BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI

II. BROWN INK, RED BLOOD

BRUNETTO LATINO AND THE

SICILIAN VESPERS1

i Livres dou

Tresor, written by Brunetto Latino before June of 1265

as a presentation volume, contains a careful account of the

oath of office sworn by a podestà, in this instance, by

Charles of Anjou at his inauguration as Senator of Rome.2

Arnolfo di Cambio,

Charles of Anjou

Arnolfo di Cambio,

Charles of Anjou

Contemporary with this book is a statue by Arnolfo di Cambio, again presenting Charles of Anjou at his investiture as Senator. It shows him in a Roman toga clutching in his hand the capituli, the constitution, of Rome which he must swear to uphold.3 These two artifacts, a document and a monument which witness and record a legal speech act, are worthy of our study.

Of even greater interest and concern is that when Charles of Anjou failed to comply with his oath of office, further documents and monuments, in brown ink, and even red blood spilled in a Palermo square, record his downfall by means of the Sicilian Vespers, plotted against him by several Popes and an Emperor and by the Genoese, Pisans, Sienese, Aragonese, Sicilians, and Florentines. I will attempt to demonstrate Brunetto Latino's possible secret diplomacy and complicity in this affair, with documents in archives associated with and naming Brunetto, and with accounts of the Vespers plotting found in Latino manuscripts.

I

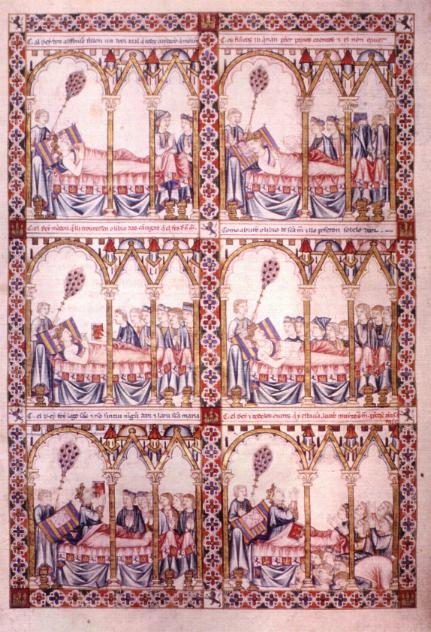

Florence, Las Cantigas,

The Miracle of the Cantigas

Florence, Las Cantigas,

The Miracle of the Cantigas

But Latino's embassy was too late. On September 4, Guelf Florence was utterly routed at Montaperti, the Arbia river being stained with blood.13 Brunetto wrote that he learned of the sentence of exile while journeying back through the Pass of Roncesvalles, a student from Bologna telling him the news. We also have a floridly written, grief-stricken letter from his father which begins: "Bonaccursius latinus de florencia dilecto filio Bornecto notario, ad excellentissimum dominum Alfonsum romanorum et hyspanorum regem iamdudum pro comuni florentie destinato, salutem. . ." and which goes on to narrate of the battle and the sentence of exile passed against their family.14 Brunetto's father, Bonaccursus Latinus, was likewise a notary.15 The father worked for the Guelf bishops of Fiesole; the son for the Guelf comune of Florence. Now both were driven into exile, the father perhaps only to Lucca's San Frediano district, the son first going to Montpellier,16 then Arras and Bar-sur-Aube, being associated in those places with Lombard banking houses whose tentacles reached out as far as the Baltic, the British Isles, and elsewhere.

II

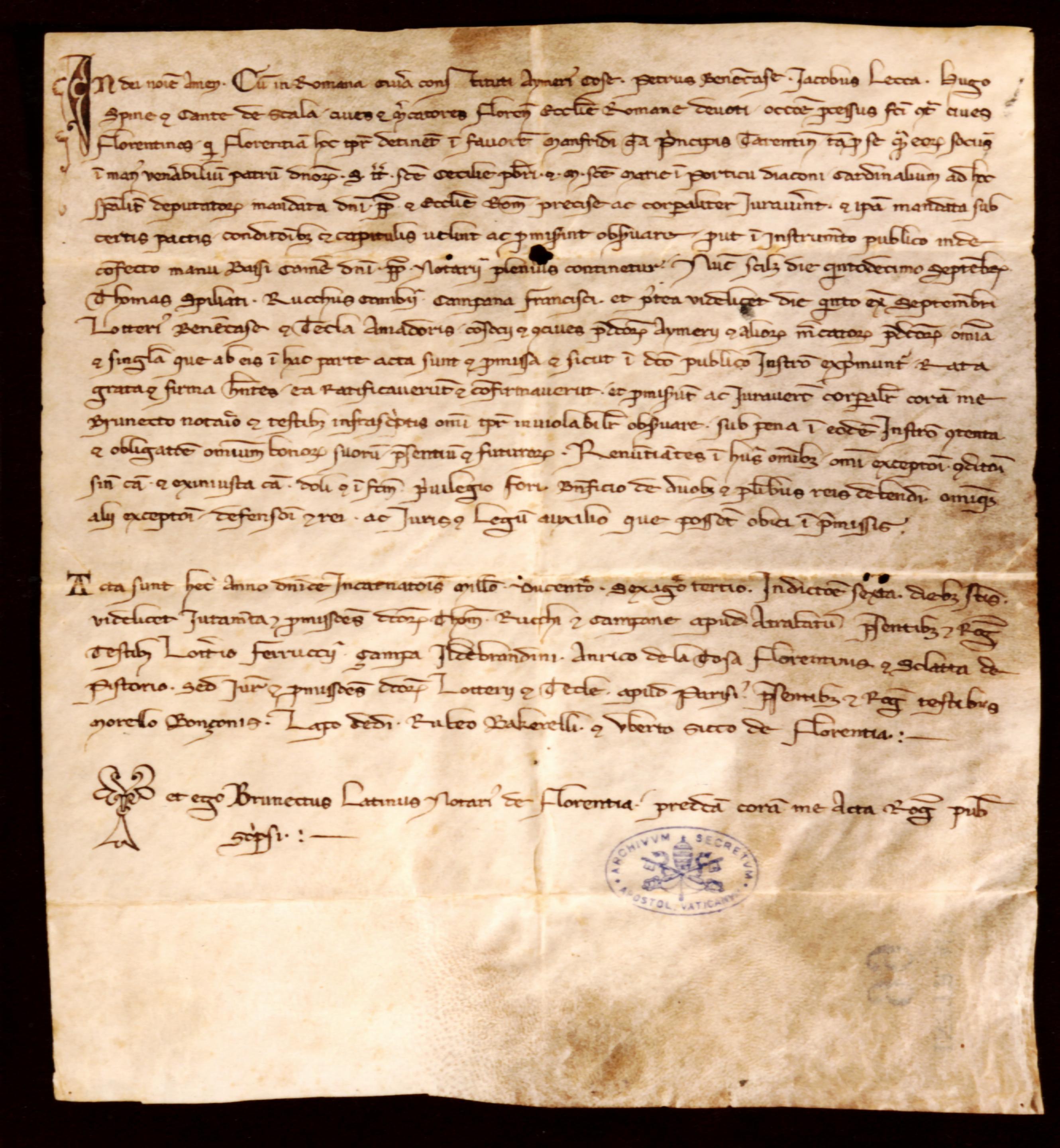

The first letter was written to the Roman Curia from Arras about notarized events on September 15 and 24 concerning these dealings and promised the loyalty of the exiled Florentine bankers in Arras and in Paris to the Pope's cause against Manfred, "quondam principis Tarentini."18 It named major Florentine bankers.19 Villani likewise explained that the exiled Guelfs joined Charles of Anjou and Pope Clement against Manfred.20

The second letter, written from Bar-sur-Aube to England, and still at Westminster Abbey, directly concerned England's payment of the crusading decima. It contracted between the Bellindoti and Spinelli family members and other Florentine merchants and bankers to loan almost two thousand marks sterling for the Bishop of Hereford's payment to the Roman Curia.21 An extraordinary sentence in the document states that to borrow at interest from the Florentines had papal approval, that such usury even brought (or, rather, bought) the crusading indulgence. There is a possibility that this was the amount, two thousand marks sterling, that the Curia arranged to pay to Lucca for sheltering the exiled Florentine Guelfs in the parish of San Frediano.22 The Florentine Guelfs, in reprisal for Montaperti, had already been able to have the English crown expel Sienese merchants from England.23 Besides these legal, political and financial documents, Brunetto, when in political exile, shaped major literary works, the Tesoretto, the dream vision poem that was to be the prototype for Dante's Commedia, and the Rettorica in Italian, and Li livres dou Tresor, the great encyclopedic work, in Picard French, the dialect of the Arras region, of Artois and Picardy.24

The Tresor included within its text the information that it was partly compiled from Brunetto's own researches into curial, legal archives. When Latino discussed the historical relationship between Pope and Emperor, he carefully stated that his information came from studying the papal registers: "Or dist l'istore, et li registre de sainte eglise le temoignent . . . ."25 It continued with the presentation at the core of the section on "Politica" of the seminal letter to Charles of Anjou, asking him to take up the office of Senator of Rome, being hired as a podestà to counter Ghibelline Manfred.

In the first redaction manuscripts Brunetto wrote that since Frederick there had been no real Emperor and that Frederick's son Manfred, born out of wedlock, had seized the kingdoms of Apulia and Sicily against God, Law, and Holy Church and that he had persecuted the Italians, especially the Florentine Guelfs, who were loyal to the Church. He added, within the text, that for this reason "Maistre Brunet Latin" was in exile in France where he was writing this book for love of his patron, Charles of Anjou and Provence. Later, when that friend was to prove instead an enemy, Brunetto was to rewrite that sentence, in Italian, as "for love of his enemy," "per amore del suo nemico."26 The exiled Florentine Guelf bankers needed a champion. They chose Charles, Count of Anjou and Provence, Senator of Rome, King of Sicily and Jerusalem and aspirant to the Greek Empire, over Alfonso el Sabio, King of Castile, aspirant to the Roman Empire, and Richard of Cornwall, likewise aspirant to the Roman Empire.27 All three men wished to be Emperors. Florentine bankers both tempted and foiled them. While the Tesoretto was likely written to Alfonso el Sabio, the Tresor was for Charles of Anjou. Therefore this work had to be written in French as Charles refused to learn Italian. But in the work Brunetto carefully attempted to teach his kingly reader about Italian forms of government, about republican comuni and of the hiring of a podestÿag, in this way telling Florence's new king how Florence should be governed, with as much republican freedom as possible. He was being an Aristotle to an Alexander.

The work contains a letter, written as if from the Roman Senate to Charles of Anjou and Provence, requesting him to be Senator of Rome, as podestà, for one year. The Tresor therefore can be dated as being written prior to June, 1265, when Charles did in fact become invested as Senator for life.28 This letter reversed the usual medieval and feudal stance of subject to ruler and instead was the ancient and modern citizen arranging for the employment of a podestà by a comune, a president who must take the oath of office to uphold the constitution and its laws. Into this letter Latino poured all of his political theory and ethical philosophy. In it he stated that men naturally desire freedom but that greed caused damage and destruction and that a just ruler was necessary to advance good men and to curb the malice of evil men. He went on to state that Charles should come to the Capitoline and there receive the books of the Constitution and likewise ten thousand livres in salary and that he should bring with him ten judges and twelve good and loyal notaries. He next stated that within three days Charles must make his decision whether to take or leave the seignory.

A companion work, not on parchment inscribed with a pen, but in marble, sculpted with chisels, is the statue by Arnolfo di Cambio, architect of both the Palazzo Vecchio and Poppi Castle, showing Charles of Anjou seated upon a red lion throne, in a white senatorial toga, the capitoli of Rome clasped in his hand.29 Saint Priest tells us that Charles was actually so dressed when he made his oath of office in the Franciscan church of Ara Coeli on the Capitoline in June, 1265.30 In this book of the Tresor, combining Cicero and Aristotle, and in this statue, shaped likewise by such perceptions derived from the political and legal practices of Rome, as well as in the dramatically staged inaugural itself, we can see the germs of the Florentine Renaissance. Florentine bankers and their lawyers, when in exile, were manipulating time and space to enact a drama of freedom to counteract their fear that it could be a representation and actuality, which it was, of power and oppression. Then, on January 6, Charles and his wife, Beatrice, the daughter of Raymond Berengar of Provence, were crowned King and Queen of Sicily and Apulia by the Pope in the Vatican.31 No one was going to let Charles of Anjou be Emperor of Rome.

III

Charles oppressed the people whom he governed at the Popes' pleasure, drawing upon himself papal criticism for his harshness. Clement IV had written to Charles in 1268 protesting his cruelty to Conradin and to women and children and his refusal to heed advice, counsel, and parliament.39 Gregory X sought union with the Greeks, a policy that was not favorable to Charles who wished, personally, to regain the Emperor Baldwin's now lost domain through yet another Crusade against fellow Christians. The crusade, for which he raised the decima, especially from his Sicilian subjects, was intended not to regain Jerusalem but Constantinople, to conquer back that Greek Christian kingdom from Michael Paleologus which the Latin Baldwin had previously held. Nicholas III, like Gregory X, also sought union with the Greeks, sending a legation to them of Franciscans with letters concerning Charles, and openly attacked Charles, taking from him the title of Senator of Rome and the Vicariate of Tuscany, and he attempted to make peace between the Guelf and Ghibelline factions.40 Finally the Peace of Cardinal Latino, with the Florentine bankers' strong support, succeeded in bringing together and reconciling Guelf and Ghibelline in Florence, much against Charles' will, who had insisted on punishing with great severity Ghibelline leaders, removing from them their right feet and hands, gouging out their right eyes, and incarcerating them in perpetuity.41

In 1281 the Florentines wrote to the Vicar of the Emperor Rudulph, stating in no uncertain terms that the comune recognized no emperor.42 Behind the scenes diplomacy was being carried out between the Emperor Michael Paleologus of Constantinople and King Peter of Aragon, to undermine Charles' crusade preparations.43 Then, on Easter Monday, 1282, the Sicilian Vespers broke out against Charles in Palermo. In the Latin diplomatic documents it is clear that the Sicilian Vespers revolt against Charles of Anjou was not spontaneous but deliberately planned, was not a revolution by oppressed subjects against a king, but instigated with care by popes and emperors and carried out by republicans and aristocrats. It is not generally considered that Florence was in any way involved in these plots.

In a third of the 36 Italian manuscript translations of the Tresor, the Tesoro, are careful accounts, in three different versions, edited by Michele Amari as I, II, and III,44 the more complete giving the diplomatic letters and first-hand accounts of secret conversations involving Gianni di Procita (Giovanni da Procida, John of Procida), the Neapolitan Knight, Physician, and Chancellor of Aragon, and an Accardo Latino who, disguised as Franciscans, journey between the Emperor Michael in Constantinople, the Pope, King Peter of Aragon, and the Sicilian noblemen in exile in Africa plotting the Vespers.45 One of these accounts gives the Giuseppe Verdi version concerning the French assault upon the Sicilian woman as provocation, the other two that the Sicilian Vespers occurred as a tax revolt against the decima payments for Charles' Crusade to conquer Constantinople. In the Crown Archives of Aragon we find documents from the Procidas to Alfonso el Sabio concerning this diplomacy.46 Brunetto's father, Bonaccursus Latinus, worked for Filippo Perusgio, the Bishop of Fiesole who had initially gone on embassy for the Pope to the Greek Emperor.47 In Villani's Cronica and in Dante's Commedia this knowledge is present and its account is further substantiated. See, for instance, where Dante chastises Pope Nicholas for accepting the money conveyed to him by these two agents from the Emperor Michael Paleologus to counter Charles of Anjou:

Però ti sta, chè tu se' ben punito;And where he describes the Sicilian Vespers uprising that money paid for:

e guarda ben la mal tolta moneta

ch'esser ti fece contra Carlo ardito.Inf. XIX.97-99[But you are here, because you are well punished; and guard well the ill-taken money that made you bold against Charles.]

E la bella Trinacria . . .Palermo, Sicily, http://www.regione.sicilia.it/beniculturali/bibliotecacentrale/tesori/immagini/t58a.jpg, gives a digital excerpt from the Sicilian account of the Sicilian Vespers, matched in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze's Brunetto Latino Tesoro manuscript in Tuscan Italian.

attesi avrebbe li suoi regi ancora,

nati per me di Carlo e di Ridolfo,

se mala segnoria, che sempre accora

li popoli suggetti, non avesse

mosse Palermo a gridae: "Mora, mora!" Par. VIII.67-75[And the beautiful Trinacria . . . which would still await its kings, born from me of Charles and of Rudulph, if bad governing which always disturbs subjected peoples, had not moved Palermo to cry, "Death, Death!"]

Given this evidence, I believe that Accardo Latino could be Brunetto Latino, encouraged by his father and delegated by Cardinal Latino, to carry out this diplomacy by the Guelfs and the Popes opposing Charles.48 My reasons for this belief are Brunetto's participation with other poets in a series of tenzoni written against Charles,49 the Epistolaria manuscripts which include Pier delle Vigne's letters followed by those of Brunetto on the Abbot Tesauro of Vallombrosa, Popes fulminating against Charles for his injustice to his people, and the letter of the Comune of Palermo to that of Messina, written in the style of Primo Popolo letters also included in these collections,50 the Latino Sommetta which includes the notarial formula to be used by the Popes and the Emperor when writing to Charles of Anjou, Alfonso el Sabio, Archbishop Ruggieri of Pisa and others,51 the several accounts of the Sicilian Vespers' secret diplomacy which occur in so many of the Italian Tesoro manuscripts,52 the proliferation of Latino material, in one case bound with yet another account of the Vespers, in Catalan in the kingdom of Aragon,53 the continuing involvement of the Latino family with the houses of Aragon and Anjou,54 and Dante Alighieri and Giovanni Villani's knowledge of the complicity.55

Following immediately upon the Sicilian Vespers the new constitutional structure of Florentine government, the Priorate, was established - as if the one led to the other. This structure was based on the election of twelve Priors (reminiscent of the Latino letter in the Tresor concerning ten, or in the Italian version twelve, judges and twelve notaries), who were elected for a two month term of office, living, during that period, locked up in the Torre della Castagna, beyond the reach of corrupting influence. Dino Compagni, who as a young man had been involved in drawing up this restructuring of Florentine government, gave a careful account of it in his Cronica, Giovanni Villani noting that "Prior," as concept, came from Christ's "Vos estis Priores," to his disciples. Brunetto Latino was to be one such Prior and Dante Alighieri, another. From this date until his death Brunetto was to be mentioned again and again, forty-two times between 1285 and 1292, in the Consulte or Libri Fabarum as advising on constitutional matters and secret diplomacy and as giving ringing speeches concerning republican, comunal freedom, speeches echoing those of Cicero against Catilina, on liberty.56

From this material a picture emerges of Florentine skill at maintaining and regaining her comunal liberties through a balancing of power, playing one imperial candidate off against another while plotting secretly to negate such imperial pretensions. One solution was that of the constitutionality of the ruler, who had to swear contractually to uphold the comune's laws as podestà for a limited term of office, a pattern Jefferson, perhaps through his Tuscan friend Philip Mazzei, was to make use of for the United States' office of the President.57

Interestingly, Brunetto Latino, who played such a central role in this deceptive diplomacy and in this constitutional development, was to be the teacher of Dante Alighieri, who in the dialectic and bitterness of his later exile would become Ghibelline, rather than Guelf, and would see monarchy and Virgilian Empire as the answer, rather than the Ciceronian Roman Republic, the Res publica, reflected in the Florentine comune. The disciple was for peace; the master, for freedom, libertas.

Notes

1 An initial version of this research appeared

in "Chancery and Comedy: Brunetto Latini and Dante

Alighieri," Lecture Dantis, 3 (1988), 73-94; this form

of the paper was read at the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium,

April 14, 1989, and critiqued by Richard Kay; a more complete

version is published in Twice-Told Tales: Brunetto Latino

and Dante Alighieri (New York: Peter Lang, 1993).

2 Li Livres dou Tresor, ed. Francis J.

Carmody (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1945),

III.ii.v, pp. 396-6.

3 Robert Davidsohn, Storia di Firenze,

trans. Giovanni Battista Klein (Florence: Sansoni, 1957), from

Geschichte von Florenz (Berlin: Mittler, 1896-1927),

III, 586-7, II, Plate 33, Roma, Palazzo dei Conservatori; Le

Comte Alexis de Saint-Priest, Histoire de la Conquete de

Naples par Charles d'Anjou, frère de Saint Louis (Paris:

Amyot, 1858), II, 149.

4 Demetrio Marzi, La Cancelleria della Repubblica

Fiorentina (Rocca S.

Casciano: Capelli, 1910), p. 35, claims Latino was first

"Dettatore e Cancelliere della Republica"; Daniela De Rosa

notes that this powerful office was not concentrated in any

one individual's control but instead shared by the notaries

during the Primo Popolo period.

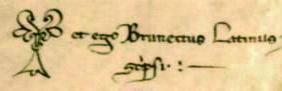

5 Brunetto is both named and his handwriting

appears in the Libro di Montaperti, published version,

(Libro di Montaperti (An MCCLX), ed. Cesare Paoli

(Florence: Vieusseux, 1889): 26 February, 1260, fol. 11, p.

34; 20 July, fol. 50v, p. 123; 22 July, fol. 65v, p. 148; 24

July, fol. 65v, p. 148; 23 July, fol. 74v, p. 172.

6 Davidsohn, II. 617-8, 687; Pisa

had sought aid, proposing Alfonso for Emperor in their

league with him against Lucca, Genova, Florence, 1256;

Vatican Secret Archives, Instr. Misc. 87, 1257/1268, "Articuli propositi a

procuratoribus Alphonsi regis Castellae coram Clem. IV. ad

probandum eius electionem in Regem Romanorum a nonullis

Electoribus Imperii facta an. 1257, contra Riccardum,

fratrem Regis Angliae, qui ab aliis Electoribus

inauguratus fuerat. Exemplar membr. 9 paginorum"; 1

February, 1264, Alfonso wrote to Pope requesting to be

crowned Emperor, Vatican Secret Archives, A.A. Arm. 1-18, n.

167, published in Bruno Katterbach and Carolus

Silva-Tarouca, Epistolae et Instrumentum saeculi XIII, in

Exempla scriptorum edita consilio et opera procuratorum

bibliothecae et tabularii vaticane, Fasc. II (Roma: 1930),

Table 22a; the Spanish bishop, Garcìa Silves, sent to the

Pope for this purpose, December, 1267, was murdered by the

Pazzi, mentioned, Inferno XII. 137-8; Instr. Misc. 46,

23 March, 1276: "Innocentius

PPV concedit Regi Castellae et Legionis ecclesiasticarum

decimarum . . . pro subsidio contra Saracenos. Bullo orig.

carens plumbo."

7 Villani, Istoria di Firenze (Florence, 1823; Rome:

Multigrafica Editrice, 1980), VI. lxxiv; repeated in ASF MS

225, fol. 9; Lapo da Castiglionchio, Laurentian Library,

LXI. 13, fols. 14v-15.

8 Brunetto Latini, Il Tesoretto, ed.

and trans. Julia Bolton Holloway (New York: Garland, 1981),

lines 113-162, Laurentian Strozziano 146, illumination, fol.

2.

9 Carmody, p. xvi, quoting

Schirrmacher, Geschichte

Castiliens im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert, ed. Friedrich Wilhelm Lembke (Gotha, 1881),

476, and Memorial

Historico Espanol, I

(Madrid, 1851), 134, on Alfonso's activities, who was in

Toledo, 2 February, Soria, 12 April, Cordova, 3-6 June,

Seville, 27 July, returning to Cordova, 20 September, while

Brunetto Latino is present in the Florentine Libro di Montaperti through July 24 and the Battle

of Montaperti took place on 4 September.

10 Las Siete

Partidas del rey don Alfonso el Sabio (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1807); "Titulo XXIV: De los romeros

et de los Peregrinos, Ley I," reads much like Dante's Vita Nuova definition of

pilgrims, perhaps relayed through Latino.

11 Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale,

Magl. II.VIII.36, fol. 75. This Tesoro

manuscript is possibly copied by Dante.

12 Biblioteca Nazionale, Banco

rari 20.

13 Dell' Historia di Siena

scritta da Orlando Malavolti (Venezia, 1599), end of first volume, "l'Arbia colorato in rossa."

14 F. Donati, "Lettere politiche

del secolo XIII sulla Guerra del 1260 fra Siena e Firenze,"

Bulletino senese di

storia patria, 3

(1896), 230-232, transcribing now war-destroyed Breslau

Library MS 342, document 73. My thanks to Anthony Luttrell

for this information.

15 Armando Petrucchi, Notarii: documenti per la

storia del Notariato italiano (Milan: Guiffré, 1958), p. 17, notes that fathers

trained sons as notaries.

16 Mentioned in Tesoretto, line 2451;

the Archives de la Ville de Montpellier: Inventaires et

Documents, III: Inventaires des Cartulaires de Montpellier,

(980-1789) (Montpellier: Serre et Roumégons, 1901-7),

pp. 101-2, #712, 715, 716, demonstrate importance of Italian

merchants there who linked that city with the great fair in

Champagne at Bar-sur-Aube.

17 Papal excommunication of the

Florentine Guelfs for this crime, Vatican lat. 4957, fol.

80. That murder generated a vicious paper war, one

magniloquent letter being sarcastically penned by Brunetto

in the Ghibelline style of Pier delle Vigne, Vatican lat.

4957, fol. 79. Fol. 90, letter from Siena to Richard of

Cornwall, using the murder of the Abbot Tesauro of

Vallombrosa as pretext for Montaperti: "Et, quod est prohanum audire . . . in

venerabilem patrem, vita sanctissimum Abbatem Vallis umbrose,

impias intulerent manus, amputandum sibi caput in publica

concione," Donati, "Lettere politiche," p. 264.

18 Vatican Secret Archives, Instr.

Misc. 99; M. Armellini, "Documento autografo di Brunetto

Latini relativo al ghibellini di Firenze scoperto negli

archivi della S. Sede," Rassegna italiana,

V/I (March, 1885), p. 359-363; Hans Foerster, Mittelalterliche Buch und

Urkundenschriften auf 50 Taflen mit Erlauterungen und

vollständinger Transkription (Berne: Haupt, 1946), Plate XXV, comments,

transcription, pp. 64-5; Katterbach and Silva-Tarouca, Epistolae et Instrumenti

saeculi XIII, p. 20,

Plate 21.

19 Aymeri Cose, Pietro and

Lotterio Benincase, Cavalcante della Scala, Tommaso

Spigliati, Ricco Cambi and Hugo Spine, some of whom had been

on embassy to the Roman Curia; many of these individuals

named in Brunetto's document for the Siena/Florentine peace

accord of 1254 and that at Orvieto ratifying it in halcyon

years before Montaperti: Gino Arias, "Sottomissione dei

banchieri fiorentine alla Chiesa, 9 dic., 1263," in Studi e Documenti di storia del

Diritto (Florence: Le

Monnier, 1901), pp. 114-120; E. Jordan, De Mercatoribus camerae

apostolicae saeculo XIII (Oberthur, 1909), notes that Thomas Spigliati was

associated with Arras, p. 97, speaks also of Hugo Spine, pp.

25-30; Siena document, exhibited and listed in Le Sale della Mostra della

Mostra e il Museo delle Tavolette dipinte, catalogo:

Publicazione degli Archivi di Stato XXIII (Rome: Ministero dell'interno,

1956), #6, p. 117; transcribed in Il Caleffo Vecchio del Comune di Siena, ed. Giovanni Cecchini

(Florence: Olschki, 1935), #567, II. 779.

20 "e mandarono loro ambasciadori a papa Clemente,

acciochè gli racomandasse al conte Carlo eletto re di Cicilia,

e profferendosi al servigio di santa Chiesa," VII.ii.

21 Westminster Abbey Muniment

12843, April 17, 1264. Peter de Egeblanke, Bishop of

Hereford, worked with the Curia and the Florentines in exile

after Montaperti, raising funds against Manfred, Davidsohn,

II, 608-9.

22 Davidsohn, II.754; III.30,

notes 1268 payment of 6000 marks sterling loaned by Lucca to

Charles, to be returned at fair of Bar-sur-Aube in Champagne

from France's crusading decima; II.607-9,701,741, also

discuss Mozzi-Spini and Spigliati, Ardinghelli, Aymeri Cose,

Curia and England relationship.

23 Letter of Andrea de Tolomei,

Troyes, 4 September, 1262, in Lettere volgare del secolo XIII scritte da

Senesi, ed. Cesare

Paoli, E. Piccolomini (Bologna: Romagnoli, 1871), p. 41,

cited in Donati, p. 259.

24 Christian Bec, Les marchands écrivains à

Florence, 1375-1434

(Paris: Mouton, 1967) gives later context of such merchant

bankers' literary milieu and production. My thanks to Judson

Boyce Allen for this information.

25 Tresor, ed. Carmody, p. 73.

26 Tesoro (Treviso: Flandrino, 1474),

caplo. lxxxxi. An important early Tesoro manuscript

gives this reading, Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana 42.19,

fol. 19, another, Bibl. Nazionale, Magl. II.VIII.36,

suppresses Charles' name.

27 Archivio di Stato di Firenze,

MS 225, fol 10, "Nel medesimo anno [1265]

Papa Urbano quarto per sodisfare à Guelfi di Toscana, fece

in Roma un gran concilio, nel quale privò Manfredi di Regni

di Sicilia, et di Puglia, et ne investa Carlo d'Angiò, et di

Provenza Fratello del Re Luigi di Francia"; fol. 10v, "Nel detto tempo i Guelfi

usciti di Firenze mandarono à Papa Clement à offeriva in

servizio di s[anc]ta Chiesa per essere raccomandate . . .

Conte Carlo nuovo Re di Sicilia."

28 Tresor, pp. 396-7. Carmody, p. xviii,

doubted the importance of the letter, despite Davidsohn;

perhaps because E. Jordan, Les origines de la domination angevine en Italie (Paris: Picard, 1909), p. 458,

had discounted it: "Je ne tiens pas de compte de la lettre

des Romains à Charles d'Anjou, inserée dans le Tresor de Brunetto Latino. Contrairement à

l'opinion de Sternfeld, Karl von Anjou als Graf der

Provence, 183, n. 2, elle me semble etre un simple exercise

de style. La preuve en est qu'elle parle d'une élection pour

un an, alors que nous savons que le comte fut élu à vie."

29 Davidsohn, III. 586-7; II,

Plate 33, Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori.

30 Saint Priest, II. 149.

31 Michele Amari, La guerra del Vespro siciliano (Paris: Baudry, 1845), I,

46-47. In his place Charles made Henry, the traitor exile

brother to Alfonso X el Sabio of Castile, Senator of Rome.

True to his treacherous nature, Henry was to welcome and

recieve the young Conradin in Rome: Charles-Joseph Hefele, Histoires des Conciles, trans. H. Leclercq (Paris:

Letouzey, 1914), VI, 57.

32 Davidsohn, III. 116, 149; ASS

Cons. gener. 19, fol. 9v. My thanks to Daniela De Rosa who

read the document in question and noted that the discussion

continues through folios 4v, 24v, 42, 57v-58.

33 Amari, Vespro

siciliano, II, 365-6, giving Naples Archives, segn.

1283, Reg. Carlo I, A, fol. 130, as source. The Archives in

Naples were destroyed by fire, 1944. However, Palermo, Bibl.

Com. Qq Gl and Rome, Bibl. Angelica D.VIII.17 transcribed

documents relating to Sicily and Charles. The documents

survive, Genova, Liber Iurum Reipublicae Genevensis II,

in Historia Patriae Monumentum (Torino, 1836-84), II,

cols. 60 ff, transcribing 13-21 October, 1284; Codex A, fols.

437-441; ASG Codex C, fols. 126-131; #424, Busta 6/42; ASF

Capitoli di Firenze, 43 (formerly XLIV/XLVI), fols. 29-39,

Brunetto Latino named, fols. 34, 37v, 38. The deaths of

Ugolino and his progeny by starvation as a result of

Florentine plotting concerning Pisa will possibly cause the

establishment of Orsanmichele as a granary for famine.

34 Runciman, pp. 206-7.

35 Phrases found in rhetoric

associated with Gianni di Procita against Charles passim, in

Palermo and Biblioteca Angelica manuscripts and in Tesoro Sicilian Vespers accounts.

36 Saint Priest, II. 28.

37 Amari, Vespro siciliano, p. 115; Tesoro account

of Vespers ends with moving lament of Count Jordan, who

desires death rather than his continuing misery and who

addresses his severed hand which had dubbed so many fair

knights.

38 Purgatorio XX. 61-69.

39 Palermo, Bibl. Com., Qq Gl, fols. 100v-102;

Hefele, Histoire des Conciles, VI. 59.

40 Hefele, Histoires des Conciles, VI. 153-268; Vatican Secret

Archives, Instr. Misc. 157, 158, 159, 160, 592; Gaetano

Salvemini, Magnati e

Popolani in Firenze dal 1280 al 1295 (Florence:

Carnasecchi, 1899), p. 19; Latino's Sommetta

gives the notarial formulae for Nicholas III to use when

writing to Charles of Anjou and Alfonso el Sabio.

41 See Amari, Vespro siciliano, p. 115.

42 Richard Kay, Dante's

Swift and Strong: Essays on 'Inferno' XV (Lawrence:

Regents Press of Kansas, 1978), p. 21, who states the letter

is Brunetto's.

43 G. Villani,

VII.lvii, p. 236, mentions letter sent from Pope to Aragon as

sealed with his seal as Cardinal; Genoese pergamene for this

period demonstrate that Genoa and the Florentines were in

contact with the Greek Empire against Charles of Anjou;

Pasquale Lisciandrelli, Trattati e negoziazione politiche

della repubblica di Genova (958-1797) (Genova: Società

ligure di storia patria, 1960), #338, Archivio di Stato di

Genova, Busta 5/20, also 5/38,39,40, 1261, Genova with Manfred

of Sicily, Michael Paleologus of Constantinople, 10 July,

Alfonso el Sabio, 1262, 15 & 16 August, Charles of Anjou,

21 July; 1273, February 7, #383, Busta 6/2, on Genoese

ambassadors making agreement with Pope at Orvieto and with

Venice to oppose Charles on electing King of Bohemia Emperor;

1275, Genova and Greek Emperor ratified l26l accords (Busta

3/39) between the two states, #415, Busta 6/34, that agreement

being made February 7, 1281, for five years or longer; Vatican

Secret Archives and Crown Archives of Aragon similarly

demonstrate friendly relations between these Latin states and

the Greek Empire, countering Charles' ambitions. The Vatican

material stresses need for Greek speakers to be present in the

delegations, Instr. Misc. 160, 592, 30 November, 1276. Paris,

Bibliothèque Nationale lat. 4042, gives Pier delle Vigne,

Brunetto Latino/Tesauro and Sicilian Vespers letters, fols.

92v-95v, colophon noting it was compiled as a "summa

dictaminis" by Thomas of Capua, notary of the Roman Curia,

1294. Meanwhile, Brunetto's texts proliferate in Catalonia and

Aragon, as well as in Castile and Andalusia, demonstrating his

access to both Alfonso el Sabio and to Peter of Aragon. See

Deno Geanakoplos, Emperor Michael Paleologus and the West,

1258-1282: A Study in Byzantine Latin Relations

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959).

44 Manuscripts,

Siglum A, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, G 75 sup. Amari I; As,

Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Ashburnham 540, Amari I, Br,

London, British Library, Addit. 26105, Cronica to

1285; De Visiani, lost MS, Amari I; F4, Florence, BN, Magl.

VIII.1375, Amari III, corresponding with Sicilian Lu

Rebellamentu di Sichilia, ed. Sicardi; G1, Florence,

Bibl. Laur. Gaddiano 26, Amari II; G2, Bibl. Laur. Gaddiano

83, Amari II; L1, Bibl. Laur. 42.20, Amari II; L4, Bibl. Laur.

42.23, Amari I; R1, Florence, Bibl. Riccardiana, 2221, Amari

I; S, San Daniele del Friuli, Bibl. Communale, 238, Amari II;

V1, Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, lat. 5908, Amari II; while

1286 Florence, BN, Magl. II.VIII.36, speaks of Tesoro

written for love of his enemy.

45 The

neo-Ghibelline Michele Amari edited these accounts in Altre

narrazione del Vespro siciliano scritte nel buon secolo

della lingua (Milano: Hoepli, 1887), disbelieving

Brunetto's authorship. Enrico Sicardi also published them in

their Sicilian versions, Due Chronache del Vespro in

volgare siciliano del Secolo XIII, in L. A. Muratori, Rerum

Italicarum Scriptores: Raccolta degli storici italiani

(Bologna: Zanichelli, 1917) 39.91-126. Geanakoplos, Michaal

Paleologus, cites De Michaele et Andronico

Paleologis, ed. I. Dekker (Bonn, 1835), 2 vols, George

Pachymeres' contemporary Byzantine history, speaking of use by

these delegates of Franciscan disguises. A chronicle account

of the Sicilian Vespers also occurs with a Catalan Tesoro

manuscript, Biblioteca Seminar Conciliar de Barcelona, MS. 74.

Professor Richard Kay does not believe in a Brunetto Latino,

Accardo Latino, Sicilian Vespers connection.

46 Isidoro

Carini, Gli Archivi e le Biblioteche di Spagna in rapporto

alla storia d'Italia e di Sicilia in particolare

(Palermo: Statuto, 1884), II, 45-46, giving February, 1280, 1

April, 1282, 19 May, 1282, apologies from Giovanni di Procita

to Alfonso el Sabio.

47 Davidsohn,

III, 210-211; Vatican Secret Archives, Instr. Misc. 157, 158,

159, 160, 592; Archivio vescovile della Diocesi di Fiesole MS

II.B.4, Atti, prefaced by verses by "Bonaccursi di Lastra" to

"Phylippus Perugine"; Scipione Ammirato, Vescovi di

Fiesole, di Volterra, et d'Arezzo (Florence, 1637), pp.

28-29.

48 Geanakoplos,

p. 292, citing M. Laurent, Innocent V, 411, notes that

a pass issued by Charles for one member of this delegation was

for a mysterious "L." He also mentions the Greek documents as

citing a "Calado" or "Kladas" as being involved. Bartholomeus

de Neocastro, Historia Sicula, in Lodovico Antonius

Muratorius, Rerum Italicum Scriptores (Milano, 1728),

III, col. 1049, notes: "Et

Carolus Rex . . . staret pedibus ante Ecclesiam . . . Magister

Bonaccursus tenta balista terribili in eum projiciens." Is this a Latino relative taking pot shots

at his king?

49 Vatican 3793

contains tenzoni of Palamidesse Bellindoti, Guglielmo

Beroardi, Rustico di Filippo, Brunetto Latino, etc. Another

appears on the flyleaf of a Ferrara Tresor manuscript,

along with a Dante sonnet to Guido Cavalcanti, Biblioteca

Comunale Ariostea, II.280.

50 Paris, BN,

lat 4042, fols. 92v-95v; Palermo, Biblioteca Comunale Qq G1.

51 Florence,

Biblioteca Nazionale, Magl. II.VIII.36, fol. 75.

52 Published in

Michele Amari, Altre narrazioni; Due Cronache del

Vespro in volgare siciliano del Secolo XIII, ed. Enrico

Sicardi, in L. A. Muratori, 39.91-126.

53 Biblioteca

Episcopal del Seminar Conciliar de Barcelona, 74.

54 Two of

Brunetto's sons, Bonaccursus and Perusgio (Perseo), were to be

involved with the Angevin court of Robert of Naples, the first

as Florence's ambassador, the second as courtier. The

Bonaccursi family were bankers in Naples and elsehwere until

their bank failed, 1312, Romolo Caggese, Roberto d'Angiò e

i suoi tempi (Florence: Bemporad, 1922), I, 598. Perseo

would be given the lilies of Anjou for his coat of arms to add

to his father's of six roses.

55Inf.

XIX.97-99; Par. VIII.67-75; G. Villani, VII.liv, p.

227.

56Le Consulte

della Repubblica Florentina dall'anno MCCLXXX al MCCXCVIII (Florence:

Sansoni, 1898), publishing the ASF Libri Fabarum, and

Documenti dell'Antica Costituzione del Comune di Firenze:

Appendice: Parte Prima, 1251-1260, ed. Pietro Santini

(Florence: Olschki, 1952), give many of the documents

associated with Brunetto.

57 Another member

of the Mazzei family erected the memorial tablet to Brunetto

Latino in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore above his

restored tomb:

BVRNETTO.LATINO.PATRITIO.FIORENTINO/ELOQVENTIA.AC.POESEOS.

RESTAVRATORI/ DANTIS.ALIGHERII.ET.GVIDONIS.CAVALCANTIS/MAGISTRO.

INCOMPARABILI.QVI.OBIT.AN.DOM.MCCLXXXXIV/HANC.EIVS.SEPVLCHI.

COLUMELLAM.DEPERDITAM/HVIVS.COENOBI.PATRES/ADNVENTE.P.M.IOSEPHO.

MARIA.MAZZEIO.VIC.GENERALI/RESTITVTO.FLORENTINIS.CIVIBVS.TANTO.

SPLENDORE/AD.P.R.M.PONENDAM.CVRARVNT.AN.D.MDCCCLI."

Go to:

Brunetto Latino and Dante Alighieri

I Bankers

and Their Books: Italian Manuscripts in French Exile

II Brown Ink, Red Blood:

Brunetto Latino and the Sicilian Vespers

III The

Vita Nuova's Pilgrimage Paradigms

IV

Stealing Hercules' Club: Inferno XXV's Metamorphoses

Geoffrey Chaucer

V Black and

Red Letter Chaucer

VI Fact

and Fiction: Women in Love

VII

Convents, Courts and Colleges

VIII The

Tomb of the Duchess Alice

Terence, Dante,

Boccaccio and Chaucer

IX God's Plenty: Terence in Dante,

Boccaccio, Chaucer and

Shakespeare Newest

| To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's

formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library

click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's

PayPal button: THANKYOU! |