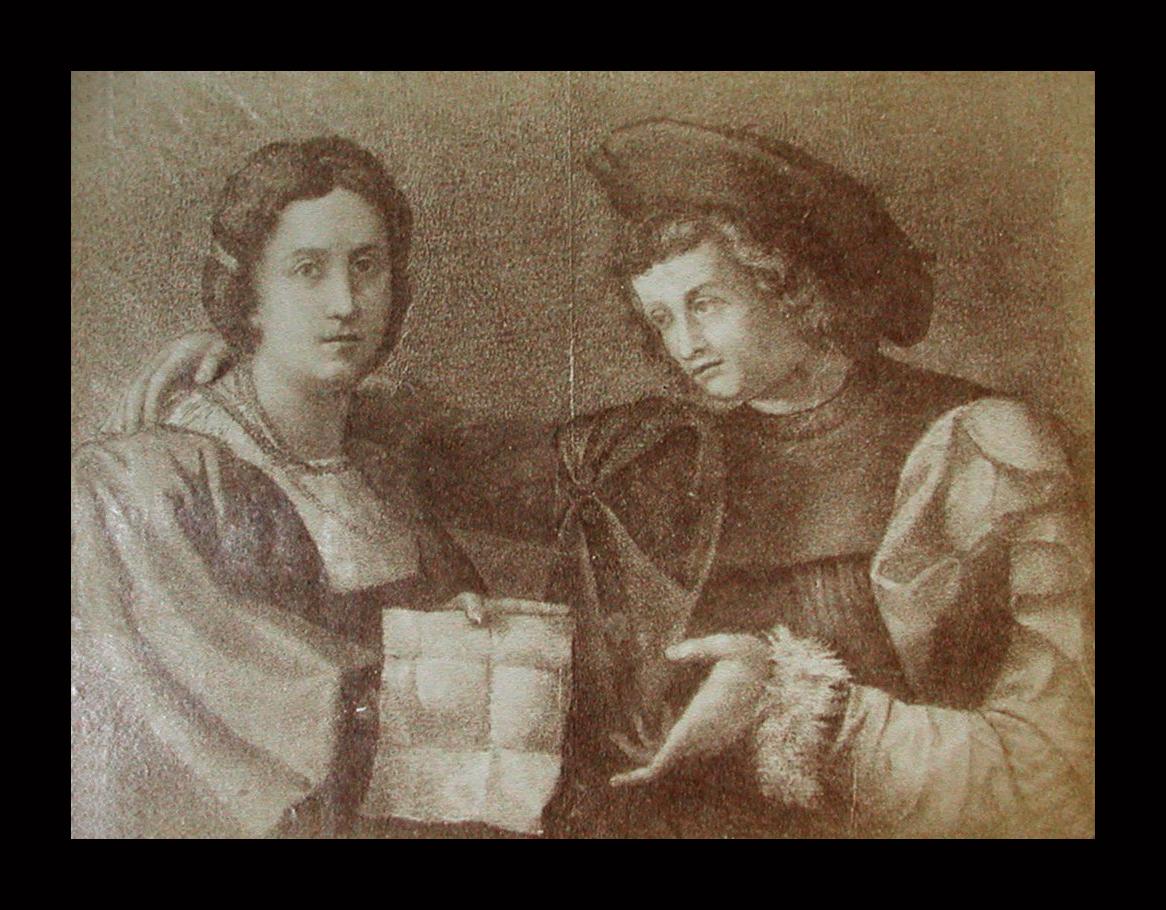

N. 15934. Galleria Pitti. Ritratto di Andrea del

Sarto e di Lucrezia del Fede sua moglie. Andrea del Sarto.

For larger image, click here

These two paintings, now much obscured by darkening varnish, are

hung separately in the Pitti Gallery in Florence, and are no

longer attributed to Andrea del Sarto, but were very much

admired in the Victorian period, who were such avid readers of

Vasari's account of this and other artists' lives. Photographers

joined them up together. In an ancient album of engravings of

the Palace Collection, the following truncated account is given

of the painting.

Andrea Del Sarto

Due ritratti, ambidue

di sua mano

Ecco le sembianze, che di sè col penello effigava il

celebre Andrea del Sarto, nel

quale uno mostrarono la natura e l'arte tutto quello che può

far la pittura mediante il disegno, il colorire e

l'invenzione, diceva del suo maestro, Giorgio Vasari,

che ognuno sa quanta avesse nelle artistiche discipline e

sagacia d'occhio e dirittura manifesto nel presente ritratto,

che basterebbe a provarlo stupendo lavoro della sua mano: ma a

farcene più certi soccorre il rilievo della figura, che dalla

tela distaccasi, in guisa da reputarla faccia d'uom vivo e

parlante: illusione mirabile e cara, che nei dipinti di quel

famoso deriva dalla magìa d'invisibili mezze-tinte; privilegio

suo tutto, che lo solleva al primato dell'arte, e il fa dagli

emuli singolare: di sorta che basta essere mezzanamente

versati nelle cose della pittura, per ravvisare a colpo

d'occhio, anche fra mille, un su quadro. Paonazza è la vesta,

e piacquesi tratteggiarla quasi con sprezzo, o, come suol

dirsi, alla presta;

non senza però che tanto vi sieno pronunciate le pieghe,

quanto è richiesto a farla ondeggiare con verità e con

naturalezza. Difficile economia che i sommi artisti

caratterizza, e separa dai mediocri: i quali credendo far

pompa d'ingegno e di fantasia sbracciansi a raffazzonare le

oopere loro con un subisso di mendicati ornamenti.

Maggiormente spicca e si anima la carnagione del volto sotto

il nero berretto che impose al capo, e che lasciando già¹

dalla fronte, mezzo scoperta, scappar fuori dietro le orecchie

divisi in due list lunghissime folte e crespe i capegli,

gl'impronta nella fisonomia la mansuetudine e la shiettezza

del cuore. Nè a questa sua effigie conento, la ricopiava per

assicurarsi forse ch'una almeno durasse ai posteri, testimonio

di ciò che era nella fattezze, e nel tempo stess di ciò che

poteva nell'arte: e tuttedue le possiede e conserva la patria

sua nella Gallaeria Palatina e nella Galleria delle Statue.

Passiamo ora e considerarlo nell'altro quadro ov'egli di nuovo

di rappresenta le sue sembianze, e quelle della sua donna.

'Non ti sia grave, o Lucrezia, di leggere codesto foglio e

vedrai come parla a nome di un re: il quale mi è stato, e da

capo vuol essermi liberale di beneficj. Per far pago il

desiderio tuo, guarda se tu mi sei caramente diletta, ne

abbandonai la splendid corte, dove d'ogni sorta ricevetti

amorevoli cortesie e segnalati compensi, e dove se avessi

fermata la mira dimora, sarei, non v'ha dubbio, salito,

lasciam star le ricchezze, a onoratissimo grado. Ma nel

congedarmi da lui, che, soprammodo incresioso a vedermi

partire studiava rimovermi con gentili violenze dal mio

proposto, di tornarvi in tua compagnia, dopo alcni mesi

trascorsi, obbligai con giuramento la fede. Il mettere più

tempo in mezzo me tornerebbe a grave discapito e a grave

torto. Osserva di grazia come degna exxitarmi con amichevoli

richiami, e con generosa modestia a mantener la promessa? Or

dì: come scioglermi di tanto debito? come tradire tante

speranze? a sè turpe e a sè mostruosa ingratitudine quale, non

dico perdono, ma scusa? come d'infamia sarà notato il

mio nome! Risolviti adunque da quella che sei donna savia e

prudente; vieni con essomeco e provvedi in uno al nostro

decoro e al nostro interesse: viene a Parigi: colà si onorano

con lodi e con guiderdoni le opere . . .

But we lack the other page or the engraving, these large folios

coming from an Antiquarian going into retirement who gave us

engravings he had not yet sold.

Giorgio Vasari, Andrea del Sarto's pupil, wrote his life

among many others, and gives much information concerning his

marriage to the widow Lucrezia del Fede. Interestingly, his

account differs in significant ways from Robert Browning's

re-telling. Vasari's life begins with an account of his

training, of his coming to the Santissima Annunziata of the

Servites, and of his paintings for them. Then it adds:

These works brought Andrea into greater notice, and

many pictures and works of importance were entrusted to him,

and he made for himself so great a name in the city that he

was considered one of the first painters, and although he had

asked little for his works he found himself in a position to

help his relatives. But falling in love with a young woman who

was left a widow, he took her for his wife, and had enough to

do all the rest of his life, and had to work harder than he

had ever done before, for besides the duties and liabilities

which belong to such a union, he took upon him many more

troubles, being constantly vexed with jealousy and one thing

and another. And all who knew his case felt compassion for

him, and blamed the simplicity which had reduced him to such a

condition. He had been much sought after by his friends

before, but now he was avoided. For though his pupils stayed

with him, hoping to learn something from him, there was not

one, great or small, who did not suffer by her evil words or

blows during the time he was there.

Nevertheless,

this torment seemed to him the highest pleasure. He never put

a woman in any picture which he did not draw from her, for

even if another sat to him, through seeing her constantly and

having drawn her so often, and, what is more, having her

impressed on his mind, it always came about that the head

resembled hers.

A certain

Florentine, Giovanni Battista Puccini, being extraordinarily

pleased with Andrea's work, charged him to paint a picture of

our Lady to send to France, but it was so beautiful that he

kept it himself and did not send it away. However, trafficking

constantly with France, and being employed to send good

pictures there, he gave Andrea another picture to paint, a

dead Christ supported by angels. When it was done every one

was so pleased with it that Andrea was entreated to let it be

engraved in Rome by Agostino Veniziano, but as it did not

succeed very well he would never let any other of his pictures

be engraved. The picture itself gave no less pleasure to

France than it had done in Italy, and the king gave orders

that Andrea should do another, in consequence of which he

resolved at his friend's persuasion to go himself to France.

But that year 1515 the Florentines, hearing that Pope Leo X

meant to honour his native place with a visit, gave orders

that he should be received with great feasting, and such

magnificent decorations were prepared, with arches, statues,

and other ornaments, as had never been seen before, there

being at that time in the city a greater number of men of

genius and talent than there had ever been before. And what

was most admired was the façade of S. Maria del Fiore, made of

wood and painted with pictures by Andrea del Sarto, the

architecture being by Jacopo Sansovino, with some bas-reliefs

and statues, and the Pope pronounced that it could not have

been more beautiful it it had been in marble.

Meanwhile King Francis I, greatly admiring his works, was told

that Andrea would easily be persuaded to remove to France and

enter into his service; and the thing pleased the king well.

So he gave command that money should be paid him for his

journey; and Andrea set out joyfully for France, taking with

him Andrea Sguarzella his pupil. And having arrived at the

court, he was received lovingly by the king, and before the

first day was over experienced the liberality of that

magnanimous king, receiving gifts of money and rich garments.

He soon began to work and won the esteem of the king and the

whole court, being caressed by all, so that it seemed to him

he had passed from a state of extreme unhappiness to the

greatest felicity. among his first works he painted from life

the Dauphin, then only a few months old, and therefore in

swaddling clothes, and when he brought it to the king he

received for it three hundred crowns of gold. And the king,

that he might stay with him willingly, ordered that great

provision should be made for him, and that he should want for

nothing. But one day, while he was working upon a St Jerome

for the king's mother, there came to him letters from Lucrezia

his wife, whom he had left in Florence, and she wrote that

when he was away, although his letters told her he was well,

she could not cease from worries and constant weeping, using

many sweet words apt to touch the heart of a man who loved her

only too well, so that the poor man was nearly beside himself

when he read that if he did not return soon her would find her

dead. So he prayed the king for leave to go to Florence and

put his affairs in order, and bring his wife to France,

promising to bring with him on his return pictures and

sculptures of price. The king, trusting him, gave him money

for this purpose, and Andrea swore on the gospels to return in

a few months. He arrived in Florence happily, and enjoyed

himself with his beautiful wife and friends. At last, the time

having come when he ought to return to the king, he found

himself in extremity, for he had spent on building and on his

pleasure his own money and the king's also. Nevertheless he

would have returned, but the tears and prayers of his wife

prevailed against his promise to the king. When he did not

return the king was so angered that for a long time he would

not look at a Florentine painter, and swore that if ever

Andrea fell into his hands, it should be to his hurt, without

regard to his talents.

Stopping on

my way cycling

home from Mass, I photographed these two pictures just

beyond and opposite the Santissima Annunziata

. . .

He returned to Florence. Here he was employed by Giacomo, a

Servite friar, who, when absolving a woman from a vow, had

commanded her to have the figure of our Lady painted over a

door in the Nunziata. Finding Andrea, he told him that he had

this money to spend, and although it was not much, it would be

well done of him to undertake it; and Andrea, being

soft-hearted, was prevailed upon by the father's persuasions,

and painted in fresco our Lady with the Child in her arms, and

St Joseph leaning on a sack. This picture needs none to praise

it, for all can see it to be a most rare work.

One day Andrea had been painting the intendent of the monks of

Vallombrosa, and when the work was done some of the colour was

left over, and Andrea, taking a tile, called Lucretia, his

wife, and said, 'Come here, for as this colour is left, I will

paint you, that it may be seen how well you are preserved for

your age, and yet how you have changed and how different you

are from your first portraits'. But the woman, having some

fancy or other, would not sit still, and Andrea, as if he

guessed that he was near his end, took a mirror and painted

himself instead so well that the portrait seems alive. This

portrait is still in possession of Lucrezia his wife.

ROBERT BROWNING'S

'ANDREA DEL SARTO'

AS DOUBLE

SELF-PORTRAIT

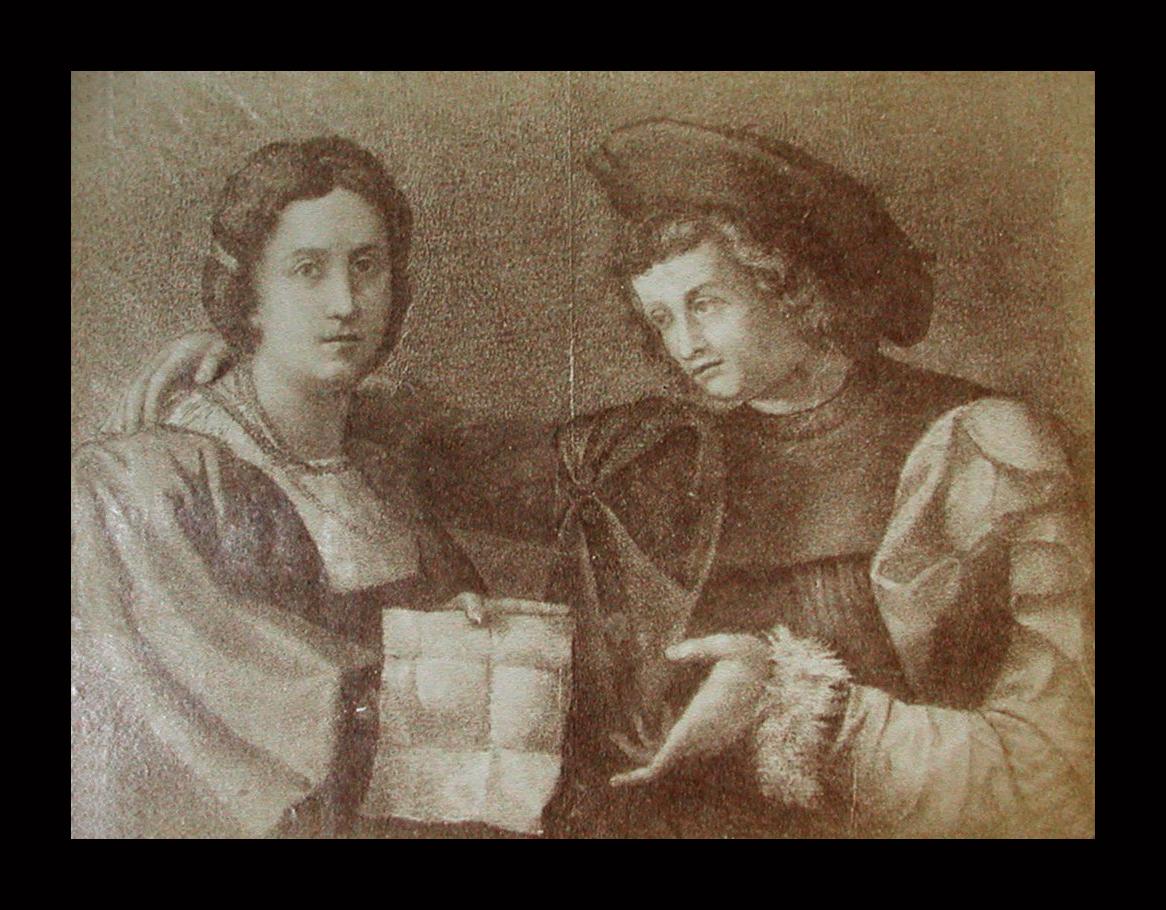

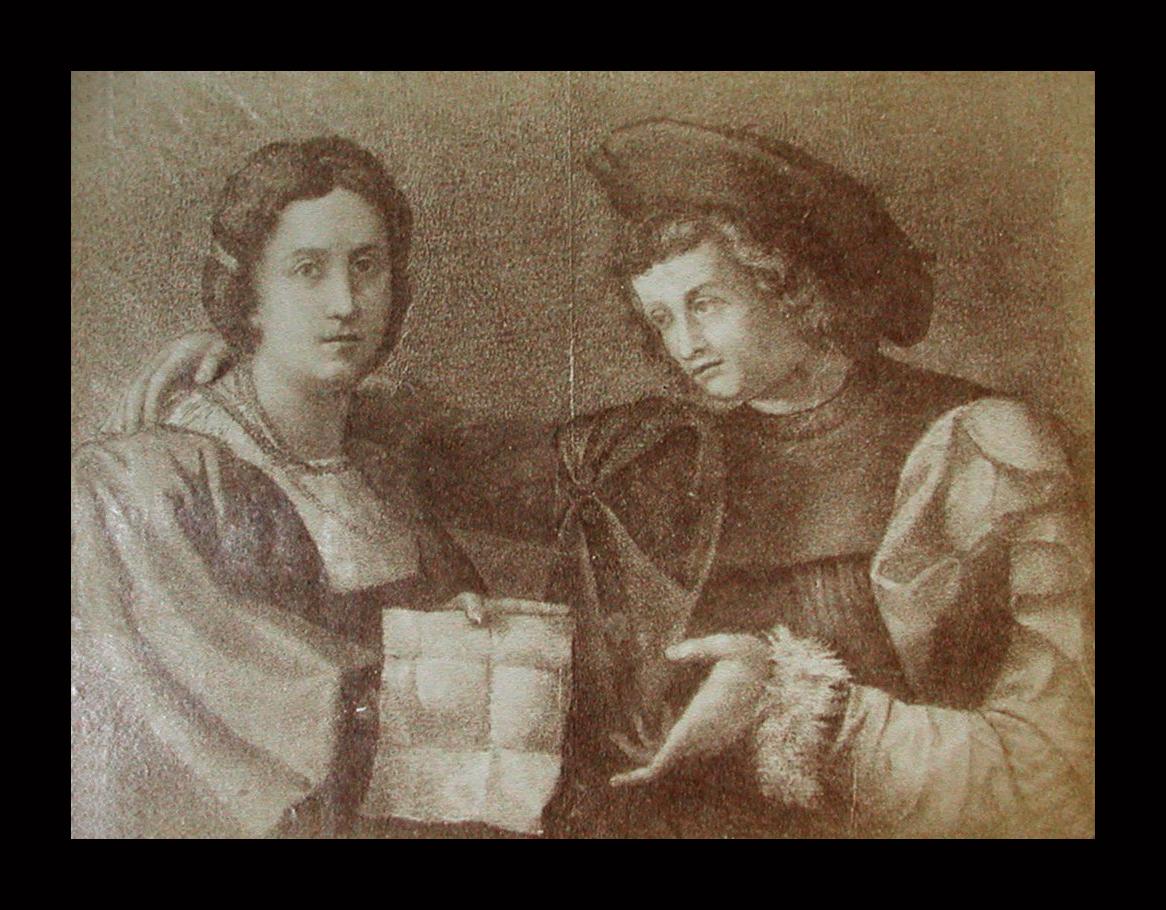

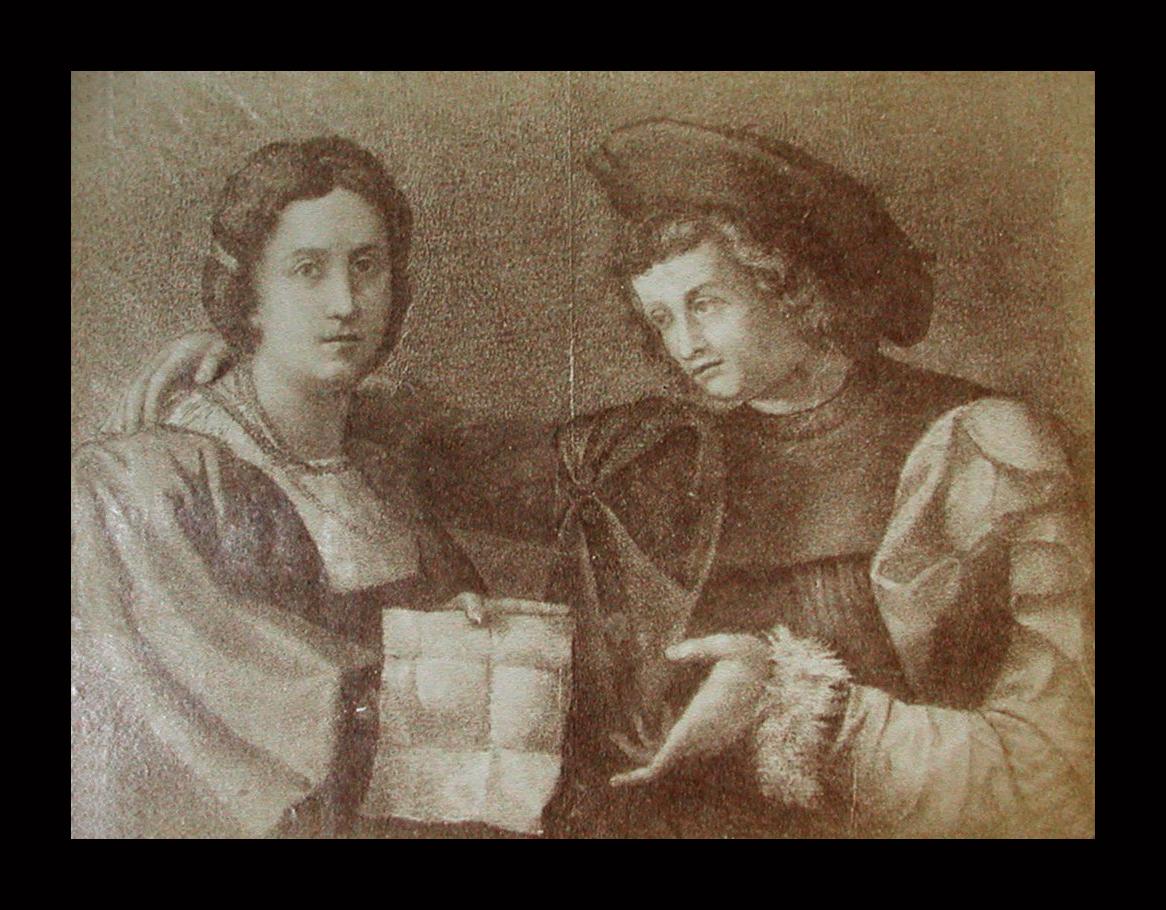

N. 15934. Galleria Pitti. Ritratto di Andrea del

Sarto e di Lucrezia del Fede sua moglie. Andrea del Sarto.

For larger image, click here

Edward

Dowden in his fine but now forgotten book, The Life of Robert

Browning (London. Dent, 1915/1927),

in a footnote on page 191, states that

Mrs Andrew

Crosse, in her article, 'John Kenyon and his Friends'

(Temple Bar Magazine,

April 1900), writes: 'When the Brownings were living

in Florence, Kenyon had begged them to procure for him

a copy of the portrait in the Pitti of Andea del Sarto

and his wife. Mr Browning was unable to get the copy

made with any promise of satisfaction, and so wrote

the exquisite poem of Andrea del Sarto - and sent it

to Kenyon!'

Here is the poem

in its original English (in Italian one can find it published

at

http://www.marsilioeditori.it/libri/scheda-libro/3176884/andrea-del-sarto):

But do not let us quarrel any more,

No, my

Lucrezia; bear with me for once:

Sit

down and all shall happen as you wish.

You

turn your face, but does it bring your heart?

I'll

work then for your friend's friend, never fear,

Treat

his own subject after his own way,

Fix his

own time, accept too his own price,

And

shut the money into this small hand

When

next it takes mine. Will it? tenderly?

Oh,

I'll content him, - but to-morrow, Love!

I often

am much wearier than you think,

This

evening more than usual, and it seems

As if -

forgive now - should you let me sit

Here by

the window with your hand in mine

And

look a half-hour forth on Fiesole,

Both of

one mind, as married people use,

Quietly,

quietly the evening through,

I might

get up to-morrow to my work

Cheerful

and fresh as ever. Let us try.

To-morrow,

how you shall be glad for this!

Your

soft hand is a woman of itself,

And

mine the man's bared breast she curls inside.

Don't

count the time lost, neither; you must serve

For

each of the five pictures we require:

It

saves a model. So! keep looking so -

My

serpentining beauty, rounds on rounds!

How

could you ever prick those perfect ears,

Even to

put the pearl there! oh, so sweet -

My

face, my moon, my everybody's moon,

Which

everybody looks on and calls his,

And, I

suppose, is looked on by in turn,

While

she looks - no one's: very dear, no less.

You

smile? why, there's my picture ready made,

There's

what we painters call our harmony!

A

common greyness silvers everything, -

All in

a twilight, you and I alike

- You,

at the point of your first pride in me

(That's

gone you know), - but I, at every point;

My

youth, my hope, my art, being all toned down

To

yonder sober pleasant Fiesole.

There's

the bell clinking from the chapel-top;

That

length of convent-wall across the way

Holds

the trees safer, huddled more inside;

The

last monk leaves the garden; days decrease,

And

autumn grows, autumn in everything.

Eh? the

whole seems to fall into a shape

As if I

saw alike my work and self

And all

that I was born to be and do,

A

twilight-piece. Love, we are in God's hand.

How

strange now, looks the life he makes us lead;

So free

we seem, so fettered fast we are!

I feel

he laid the fetter: let it lie!

This

chamber for example - turn your head -

All

that's behind us! You don't understand

Nor

care to understand about my art,

But you

can hear at least when people speak:

And

that cartoon, the second from the door

- It is

the thing, Love! so such things should be -

Behold

Madonna! - I am bold to say.

I can

do with my pencil what I know,

What I

see, what at bottom of my heart

I wish

for, if I ever wish so deep -

Do

easily, too - when I say, perfectly,

I do

not boast, perhaps: yourself are judge,

Who

listened to the Legate's talk last week,

And

just as much they used to say in France.

At any

rate 'tis easy, all of it!

No

sketches first, no studies, that's long past:

I do

what many dream of, all their lives,

-

Dream? strive to do, and agonize to do,

And

fail in doing. I could count twenty such

On

twice your fingers, and not leave this town,

Who

strive - you don't know how the others strive

To

paint a little thing like that you smeared

Carelessly

passing with your robes afloat, -

Yet do

much less, so much less, Someone says,

(I know

his name, no matter) - so much less!

Well,

less is more, Lucrezia: I am judged.

There

burns a truer light of God in them,

In

their vexed beating stuffed and stopped-up brain,

Heart,

or whate'er else, than goes on to prompt

This

low-pulsed forthright craftsman's hand of mine.

Their

works drop groundward, but themselves, I know,

Reach

many a time a heaven that's shut to me,

Enter

and take their place there sure enough,

Though

they come back and cannot tell the world.

My

works are nearer heaven, but I sit here.

The

sudden blood of these men! at a word -

Praise

them, it boils, or blame them, it boils too.

I,

painting from myself and to myself,

Know

what I do, am unmoved by men's blame

Or

their praise either. Somebody remarks

Morello's

outline there is wrongly traced,

His hue

mistaken; what of that? or else,

Rightly

traced and well ordered; what of that?

Speak

as they please, what does the mountain care?

Ah, but

a man's reach should exceed his grasp,

Or

what's a heaven for? All is silver-grey,

Placid

and perfect with my art: the worse!

I know

both what I want and what might gain,

And yet

how profitless to know, to sigh

"Had I

been two, another and myself,

"Our

head would have o'erlooked the world!" No doubt.

Yonder's

a work now, of that famous youth

The

Urbinate who died five years ago.

('Tis

copied, George Vasari sent it me.)

Well, I

can fancy how he did it all,

Pouring

his soul, with kings and popes to see,

Reaching,

that heaven might so replenish him,

Above

and through his art - for it gives way;

That

arm is wrongly put - and there again -

A fault

to pardon in the drawing's lines,

Its

body, so to speak: its soul is right,

He

means right - that, a child may understand.

Still,

what an arm! and I could alter it:

But all

the play, the insight and the stretch -

(Out of

me, out of me! And wherefore out?

Had you

enjoined them on me, given me soul,

We

might have risen to Rafael, I and you!

Nay,

Love, you did give all I asked, I think -

More

than I merit, yes, by many times.

But had

you - oh, with the same perfect brow,

And

perfect eyes, and more than perfect mouth,

And the

low voice my soul hears, as a bird

The

fowler's pipe, and follows to the snare -

Had

you, with these the same, but brought a mind!

Some

women do so. Had the mouth there urged

"God

and the glory! never care for gain.

"The

present by the future, what is that?

"Live

for fame, side by side with Agnolo!

"Rafael

is waiting: up to God, all three!"

I might

have done it for you. So it seems:

Perhaps

not. All is as God over-rules.

Beside,

incentives come from the soul's self;

The

rest avail not. Why do I need you?

What

wife had Rafael, or has Agnolo?

In this

world, who can do a thing, will not;

And who

would do it, cannot, I perceive:

Yet the

will's somewhat - somewhat, too, the power -

And

thus we half-men struggle. At the end,

God, I

conclude, compensates, punishes.

'Tis

safer for me, if the award be strict,

That I

am something underrated here,

Poor

this long while, despised, to speak the truth.

I dared

not, do you know, leave home all day,

For

fear of chancing on the Paris lords.

The

best is when they pass and look aside;

But

they speak sometimes; I must bear it all.

Well

may they speak! That Francis, that first time,

And

that long festal year at Fontainebleau!

I

surely then could sometimes leave the ground,

Put on

the glory, Rafael's daily wear,

In that

humane great monarch's golden look, -

One

finger in his beard or twisted curl

Over

his mouth's good mark that made the smile,

One arm

about my shoulder, round my neck,

The

jingle of his gold chain in my ear,

I

painting proudly with his breath on me,

All his

court round him, seeing with his eyes,

Such

frank French eyes, and such a fire of souls

Profuse,

my hand kept plying by those hearts, -

And,

best of all, this, this, this face beyond,

This in

the background, waiting on my work,

To

crown the issue with a last reward!

A good

time, was it not, my kingly days?

And had

you not grown restless... but I know -

'Tis

done and past: 'twas right, my instinct said:

Too

live the life grew, golden and not grey,

And I'm

the weak-eyed bat no sun should tempt

Out of

the grange whose four walls make his world.

How

could it end in any other way?

You

called me, and I came home to your heart.

The

triumph was - to reach and stay there; since

I

reached it ere the triumph, what is lost?

Let my

hands frame your face in your hair's gold,

You

beautiful Lucrezia that are mine!

"Rafael

did this, Andrea painted that;

"The

Roman's is the better when you pray,

"But

still the other's Virgin was his wife - "

Men

will excuse me. I am glad to judge

Both

pictures in your presence; clearer grows

My

better fortune, I resolve to think.

For, do

you know, Lucrezia, as God lives,

Said

one day Agnolo, his very self,

To

Rafael . . . I have known it all these years . . .

(When

the young man was flaming out his thoughts

Upon a

palace-wall for Rome to see,

Too

lifted up in heart because of it)

"Friend,

there's a certain sorry little scrub

"Goes

up and down our Florence, none cares how,

"Who,

were he set to plan and execute

"As you

are, pricked on by your popes and kings,

"Would

bring the sweat into that brow of yours!"

To

Rafael's! - And indeed the arm is wrong.

I

hardly dare . . . yet, only you to see,

Give

the chalk here - quick, thus, the line should go!

Ay, but

the soul! he's Rafael! rub it out!

Still,

all I care for, if he spoke the truth,

(What

he? why, who but Michel Agnolo?

Do you

forget already words like those?)

If

really there was such a chance, so lost, -

Is,

whether you're - not grateful - but more pleased.

Well,

let me think so. And you smile indeed!

This

hour has been an hour! Another smile?

If you

would sit thus by me every night

I

should work better, do you comprehend?

I mean

that I should earn more, give you more.

See, it

is settled dusk now; there's a star;

Morello's

gone, the watch-lights show the wall,

The

cue-owls speak the name we call them by.

Come

from the window, love, - come in, at last,

Inside

the melancholy little house

We

built to be so gay with. God is just.

King

Francis may forgive me: oft at nights

When I

look up from painting, eyes tired out,

The

walls become illumined, brick from brick

Distinct,

instead of mortar, fierce bright gold,

That

gold of his I did cement them with!

Let us

but love each other. Must you go?

That

Cousin here again? he waits outside?

Must

see you - you, and not with me? Those loans?

More

gaming debts to pay? you smiled for that?

Well,

let smiles buy me! have you more to spend?

While

hand and eye and something of a heart

Are

left me, work's my ware, and what's it worth?

I'll

pay my fancy. Only let me sit

The

grey remainder of the evening out,

Idle,

you call it, and muse perfectly

How I

could paint, were I but back in France,

One

picture, just one more - the Virgin's face,

Not

yours this time! I want you at my side

To hear

them - that is, Michel Agnolo -

Judge

all I do and tell you of its worth.

Will

you? To-morrow, satisfy your friend.

I take

the subjects for his corridor,

Finish

the portrait out of hand - there, there,

And

throw him in another thing or two

If he

demurs; the whole should prove enough

To pay

for this same Cousin's freak. Beside,

What's

better and what's all I care about,

Get you

the thirteen scudi for the ruff!

Love,

does that please you? Ah, but what does he,

The

Cousin! what does he to please you more?

I am

grown peaceful as old age to-night.

I

regret little, I would change still less.

Since

there my past life lies, why alter it?

The

very wrong to Francis! - it is true

I took

his coin, was tempted and complied,

And

built this house and sinned, and all is said.

My

father and my mother died of want.

Well,

had I riches of my own? you see

How one

gets rich! Let each one bear his lot.

They

were born poor, lived poor, and poor they died:

And I

have laboured somewhat in my time

And not

been paid profusely. Some good son

Paint

my two hundred pictures - let him try!

No

doubt, there's something strikes a balance. Yes,

You

loved me quite enough, it seems to-night.

This

must suffice me here. What would one have?

In

heaven, perhaps, new chances, one more chance -

Four

great walls in the New Jerusalem,

Meted

on each side by the angel's reed,

For

Leonard, Rafael, Agnolo and me

To

cover - the three first without a wife,

While I

have mine! So - still they overcome

Because

there's still Lucrezia, - as I choose.

Again

the Cousin's whistle! Go, my Love.

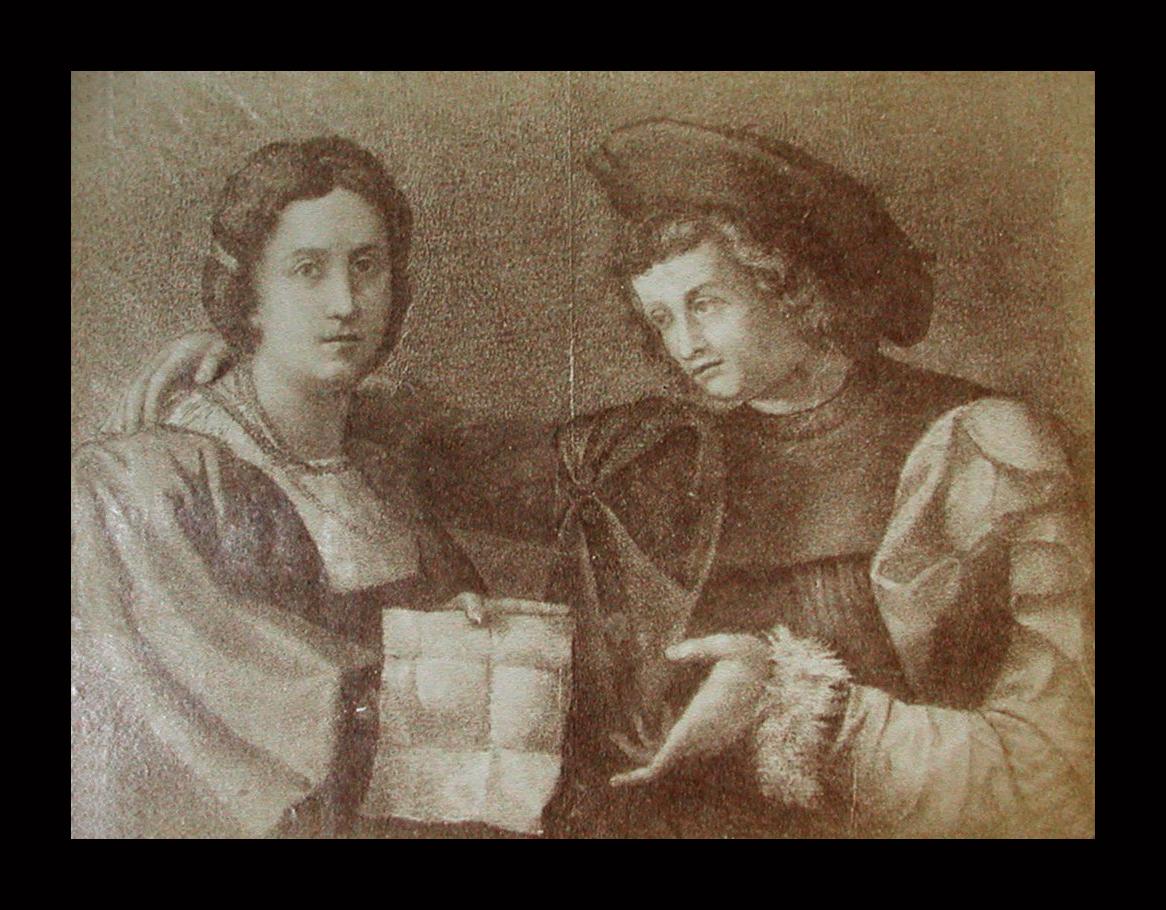

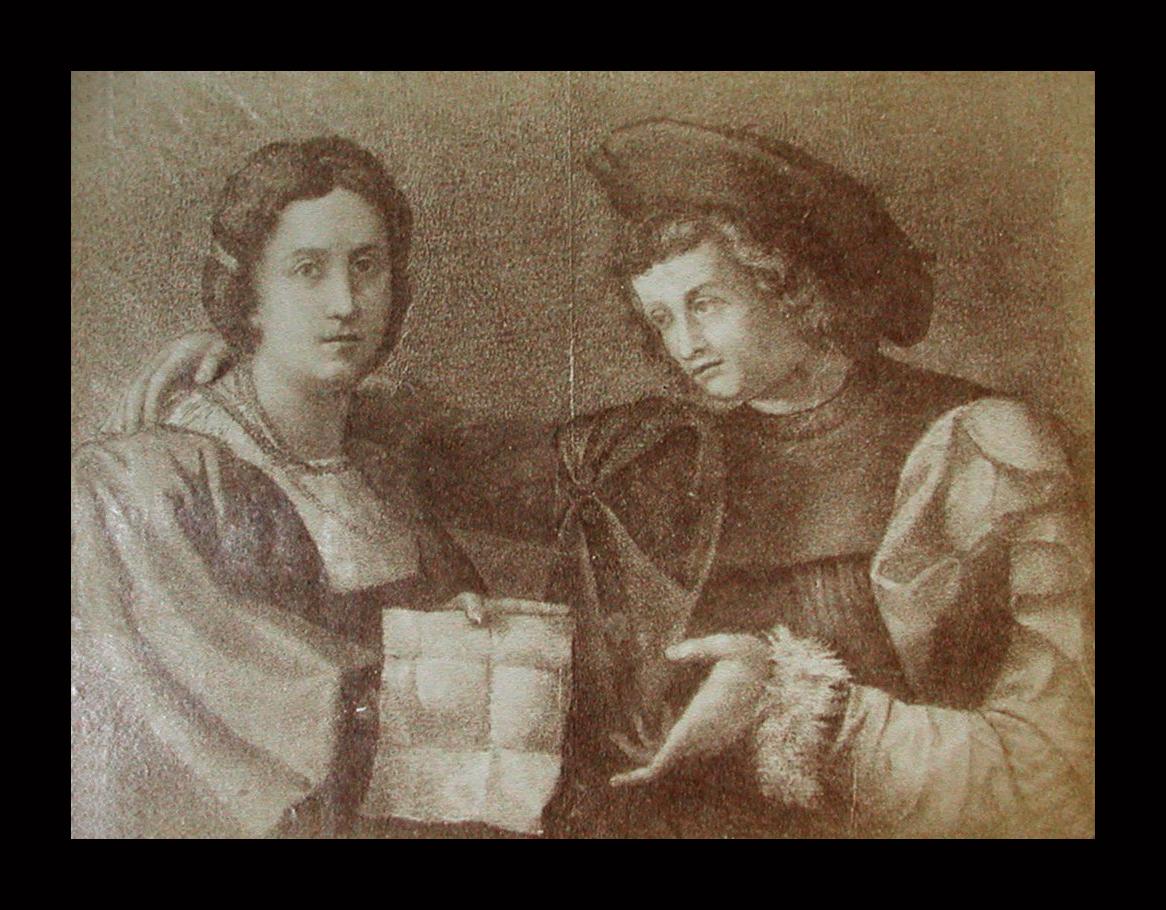

N. 15934. Galleria Pitti. Ritratto di Andrea del

Sarto e di Lucrezia del Fede sua moglie. Andrea del Sarto.

For larger image, click here

These two paintings, now much obscured by darkening varnish,

are hung separately in the Pitti Gallery in Florence, and are

no longer attributed to Andrea del Sarto, but were very much

admired in the Victorian period, who were such avid readers of

Vasari's account of this and other artists' lives.

Photographers joined them up together. In an ancient album of

engravings of the Palace Collection, the following truncated

account is given of the painting.

Andrea Del Sarto

Due ritratti,

ambidue di sua mano

Ecco le sembianze, che di sè col penello

effigava il celebre Andrea del Sarto, nel quale uno mostrarono la

natura e l'arte tutto quello che può far la pittura

mediante il disegno, il colorire e l'invenzione,

diceva del suo maestro, Giorgio Vasari, che ognuno sa quanta

avesse nelle artistiche discipline e sagacia d'occhio e

dirittura manifesto nel presente ritratto, che basterebbe a

provarlo stupendo lavoro della sua mano: ma a farcene più

certi soccorre il rilievo della figura, che dalla tela

distaccasi, in guisa da reputarla faccia d'uom vivo e

parlante: illusione mirabile e cara, che nei dipinti di quel

famoso deriva dalla magìa d'invisibili mezze-tinte;

privilegio suo tutto, che lo solleva al primato dell'arte, e

il fa dagli emuli singolare: di sorta che basta essere

mezzanamente versati nelle cose della pittura, per ravvisare

a colpo d'occhio, anche fra mille, un su quadro. Paonazza è

la vesta, e piacquesi tratteggiarla quasi con sprezzo, o,

come suol dirsi, alla

presta; non senza però che tanto vi sieno

pronunciate le pieghe, quanto è richiesto a farla ondeggiare

con verità e con naturalezza. Difficile economia che i

sommi artisti caratterizza, e separa dai mediocri: i quali

credendo far pompa d'ingegno e di fantasia sbracciansi a

raffazzonare le oopere loro con un subisso di mendicati

ornamenti. Maggiormente spicca e si anima la carnagione del

volto sotto il nero berretto che impose al capo, e che

lasciando gi๠dalla fronte, mezzo scoperta, scappar fuori

dietro le orecchie divisi in due list lunghissime folte e

crespe i capegli, gl'impronta nella fisonomia la

mansuetudine e la shiettezza del cuore. Nè a questa sua

effigie conento, la ricopiava per assicurarsi forse ch'una

almeno durasse ai posteri, testimonio di ciò che era nella

fattezze, e nel tempo stess di ciò che poteva nell'arte: e

tuttedue le possiede e conserva la patria sua nella

Gallaeria Palatina e nella Galleria delle Statue.

Passiamo ora e considerarlo nell'altro quadro ov'egli di

nuovo di rappresenta le sue sembianze, e quelle della sua

donna.

'Non ti sia grave, o Lucrezia, di leggere codesto foglio e

vedrai come parla a nome di un re: il quale mi è stato, e da

capo vuol essermi liberale di beneficj. Per far pago il

desiderio tuo, guarda se tu mi sei caramente diletta, ne

abbandonai la splendid corte, dove d'ogni sorta ricevetti

amorevoli cortesie e segnalati compensi, e dove se avessi

fermata la mira dimora, sarei, non v'ha dubbio, salito,

lasciam star le ricchezze, a onoratissimo grado. Ma nel

congedarmi da lui, che, soprammodo incresioso a vedermi

partire studiava rimovermi con gentili violenze dal mio

proposto, di tornarvi in tua compagnia, dopo alcni mesi

trascorsi, obbligai con giuramento la fede. Il mettere più

tempo in mezzo me tornerebbe a grave discapito e a grave

torto. Osserva di grazia come degna exxitarmi con amichevoli

richiami, e con generosa modestia a mantener la promessa? Or

dì: come scioglermi di tanto debito? come tradire tante

speranze? a sè turpe e a sè mostruosa ingratitudine quale,

non dico perdono, ma scusa? come d'infamia sarà notato

il mio nome! Risolviti adunque da quella che sei donna savia

e prudente; vieni con essomeco e provvedi in uno al nostro

decoro e al nostro interesse: viene a Parigi: colà si

onorano con lodi e con guiderdoni le opere . . .

But we lack the other page or the engraving, these large

folios coming from an Antiquarian going into retirement who

gave us engravings he had not yet sold.

Giorgio

Vasari, Andrea del Sarto's pupil, wrote his life among many

others, and gives much information concerning his marriage to

the widow Lucrezia del Fede. Interestingly, his account

differs in significant ways from Robert Browning's re-telling.

Vasari's life begins with an account of his training, of his

coming to the Santissima Annunziata of the Servites, and of

his paintings for them. Then it adds:

These works brought Andrea into greater

notice, and many pictures and works of importance were

entrusted to him, and he made for himself so great a name in

the city that he was considered one of the first painters,

and although he had asked little for his works he found

himself in a position to help his relatives. But falling in

love with a young woman who was left a widow, he took her

for his wife, and had enough to do all the rest of his life,

and had to work harder than he had ever done before, for

besides the duties and liabilities which belong to such a

union, he took upon him many more troubles, being constantly

vexed with jealousy and one thing and another. And all who

knew his case felt compassion for him, and blamed the

simplicity which had reduced him to such a condition. He had

been much sought after by his friends before, but now he was

avoided. For though his pupils stayed with him, hoping to

learn something from him, there was not one, great or small,

who did not suffer by her evil words or blows during the

time he was there.

Nevertheless,

this torment seemed to him the highest pleasure. He never

put a woman in any picture which he did not draw from her,

for even if another sat to him, through seeing her

constantly and having drawn her so often, and, what is more,

having her impressed on his mind, it always came about that

the head resembled hers.

A

certain Florentine, Giovanni Battista Puccini, being

extraordinarily pleased with Andrea's work, charged him to

paint a picture of our Lady to send to France, but it was so

beautiful that he kept it himself and did not send it away.

However, trafficking constantly with France, and being

employed to send good pictures there, he gave Andrea another

picture to paint, a dead Christ supported by angels. When it

was done every one was so pleased with it that Andrea was

entreated to let it be engraved in Rome by Agostino

Veniziano, but as it did not succeed very well he would

never let any other of his pictures be engraved. The picture

itself gave no less pleasure to France than it had done in

Italy, and the king gave orders that Andrea should do

another, in consequence of which he resolved at his friend's

persuasion to go himself to France. But that year 1515 the

Florentines, hearing that Pope Leo X meant to honour his

native place with a visit, gave orders that he should be

received with great feasting, and such magnificent

decorations were prepared, with arches, statues, and other

ornaments, as had never been seen before, there being at

that time in the city a greater number of men of genius and

talent than there had ever been before. And what was most

admired was the façade of S. Maria del Fiore, made of wood

and painted with pictures by Andrea del Sarto, the

architecture being by Jacopo Sansovino, with some

bas-reliefs and statues, and the Pope pronounced that it

could not have been more beautiful it it had been in marble.

Meanwhile King Francis I, greatly admiring his works, was

told that Andrea would easily be persuaded to remove to

France and enter into his service; and the thing pleased the

king well. So he gave command that money should be paid him

for his journey; and Andrea set out joyfully for France,

taking with him Andrea Sguarzella his pupil. And having

arrived at the court, he was received lovingly by the king,

and before the first day was over experienced the liberality

of that magnanimous king, receiving gifts of money and rich

garments. He soon began to work and won the esteem of the

king and the whole court, being caressed by all, so that it

seemed to him he had passed from a state of extreme

unhappiness to the greatest felicity. among his first works

he painted from life the Dauphin, then only a few months

old, and therefore in swaddling clothes, and when he brought

it to the king he received for it three hundred crowns of

gold. And the king, that he might stay with him willingly,

ordered that great provision should be made for him, and

that he should want for nothing. But one day, while he was

working upon a St Jerome for the king's mother, there came

to him letters from Lucrezia his wife, whom he had left in

Florence, and she wrote that when he was away, although his

letters told her he was well, she could not cease from

worries and constant weeping, using many sweet words apt to

touch the heart of a man who loved her only too well, so

that the poor man was nearly beside himself when he read

that if he did not return soon her would find her dead. So

he prayed the king for leave to go to Florence and put his

affairs in order, and bring his wife to France, promising to

bring with him on his return pictures and sculptures of

price. The king, trusting him, gave him money for this

purpose, and Andrea swore on the gospels to return in a few

months. He arrived in Florence happily, and enjoyed himself

with his beautiful wife and friends. At last, the time

having come when he ought to return to the king, he found

himself in extremity, for he had spent on building and on

his pleasure his own money and the king's also. Nevertheless

he would have returned, but the tears and prayers of his

wife prevailed against his promise to the king. When he did

not return the king was so angered that for a long time he

would not look at a Florentine painter, and swore that if

ever Andrea fell into his hands, it should be to his hurt,

without regard to his talents.

Stopping on

my way cycling

home from Mass, I photographed these two pictures just

beyond and opposite the Santissima Annunziata

. . .

He returned to Florence. Here he was employed by Giacomo, a

Servite friar, who, when absolving a woman from a vow, had

commanded her to have the figure of our Lady painted over a

door in the Nunziata. Finding Andrea, he told him that he

had this money to spend, and although it was not much, it

would be well done of him to undertake it; and Andrea, being

soft-hearted, was prevailed upon by the father's

persuasions, and painted in fresco our Lady with the Child

in her arms, and St Joseph leaning on a sack. This picture

needs none to praise it, for all can see it to be a most

rare work.

One day Andrea had been painting the intendent of the monks

of Vallombrosa, and when the work was done some of the

colour was left over, and Andrea, taking a tile, called

Lucretia, his wife, and said, 'Come here, for as this colour

is left, I will paint you, that it may be seen how well you

are preserved for your age, and yet how you have changed and

how different you are from your first portraits'. But the

woman, having some fancy or other, would not sit still, and

Andrea, as if he guessed that he was near his end, took a

mirror and painted himself instead so well that the portrait

seems alive. This portrait is still in possession of

Lucrezia his wife.

The

gorgeous yellow silk is still spun, dyed and woven in

Florence.

See Antico Setificio

Fiorentino

. . .

After the seige was over, Florence was filled with the

soldiers from the camp, and some of the spearmen being ill

with the plague caused no little panic in the city, and in a

short time the infection spread. Either from the fear

excited by it, or from having committed some excess in

eating after the privations of the siege, Andrea one day

fell ill, and taking to his bed, he died, it is said, almost

without any one perceiving it, without medicine and without

much care, for his wife kept as far from him as she could

for fear of the plague.

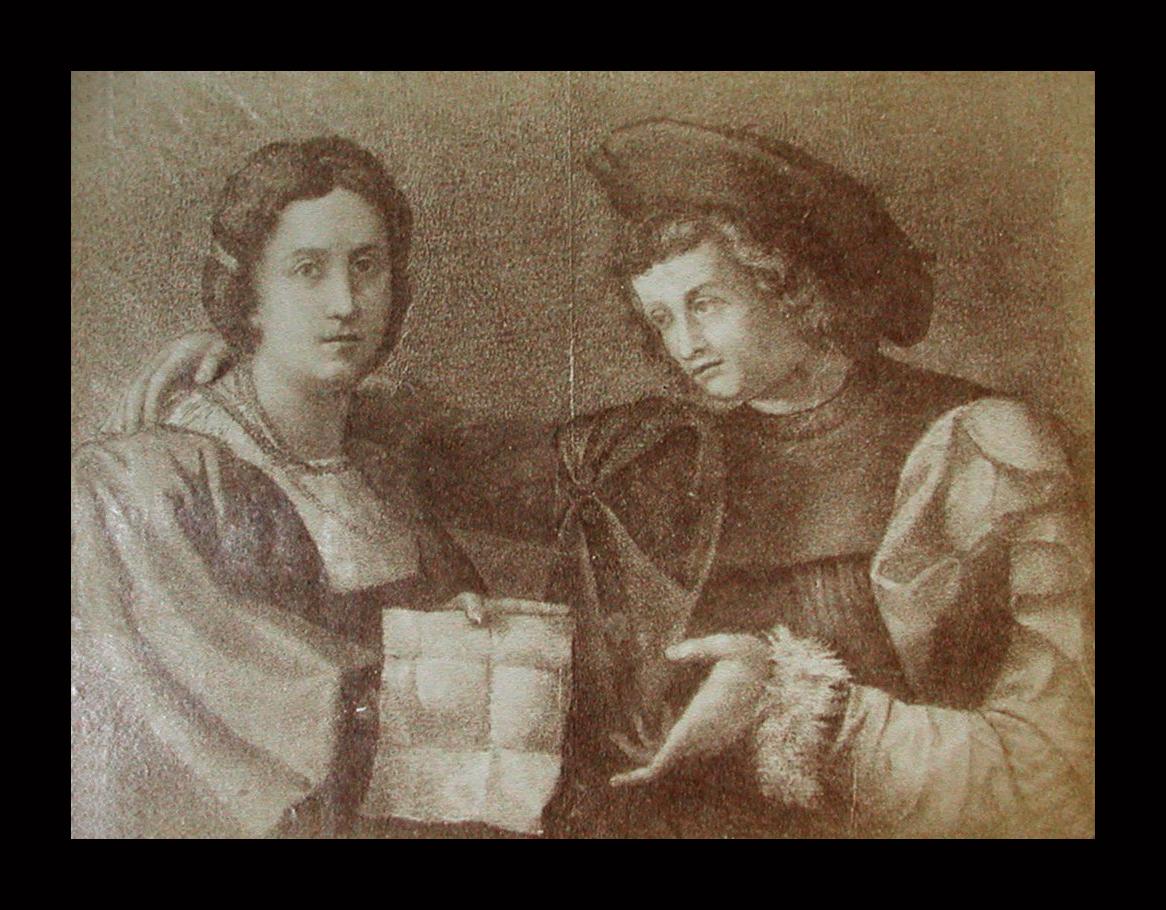

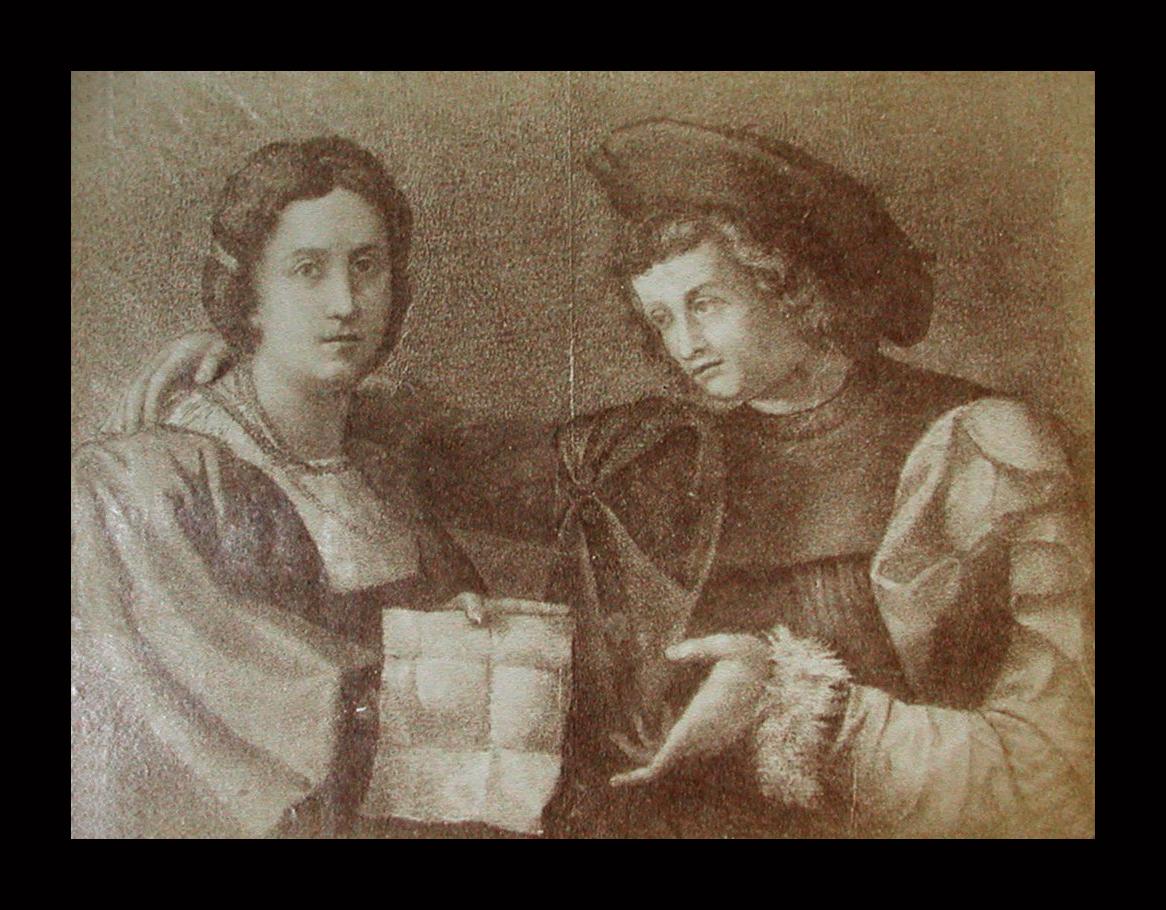

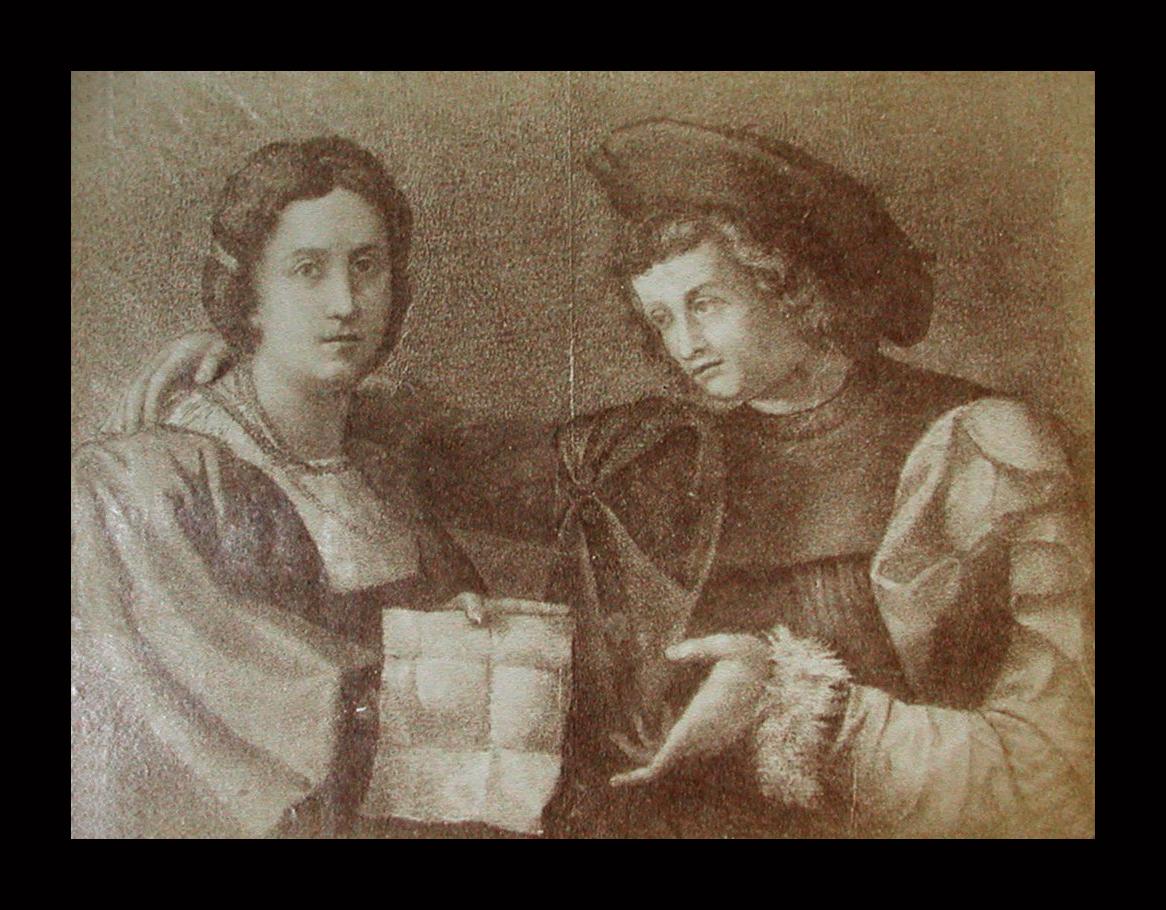

N. 15934. Galleria Pitti. Ritratto di Andrea del

Sarto e di Lucrezia del Fede sua moglie. Andrea del Sarto.

For larger image, click here

Giorgio Vasari

tells the story of his maestro,

with loathing for the wife, though he himself was also to marry,

and to marry happily. The voice in this account is

Vasari's and not Andrea's. Vasari's Andrea foolishly

adores his wife. Browning's Andrea deeply resents Lucrezia. I

would argue that the voice in the Victorian poem is not only

that of Browning's 'Andrea' but is that of Browning himself, of

a Browning deeply resenting Elizabeth's greater fame during her

lifetime, and that Robert Browning has thus constructed of

Andrea Del Sarto's double portrait his own 'Portrait of a

Marriage'. Reverberating with these portraits of wives is also

that of Browning's 'My Last Duchess'. For which see 'An Old Yellow Book'.

Andrea Del

Sarto, John the Baptist, Last Supper, Madonna of the

Harpies, Woman with 'Petrarchino', Holy Family

Michele Gordigiani, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett

Browning. Commissioned by the American Spiritualist Sophia

Eckley.

Michele Gordigiani's studio is in Piazzale Donatello, next

to the 'English' Cemetery where EBB is buried.

Andrea del Sarto and Lucrezia del Fede, in his Studio

beside the Santissima Annunziata, close to Porta a' Pinti

FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2022: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII

, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New: Opere

Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence