611 Firenze. R. Galleria Uffizi. La Fortezza (Botticelli)

For larger image, click here

FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN: WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

JOHN RUSKIN

MORNINGS IN FLORENCE III

THIRD MORNING

BEFORE THE SOLDAN

611

Firenze. R. Galleria Uffizi. La Fortezza (Botticelli)

For larger image, click

here

[Botticelli, Fortitude, Judith, Fra Angelico,

Santa Croce, de' Bardi Chapel]

![]() PROMISED some note of Sandro's Fortitude,

before whom I asked you to sit and read the end of my last

letter; and I've lost my own notes about her, and forget, now,

whether she has a sword, or a mace;—it does not matter. What

is chiefly notable in her is—that you would not, if you had to

guess who she was, take her for Fortitude at all. Everybody

else's Fortitudes announce themselves clearly and proudly.

They have tower-like shields, and lion-like helmets—and stand

firm astride on their legs,—and are confidently ready for all

comers. Yes;—that is your common Fortitude. Very grand, though

common. But not the highest, by any means.

PROMISED some note of Sandro's Fortitude,

before whom I asked you to sit and read the end of my last

letter; and I've lost my own notes about her, and forget, now,

whether she has a sword, or a mace;—it does not matter. What

is chiefly notable in her is—that you would not, if you had to

guess who she was, take her for Fortitude at all. Everybody

else's Fortitudes announce themselves clearly and proudly.

They have tower-like shields, and lion-like helmets—and stand

firm astride on their legs,—and are confidently ready for all

comers. Yes;—that is your common Fortitude. Very grand, though

common. But not the highest, by any means.

Ready for all comers,

and a match for them,—thinks the universal Fortitude;—no

thanks to her for standing so steady, then!

But Botticelli's

Fortitude is no match, it may be, for any that are coming.

Worn, somewhat; and not a little weary, instead of standing

ready for all comers, she is sitting,—apparently in reverie,

her fingers playing restlessly and idly—nay, I think—even

nervously, about the hilt of her sword.

For her battle is not to

begin to-day; nor did it begin yesterday. Many a morn and eve

have passed since it began—and now—is this to be the ending

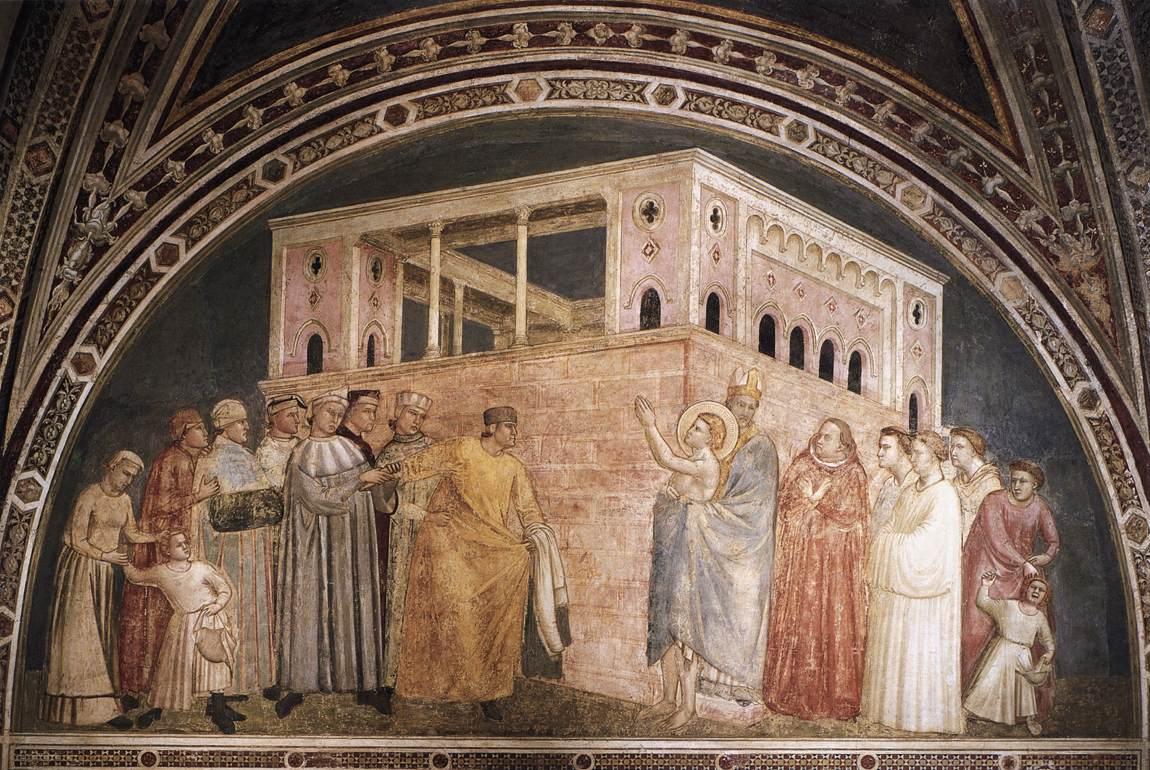

day of it? And if this—by what manner of end?

That is what Sandro's

Fortitude is thinking. And the playing fingers about the

sword-hilt would fain let it fall, if it might be: and yet,

how swiftly and gladly will they close on it, when the far-off

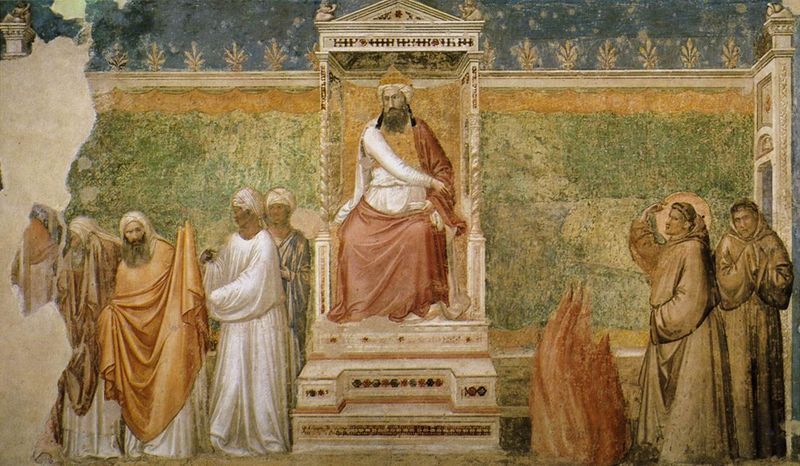

trumpet blows, which she will hear through all her reverie!

39. There is yet another

picture of Sandro's here, which you must look at before going

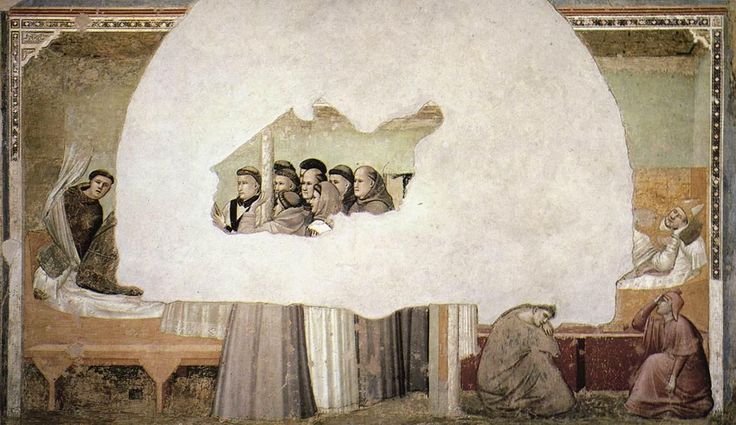

back to Giotto: the small Judith in the room next the Tribune,

as you return from this outer one. It is just under Lionardo's

Medusa. She is returning to the camp of her Israel, followed

by her maid carrying the head of Holofernes. And she walks in

one of Botticelli's light dancing actions, her drapery all on

flutter, and her hand, like Fortitude's, light on the

sword-hilt, but daintily—not nervously, the little finger laid

over the cross of it.

And at the first

glance—you will think the figure merely a piece of

fifteenth-century affectation. 'Judith, indeed!—say rather the

daughter of Herodias, at her mincingest.'

Well, yes—Botticelli is

affected, in the way that all men in that century necessarily

were. Much euphuism, much studied grace of manner, much formal

assertion of scholarship, mingling with his force of

imagination. And he likes twisting the fingers of hands about,

just as Correggio does. But he never does it like Correggio,

without cause.

Look at Judith again,—at

her face, not her drapery,—and remember that when a man is

base at the heart, he blights his virtues into weaknesses; but

when he is true at the heart, he sanctifies his weaknesses

into virtues. It is a weakness of Botticelli's, this love of

dancing motion and waved drapery; but why has he given it full

flight here?

Do you happen to know

anything about Judith yourself, except that she cut off

Holofernes' head; and has been made the high light of about a

million of vile pictures ever since, in which the painters

thought they could surely attract the public to the double

show of an execution, and a pretty woman,—especially with the

added pleasure of hinting at previously ignoble sin?

40. When you go home

to-day, take the pains to write out for yourself, in the

connection I here place them, the verses underneath numbered

from the book of Judith; you will probably think of their

meaning more carefully as you write.

Begin thus:

"Now at that time,

Judith heard thereof, which was the daughter of Merari, ...

the son of Simeon, the son of Israel." And then write out,

consecutively, these pieces—

Chapter viii., verses 2

to 8. (Always inclusive,) and read the whole chapter.

Chapter ix., verses 1

and 5 to 7, beginning this piece with the previous sentence,

"Oh God, oh my God, hear me also, a widow."

Chapter ix., verses 11

to 14.

Chapter x., verses 1 to 5.

Chapter xiii., verses 6 to 10.

Chapter xv., verses 11 to 13.

Chapter xvi., verses 1 to 6.

Chapter xvi., verses 11 to 15.

Chapter xvi., verses 18 and 19.

Chapter xvi., verses 23 to 25.

Now, as in many other

cases of noble history, apocryphal and other, I do not in the

least care how far the literal facts are true. The conception

of facts, and the idea of Jewish womanhood, are there, grand

and real as a marble statue,—possession for all ages. And you

will feel, after you have read this piece of history, or epic

poetry, with honourable care, that there is somewhat more to

be thought of and pictured in Judith, than painters have

mostly found it in them to show you; that she is not merely

the Jewish Delilah to the Assyrian Samson; but the mightiest,

purest, brightest type of high passion in severe womanhood

offered to our human memory. Sandro's picture is but slight;

but it is true to her, and the only one I know that is; and

after writing out these verses, you will see why he gives her

that swift, peaceful motion, while you read in her face, only

sweet solemnity of dreaming thought. "My people delivered, and

by my hand; and God has been gracious to His handmaid!" The

triumph of Miriam over a fallen host, the fire of exulting

mortal life in an immortal hour, the purity and severity of a

guardian angel—all are here; and as her servant follows,

carrying indeed the head, but invisible—(a mere thing to be

carried—no more to be so much as thought of)—she looks only at

her mistress, with intense, servile, watchful love. Faithful,

not in these days of fear only, but hitherto in all her life,

and afterwards forever.

41. After you have seen

it enough, look also for a little while at Angelico's Marriage

and Death of the Virgin, in the same room; you may afterwards

associate the three pictures always together in your mind.

And, looking at nothing else to-day in the Uffizi, let us go

back to Giotto's chapel.

We must begin with this

work on our left hand, the Death of St. Francis; for it is the

key to all the rest. Let us hear first what Mr. Crowe directs

us to think of it. "In the composition of this scene, Giotto

produced a masterpiece, which served as a model but too often

feebly imitated by his successors. Good arrangement, variety

of character and expression in the heads, unity and harmony in

the whole, make this an exceptional work of its kind. As a

composition, worthy of the fourteenth century, Ghirlandajo and

Benedetto da Majano both imitated, without being able to

improve it. No painter ever produced its equal except Raphael;

nor could a better be created except in so far as regards

improvement in the mere rendering of form."

To these inspiring

observations by the rapturous Crowe, more cautious

Cavalcasella[1] appends a refrigerating

note, saying, "The St. Francis in the glory is new, but the

angels are in part preserved. The rest has all been more or

less retouched; and no judgment can be given as to the colour

of this—or any other (!)—of these works."

You are,

therefore—instructed reader—called upon to admire a piece of

art which no painter ever produced the equal of except

Raphael; but it is unhappily deficient, according to Crowe, in

the "mere rendering of form"; and, according to Signor

Cavalcasella, "no opinion can be given as to its colour."

42. Warned thus of the

extensive places where the ice is dangerous, and forbidden to

look here either for form or colour, you are to admire "the

variety of character and expression in the heads." I do not

myself know how these are to be given without form or colour;

but there appears to me, in my innocence, to be only one head

in the whole picture, drawn up and down in different

positions.

The "unity and harmony"

of the whole—which make this an exceptional work of its

kind—mean, I suppose, its general look of having been painted

out of a scavenger's cart; and so we are reduced to the last

article of our creed according to Crowe,—

"In the composition of

this scene Giotto produced a masterpiece."

Well, possibly. The

question is, What you mean by 'composition.' Which, putting

modern criticism now out of our way, I will ask the reader to

think, in front of this wreck of Giotto, with some care.

Was it, in the first

place, to Giotto, think you, the, "composition of a scene," or

the conception of a fact? You probably, if a fashionable

person, have seen the apotheosis of Margaret in Faust? You

know what care is taken, nightly, in the composition of that

scene,—how the draperies are arranged for it; the lights

turned off, and on; the fiddlestrings taxed for their utmost

tenderness; the bassoons exhorted to a grievous solemnity.

You don't believe,

however, that any real soul of a Margaret ever appeared to any

mortal in that manner?

Here is an apotheosis also.

Composed!—yes; figures high on the right and left, low in the

middle, etc., etc., etc.

43. But the important

questions seem to me, Was there ever a St. Francis?— did

he ever receive stigmata?—didhis soul go up to

heaven—did any monk see it rising—and did Giotto mean to tell

us so? If you will be good enough to settle these few small

points in your mind first, the "composition" will take a

wholly different aspect to you, according to your answer.

Nor does it seem

doubtful to me what your answer, after investigation made,

must be.

There assuredly was a

St. Francis, whose life and works you had better study than

either to-day's Galignani, or whatever, this year, may supply

the place of the Tichborne case, in public interest.

His reception of the

stigmata is, perhaps, a marvellous instance of the power of

imagination over physical conditions; perhaps an equally

marvellous instance of the swift change of metaphor into

tradition; but assuredly, and beyond dispute, one of the most

influential, significant, and instructive traditions possessed

by the Church of Christ. And, that, if ever soul rose to

heaven from the dead body, his soul did so rise, is equally

sure.

And, finally, Giotto

believed that all he was called on to represent, concerning

St. Francis, really had taken place, just as surely as you, if

you are a Christian, believe that Christ died and rose again;

and he represents it with all fidelity and passion: but, as I

just now said, he is a man of supreme common sense;—has as

much humour and clearness of sight as Chaucer, and as much

dislike of falsehood in clergy, or in professedly pious

people: and in his gravest moments he will still see and say

truly that what is fat, is fat—and what is lean, lean—and what

is hollow, empty.

44. His great point,

however, in this fresco, is the assertion of the reality of

the stigmata against all question. There is not only one St.

Thomas to be convinced; there are five;—one to each wound. Of

these, four are intent only on satisfying their curiosity, and

are peering or probing; one only kisses the hand he has

lifted. The rest of the picture never was much more than a

grey drawing of a noble burial service; of all concerned in

which, one monk, only, is worthy to see the soul taken up to

heaven; and he is evidently just the monk whom nobody in the

convent thought anything of. (His face is all repainted; but

one can gather this much, or little, out of it, yet.)

Of the composition, or

"unity and harmony of the whole," as a burial service, we may

better judge after we have looked at the brighter picture of

St. Francis's Birth—birth spiritual, that is to say, to his

native heaven; the uppermost, namely, of the three subjects on

this side of the chapel. It is entirely characteristic of

Giotto; much of it by his hand—all of it beautiful. All

important matters to be known of Giotto you may know from this

fresco.

'But we can't see it,

even with our opera-glasses, but all foreshortened and

spoiled. What is the use of lecturing us on this?'

That is precisely the

first point which is essentially Giottesque in it; its being

so out of the way! It is this which makes it a perfect

specimen of the master. I will tell you next something about a

work of his which you can see perfectly, just behind you on

the opposite side of the wall; but that you have half to break

your neck to look at this one, is the very first thing I want

you to feel.

45. It is a

characteristic—(as far as I know, quite a universal one)—of

the greatest masters, that they never expect you to look at

them; seem always rather surprised if you want to; and not

overpleased. Tell them you are going to hang their picture at

the upper end of the table at the next great City dinner, and

that Mr. So and So will make a speech about it; you produce no

impression upon them whatever, or an unfavourable one. The

chances are ten to one they send you the most rubbishy thing

they can find in their lumber-room. But send for one of them

in a hurry, and tell him the rats have gnawed a nasty hole

behind the parlor door, and you want it plastered and painted

over;—and he does you a masterpiece which the world will peep

behind your door to look at for ever.

I have no time to tell

you why this is so; nor do I know why, altogether; but so it

is.

Giotto, then, is sent

for, to paint this high chapel: I am not sure if he chose his

own subjects from the life of St. Francis: I think so,—but of

course can't reason on the guess securely. At all events, he

would have much of his own way in the matter.

46. Now you must observe

that painting a Gothic chapel rightly is just the same thing

as painting a Greek vase rightly. The chapel is merely the

vase turned upside-down, and outside-in. The principles of

decoration are exactly the same. Your decoration is to be

proportioned to the size of your vase; to be together

delightful when you look at the cup, or chapel, as a whole; to

be various and entertaining when you turn the cup round; (you

turn yourself round in the chapel;) and to bend its

heads and necks of figures about, as it best can, over the

hollows, and ins and outs, so that anyhow, whether too long or

too short-possible or impossible—they may be living, and full

of grace. You will also please take it on my word today—in

another morning walk you shall have proof of it—that Giotto

was a pure Etruscan-Greek of the thirteenth century: converted

indeed to worship St. Francis instead of Heracles; but as far

as vase-painting goes, precisely the Etruscan he was before.

This is nothing else than a large, beautiful, coloured

Etruscan vase you have got, inverted over your heads like a

diving-bell.'[2]

Accordingly, after the

quatrefoil ornamentation of the top of the bell, you get two

spaces at the sides under arches, very difficult to cramp

one's picture into, if it is to be a picture only; but

entirely provocative of our old Etruscan instinct of ornament.

And, spurred by the difficulty, and pleased by the national

character of it, we put our best work into these arches,

utterly neglectful of the public below,—who will see the white

and red and blue spaces, at any rate, which is all they will

want to see, thinks Giotto, if he ever looks down from his

scaffold.

47. Take the highest

compartment, then, on the left, looking towards the window. It

was wholly impossible to get the arch filled with figures,

unless they stood on each other's heads; so Giotto ekes it out

with a piece of fine architecture. Raphael, in the Sposalizio,

does the same, for pleasure.

Then he puts two dainty

little white figures, bending, on each flank, to stop up his

corners. But he puts the taller inside on the right, and

outside on the left. And he puts his Greek chorus of observant

and moralizing persons on each side of his main action.

Then he puts one

Choragus—or leader of chorus, supporting the main action—on

each side. Then he puts the main action in the middle—which is

a quarrel about that white bone of contention in the centre.

Choragus on the right, who sees that the bishop is going to

have the best of it, backs him serenely. Choragus on the left,

who sees that his impetuous friend is going to get the worst

of it, is pulling him back, and trying to keep him quiet. The

subject of the picture, which, after you are quite sure it is

good as a decoration, but not till then, you may be allowed to

understand, is the following. One of St. Francis's three great

virtues being Obedience, he begins his spiritual life by

quarreling with his father. He, I suppose in modern terms I

should say, commercially invests some of his father's goods in

charity. His father objects to that investment; on which St.

Francis runs away, taking what he can find about the house

along with him. His father follows to claim his property, but

finds it is all gone, already; and that St. Francis has made

friends with the Bishop of Assisi. His father flies into an

indecent passion, and declares he will disinherit him; on

which St. Francis then and there takes all his clothes off,

throws them frantically in his father's face, and says he has

nothing more to do with clothes or father. The good Bishop, in

tears of admiration, embraces St. Francis, and covers him with

his own mantle.

48. I have read the

picture to you as, if Mr. Spurgeon knew anything about art,

Mr. Spurgeon would read it,—that is to say, from the plain,

common sense, Protestant side. If you are content with that

view of it, you may leave the chapel, and, as far as any study

of history is concerned, Florence also; for you can never know

anything either about Giotto, or her.

Yet do not be afraid of

my re-reading it to you from the mystic, nonsensical, and

Papistical side. I am going to read it to you—if after many

and many a year of thought, I am able—as Giotto meant it;

Giotto being, as far as we know, then the man of strongest

brain and hand in Florence; the best friend of the best

religious poet of the world; and widely differing, as his

friend did also, in his views of the world, from either Mr.

Spurgeon, or Pius IX.

The first duty of a

child is to obey its father and mother; as the first duty of a

citizen to obey the laws of his state. And this duty is so

strict that I believe the only limits to it are those fixed by

Isaac and Iphigenia. On the other hand, the father and mother

have also a fixed duty to the child—not to provoke it to

wrath. I have never heard this text explained to fathers and

mothers from the pulpit, which is curious. For it appears to

me that God will expect the parents to understand their duty

to their children, better even than children can be expected

to know their duty to their parents.

49. But farther. A child's

duty is to obey its parents. It is never said anywhere in the

Bible, and never was yet said in any good or wise book, that a

man's, or woman's, is. When, precisely, a child

becomes a man or a woman, it can no more be said, than when it

should first stand on its legs. But a time assuredly comes

when it should. In great states, children are always trying to

remain children, and the parents wanting to make men and women

of them. In vile states, the children are always wanting to be

men and women, and the parents to keep them children. It may

be—and happy the house in which it is so—that the father's at

least equal intellect, and older experience, may remain to the

end of his life a law to his children, not of force, but of

perfect guidance, with perfect love. Rarely it is so; not

often possible. It is as natural for the old to be prejudiced

as for the young to be presumptuous; and, in the change of

centuries, each generation has something to judge of for

itself.

But this scene, on which

Giotto has dwelt with so great force, represents, not the

child's assertion of his independence, but his adoption of

another Father.

50. You must not confuse

the desire of this boy of Assisi to obey God rather than man,

with the desire of your young cockney Hopeful to have a

latch-key, and a separate allowance.

No point of duty has

been more miserably warped and perverted by false priests, in

all churches, than this duty of the young to choose whom they

will serve. But the duty itself does not the less exist; and

if there be any truth in Christianity at all, there will come,

for all true disciples, a time when they have to take that

saying to heart, "He that loveth father or mother more than

me, is not worthy of me."

"Loveth"—observe. There is no

talk of disobeying fathers or mothers whom you do not love, or

of running away from a home where you would rather not stay.

But to leave the home which is your peace, and to be at enmity

with those who are most dear to you,—this, if there be meaning

in Christ's words, one day or other will be demanded of His

true followers.

And there is meaning in

Christ's words. Whatever misuse may have been made of

them,—whatever false prophets—and Heaven knows there have been

many—have called the young children to them, not to bless, but

to curse, the assured fact remains, that if you will obey God,

there will come a moment when the voice of man will be raised,

with all its holiest natural authority, against you. The

friend and the wise adviser—the brother and the sister—the

father and the master—the entire voice of your prudent and

keen-sighted acquaintance—the entire weight of the scornful

stupidity of the vulgar world—for once, they will be

against you, all at one. You have to obey God rather than man.

The human race, with all its wisdom and love, all its

indignation and folly, on one side,—God alone on the other.

You have to choose.

That is the meaning of

St. Francis's renouncing his inheritance; and it is the

beginning of Giotto's gospel of Works. Unless this hardest of

deeds be done first,—this inheritance of mammon and the world

cast away,—all other deeds are useless. You cannot serve,

cannot obey, God and mammon. No charities, no obediences, no

self-denials, are of any use, while you are still at heart in

conformity with the world. You go to church, because the world

goes. You keep Sunday, because your neighbours keep it. But

you dress ridiculously, because your neighbours ask it; and

you dare not do a rough piece of work, because your neighbours

despise it. You must renounce your neighbour, in his riches

and pride, and remember him in his distress. That is St.

Francis's 'disobedience.'

51. And now you can

understand the relation of subjects throughout the chapel, and

Giotto's choice of them.

The roof has the symbols

of the three virtues of labour—Poverty, Chastity, Obedience.

A. Highest on the left

side, looking to the window. The life of St. Francis begins in

his renunciation of the world.

B. Highest on the right

side. His new life is approved and ordained by the authority

of the church.

C. Central on the left

side. He preaches to his own disciples.

D. Central on the right

side. He preaches to the heathen.

E. Lowest on the left

side. His burial.

F. Lowest on the right

side. His power after death.

Besides these six

subjects, there are, on the sides of the window, the four

great Franciscan saints, St. Louis of France, St. Louis of

Toulouse, St. Clare, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary.

So that you have in the

whole series this much given you to think of: first, the law

of St. Francis's conscience; then, his own adoption of it;

then, the ratification of it by the Christian Church; then,

his preaching it in life; then, his preaching it in death; and

then, the fruits of it in his disciples.

52. I have only been

able myself to examine, or in any right sense to see, of this

code of subjects, the first, second, fourth, and the St. Louis

and Elizabeth. I will ask you only to look at two more

of them, namely, St. Francis before the Soldan, midmost on

your right, and St. Louis.

The Soldan, with an

ordinary opera-glass, you may see clearly enough; and I think

it will be first well to notice some technical points in it.

If the little virgin on

the stairs of the temple reminded you of one composition of

Titian's, this Soldan should, I think, remind you of all that

is greatest in Titian; so forcibly, indeed, that for my own

part, if I had been told that a careful early fresco by Titian

had been recovered in Santa Croce, I could have believed both

report and my own eyes, more quickly than I have been able to

admit that this is indeed by Giotto. It is so great that—had

its principles been understood-there was in reality nothing

more to be taught of art in Italy; nothing to be invented

afterwards, except Dutch effects of light.

That there is no 'effect

of light' here arrived at, I beg you at once to observe as a

most important lesson. The subject is St. Francis challenging

the Soldan's Magi,—fire-worshippers—to pass with him through

the fire, which is blazing red at his feet. It is so hot that

the two Magi on the other side of the throne shield their

faces. But it is represented simply as a red mass of writhing

forms of flame; and casts no firelight whatever. There is no

ruby colour on anybody's nose: there are no black shadows

under anybody's chin; there are no Rembrandtesque gradations

of gloom, or glitterings of sword-hilt and armour.

53. Is this ignorance,

think you, in Giotto, and pure artlessness? He was now a man

in middle life, having passed all his days in painting, and

professedly, and almost contentiously, painting things as he

saw them. Do you suppose he never saw fire cast firelight?—and

he the friend of Dante! who of all poets is the most subtle in

his sense of every kind of effect of light—though he has been

thought by the public to know that of fire only. Again and

again, his ghosts wonder that there is no shadow cast by

Dante's body; and is the poet's friend, because a

painter, likely, therefore, not to have known that mortal

substance casts shadow, and terrestrial flame, light? Nay, the

passage in the 'Purgatorio' where the shadows from the morning

sunshine make the flames redder, reaches the accuracy of

Newtonian science; and does Giotto, think you, all the while,

see nothing of the sort?

The fact was, he saw

light so intensely that he never for an instant thought of

painting it. He knew that to paint the sun was as impossible

as to stop it; and he was no trickster, trying to find out

ways of seeming to do what he did not. I can paint a

rose,—yes; and I will. I can't paint a red-hot coal; and I

won't try to, nor seem to. This was just as natural and

certain a process of thinking with him, as the honesty

of it, and true science, were impossible to the false painters

of the sixteenth century.

54. Nevertheless, what

his art can honestly do to make you feel as much as he wants

you to feel, about this fire, he will do; and that studiously.

That the fire be luminous or not, is no matter just

now. But that the fire is hot, he would have you to

know. Now, will you notice what colours he has used in the

whole picture. First, the blue background, necessary to unite

it with the other three subjects, is reduced to the smallest

possible space. St. Francis must be in grey, for that is his

dress; also the attendant of one of the Magi is in grey; but

so warm, that, if you saw it by itself, you would call it

brown. The shadow behind the throne, which Giotto knows he can

paint, and therefore does, is grey also. The rest of the

picture [3] in at least

six-sevenths of its area—is either crimson, gold, orange,

purple, or white, all as warm as Giotto could paint them; and

set off by minute spaces only of intense black,—the Soldan's

fillet at the shoulders, his eyes, beard, and the points

necessary in the golden pattern behind. And the whole picture

is one glow.

55. A single glance

round at the other subjects will convince you of the special

character in this; but you will recognize also that the four

upper subjects, in which St. Francis's life and zeal are

shown, are all in comparatively warm colours, while the two

lower ones—of the death, and the visions after it—have been

kept as definitely sad and cold.

Necessarily, you might

think, being full of monks' dresses. Not so. Was there any

need for Giotto to have put the priest at the foot of the dead

body, with the black banner stooped over it in the shape of a

grave? Might he not, had he chosen, in either fresco, have

made the celestial visions brighter? Might not St. Francis

have appeared in the centre of a celestial glory to the

dreaming Pope, or his soul been seen of the poor monk, rising

through more radiant clouds? Look, however, how radiant, in

the small space allowed out of the blue, they are in reality.

You cannot anywhere see a lovelier piece of Giottesque colour,

though here, you have to mourn over the smallness of the

piece, and its isolation. For the face of St. Francis himself

is repainted, and all the blue sky; but the clouds and four

sustaining angels are hardly retouched at all, and their

iridescent and exquisitely graceful wings are left with really

very tender and delicate care by the restorer of the sky. And

no one but Giotto or Turner could have painted them.

56. For in all his use

of opalescent and warm colour, Giotto is exactly like Turner,

as, in his swift expressional power, he is like Gainsborough.

All the other Italian religious painters work out their

expression with toil; he only can give it with a touch. All

the other great Italian colourists see only the beauty of

colour, but Giotto also its brightness. And none of the

others, except Tintoret, understood to the full its symbolic

power; but with those—Giotto and Tintoret—there is always, not

only a colour harmony, but a colour secret. It is not merely

to make the picture glow, but to remind you that St. Francis

preaches to a fire-worshipping king, that Giotto covers the

wall with purple and scarlet;—and above, in the dispute at

Assisi, the angry father is dressed in red, varying like

passion; and the robe with which his protector embraces St.

Francis, blue, symbolizing the peace of Heaven, Of course

certain conventional colours were traditionally employed by

all painters; but only Giotto and Tintoret invent a symbolism

of their own for every picture. Thus in Tintoret's picture of

the fall of the manna, the figure of God the Father is

entirely robed in white, contrary to all received custom: in

that of Moses striking the rock, it is surrounded by a

rainbow. Of Giotto's symbolism in colour at Assisi, I have

given account elsewhere.4

You are not to think,

therefore, the difference between the colour of the upper and

lower frescos unintentional. The life of St. Francis was

always full of joy and triumph. His death, in great suffering,

weariness, and extreme humility. The tradition of him reverses

that of Elijah; living, he is seen in the chariot of fire;

dying, he submits to more than the common sorrow of death.

57. There is, however,

much more than a difference in colour between the upper and

lower frescos. There is a difference in manner which I cannot

account for; and above all, a very singular difference in

skill,—indicating, it seems to me, that the two lower were

done long before the others, and afterwards united and

harmonized with them. It is of no interest to the general

reader to pursue this question; but one point he can notice

quickly, that the lower frescos depend much on a mere black or

brown outline of the features, while the faces above are

evenly and completely painted in the most accomplished

Venetian manner:—and another, respecting the management of the

draperies, contains much interest for us.

Giotto never succeeded,

to the very end of his days, in representing a figure lying

down, and at ease. It is one of the most curious points in all

his character. Just the thing which he could study from nature

without the smallest hindrance, is the thing he never can

paint; while subtleties of form and gesture, which depend

absolutely on their momentariness, and actions in which no

model can stay for an instant, he seizes with infallible

accuracy.

Not only has the

sleeping Pope, in the right hand lower fresco, his head laid

uncomfortably on his pillow, but all the clothes on him are in

awkward angles, even Giotto's instinct for lines of drapery

failing him altogether when he has to lay it on a reposing

figure. But look at the folds of the Soldan's robe over his

knees. None could be more beautiful or right; and it is to me

wholly inconceivable that the two paintings should be within

even twenty years of each other in date—the skill in the upper

one is so supremely greater. We shall find, however, more than

mere truth in its casts of drapery, if we examine them.

58. They are so simply

right, in the figure of the Soldan, that we do not think of

them;—we see him only, not his dress But we see dress first,

in the figures of the discomfited Magi. Very fully draped

personages these, indeed,—with trains, it appears, four yards

long, and bearers of them.

The one nearest the

Soldan has done his devoir as bravely as he could; would fain

go up to the fire, but cannot; is forced to shield his face,

though he has not turned back. Giotto gives him full sweeping

breadth of fold; what dignity he can;—a man faithful to his

profession, at all events.

The next one has no such

courage. Collapsed altogether, he has nothing more to say for

himself or his creed. Giotto hangs the cloak upon him, in

Ghirlandajo's fashion, as from a peg, but with ludicrous

narrowness of fold. Literally, he is a 'shut-up' Magus—closed

like a fan. He turns his head away, hopelessly. And the last

Magus shows nothing but his back, disappearing through the

door.

Opposed to them, in a

modern work, you would have had a St. Francis standing as high

as he could in his sandals, contemptuous, denunciatory;

magnificently showing the Magi the door. No such thing, says

Giotto. A somewhat mean man; disappointing enough in

presence-even in feature; I do not understand his gesture,

pointing to his forehead—perhaps meaning, 'my life, or my

head, upon the truth of this.' The attendant monk behind him

is terror-struck; but will follow his master. The dark Moorish

servants of the Magi show no emotion—will arrange their

masters' trains as usual, and decorously sustain their

retreat.

59. Lastly, for the

Soldan himself. In a modern work, you would assuredly have had

him staring at St. Francis with his eyebrows up, or frowning

thunderously at his Magi, with them bent as far down as they

would go. Neither of these aspects does he bear, according to

Giotto. A perfect gentleman and king, he looks on his Magi

with quiet eyes of decision; he is much the noblest person in

the room—though an infidel, the true hero of the scene, far

more than St. Francis. It is evidently the Soldan whom Giotto

wants you to think of mainly, in this picture of Christian

missionary work.

He does not altogether

take the view of the Heathen which you would get in an Exeter

Hall meeting. Does not expatiate on their ignorance, their

blackness, or their nakedness. Does not at all think of the

Florentine Islington and Pentonville, as inhabited by persons

in every respect superior to the kings of the East; nor does

he imagine every other religion but his own to be log-worship.

Probably the people who really worship logs—whether in Persia

or Pentonville—will be left to worship logs to their hearts'

content, thinks Giotto. But to those who worship God,

and who have obeyed the laws of heaven written in their

hearts, and numbered the stars of it visible to them,—to

these, a nearer star may rise; and a higher God be revealed.

You are to note,

therefore, that Giotto's Soldan is the type of all noblest

religion and law, in countries where the name of Christ has

not been preached. There was no doubt what king or people

should be chosen: the country of the three Magi had already

been indicated by the miracle of Bethlehem; and the religion

and morality of Zoroaster were the purest, and in spirit the

oldest, in the heathen world. Therefore, when Dante, in the

nineteenth and twentieth books of the Paradise, gives his

final interpretation of the law of human and divine justice in

relation to the gospel of Christ—the lower and enslaved body

of the heathen being represented by St. Philip's convert,

("Christians like these the Ethiop shall condemn")—the noblest

state of heathenism is at once chosen, as by Giotto: "What may

the Persians say unto your kings?" Compare

also Milton,—

"At

the

Soldan's chair,

Defied

the

best of Paynim chivalry."

60. And now, the time is

come for you to look at Giotto's St. Louis, who is the type of

a Christian king.

You would, I suppose,

never have seen it at all, unless I had dragged you here on

purpose. It was enough in the dark originally—is trebly

darkened by the modern painted glass—and dismissed to its

oblivion contentedly by Mr. Murray's "Four saints, all much

restored and repainted," and Messrs. Crowe and Cavalcasella's

serene "The St. Louis is quite new."

Now, I am the last

person to call any restoration whatever, judicious. Of all

destructive manias, that of restoration is the frightfullest

and foolishest. Nevertheless, what good, in its miserable way,

it can bring, the poor art scholar must now apply his common

sense to take; there is no use, because a great work has been

restored, in now passing it by altogether, not even looking

for what instruction we still may find in its design, which

will be more intelligible, if the restorer has had any

conscience at all, to the ordinary spectator, than it would

have been in the faded work. When, indeed, Mr. Murray's Guide

tells you that a building has been 'magnificently

restored,' you may pass the building by in resigned despair;

for that means that every bit of the old sculpture has

been destroyed, and modern vulgar copies put up in its place.

But a restored picture or fresco will often be, to you,

more useful than a pure one; and in all probability—if an

important piece of art—it will have been spared in many

places, cautiously completed in others, and still assert

itself in a mysterious way—as Leonardo's Cenacolo does—through

every phase of reproduction. [5]

61. But I can assure

you, in the first place, that St. Louis is by no means

altogether new. I have been up at it, and found most lovely

and true colour left in many parts: the crown, which you will

find, after our mornings at the Spanish chapel, is of

importance, nearly untouched; the lines of the features and

hair, though all more or less reproduced, still of definite

and notable character; and the junction throughout of added

colour so careful, that the harmony of the whole, if not

delicate with its old tenderness, is at least, in its coarser

way, solemn and unbroken. Such as the figure remains, it still

possesses extreme beauty—profoundest interest. And, as you can

see it from below with your glass, it leaves little to be

desired, and may be dwelt upon with more profit than nine out

of ten of the renowned pictures of the Tribune or the Pitti.

You will enter into the spirit of it better if I first

translate for you a little piece from the Fioretti di San

Francesco.

62. "How St. Louis, King

of France, went personally in the guise of a pilgrim, to

Perugia, to visit the holy Brother Giles.—St. Louis, King of

France, went on pilgrimage to visit the sanctuaries of the

world; and hearing the most great fame of the holiness of

Brother Giles, who had been among the first companions of St.

Francis, put it in his heart, and determined assuredly that he

would visit him personally; wherefore he came to Perugia,

where was then staying the said brother. And coming to the

gate of the place of the Brothers, with few companions, and

being unknown, he asked with great earnestness for Brother

Giles, telling nothing to the porter who he was that asked.

The porter, therefore, goes to Brother Giles, and says that

there is a pilgrim asking for him at the gate. And by God it

was inspired in him and revealed that it was the King of

France; whereupon quickly with great fervour he left his cell

and ran to the gate, and without any question asked, or ever

having seen each other before, kneeling down together with

greatest devotion, they embraced and kissed each other with as

much familiarity as if for a long time they had held great

friendship; but all the while neither the one nor the other

spoke, but stayed, so embraced, with such signs of charitable

love, in silence. And so having remained for a great while,

they parted from one another, and St. Louis went on his way,

and Brother Giles returned to his cell. And the King being

gone, one of the brethren asked of his companion who he was,

who answered that he was the King of France. Of which the

other brothers being told, were in the greatest melancholy

because Brother Giles had never said a word to him; and

murmuring at it, they said, 'Oh, Brother Giles, wherefore

hadst thou so country manners that to so holy a king, who had

come from France to see thee and hear from thee some good

word, thou hast spoken nothing?'

"Answered Brother Giles:

'Dearest brothers, wonder not ye at this, that neither I to

him, nor he to me, could speak a word; for so soon as we had

embraced, the light of the divine wisdom revealed and

manifested, to me, his heart, and to him, mine; and so by

divine operation we looked each in the other's heart on what

we would have said to one another, and knew it better far than

if we had spoken with the mouth, and with more consolation,

because of the defect of the human tongue, which cannot

clearly express the secrets of God, and would have been for

discomfort rather than comfort. And know, therefore, that the

King parted from me marvellously content, and comforted in his

mind.'"

63. Of all which story,

not a word, of course, is credible by any rational person.

Certainly not: the

spirit, nevertheless, which created the story, is an entirely

indisputable fact in the history of Italy and of mankind.

Whether St. Louis and Brother Giles ever knelt together in the

street of Perugia matters not a whit. That a king and a poor

monk could be conceived to have thoughts of each other which

no words could speak; and that indeed the King's tenderness

and humility made such a tale credible to the people,—this is

what you have to meditate on here.

Nor is there any better

spot in the world,—whencesoever your pilgrim feet may have

journeyed to it, wherein to make up so much mind as you have

in you for the making, concerning the nature of Kinghood and

Princedom generally; and of the forgeries and mockeries of

both which are too often manifested in their room. For it

happens that this Christian and this Persian King are better

painted here by Giotto than elsewhere by any one, so as to

give you the best attainable conception of the Christian and

Heathen powers which have both received, in the book which

Christians profess to reverence, the same epithet as the King

of the Jews Himself; anointed, or Christos:—and as the most

perfect Christian Kinghood was exhibited in the life, partly

real, partly traditional, of St. Louis, so the most perfect

Heathen Kinghood was exemplified in the life, partly real,

partly traditional, of Cyrus of Persia, and in the laws for

human government and education which had chief force in his

dynasty. And before the images of these two Kings I think

therefore it will be well that you should read the charge to

Cyrus, written by Isaiah. The second clause of it, if not all,

will here become memorable to you—literally illustrating, as

it does, the very manner of the defeat of the Zoroastrian

Magi, on which Giotto founds his Triumph of Faith. I write the

leading sentences continuously; what I omit is only their

amplification, which you can easily refer to at home. (Isaiah

xliv. 24, to xlv. 13.)

64. "Thus saith the

Lord, thy Redeemer, and he that formed thee from the womb. I

the Lord that maketh all; that stretcheth forth the heavens,

alone; that spreadeth abroad the earth, alone; that

turneth wise men backward, and maketh their knowledge,

foolish; that confirmeth the word of his Servant, and

fulfilleth the counsel of his messengers: that saith of

Cyrus, He is my Shepherd, and shall perform all my pleasure,

even saying to Jerusalem, 'thou shalt be built,' and to the

temple, 'thy foundations shall be laid."

"Thus saith the Lord to

his Christ;—to Cyrus, whose right hand I have holden, to

subdue nations before him, and I will loose the loins of

Kings.

"I will go before thee,

and make the crooked places straight; I will break in pieces

the gates of brass, and cut in sunder the bars of iron; and I

will give thee the treasures of darkness, and hidden

riches of secret places, that thou mayest know that I the

Lord, which call thee by thy name, am the God of Israel.

"For Jacob my servant's

sake, and Israel mine elect, I have even called thee by thy

name; I have surnamed thee, though thou hast not known me.

"I am the Lord, and

there is none else; there is no God beside me. I girded thee,

though thou hast not known me. That they may know, from the rising

of the sun, and from the west, that there is none beside

me; I am the Lord and there is none else. I form the light,

and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil. I the Lord

do all these things.

"I have raised him up in

Righteousness, and will direct all his ways; he shall build my

city, and let go my captives, not for price nor reward, saith

the Lord of Nations."

65. To this last verse,

add the ordinance of Cyrus in fulfilling it, that you may

understand what is meant by a King's being "raised up in

Righteousness," and notice, with respect to the picture under

which you stand, the Persian King's thought of the Jewish

temple.

"In the first year of

the reign of Cyrus,[6] King Cyrus commanded

that the house of the Lord at Jerusalem should be built again,

where they do service with perpetual fire; (the

italicized sentence is Darius's, quoting Cyrus's decree—the

decree itself worded thus), Thus saith Cyrus, King of Persia:

[7] The Lord God of heaven

hath given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he hath

charged me to build him an house at Jerusalem.

"Who is there among you

of all his people?—his God be with him, and let him go up to

Jerusalem which is in Judah, and let the men of his place help

him with silver and with gold, and with goods and with

beasts."

Between which "bringing

the prisoners out of captivity" and modern liberty, free

trade, and anti-slavery eloquence, there is no small interval.

66. To these two ideals

of Kinghood, then, the boy has reached, since the day he was

drawing the lamb on the stone, as Cimabue passed by. You will

not find two other such, that I know of, in the west of

Europe; and yet there has been many a try at the painting of

crowned heads,—and King George III and Queen Charlotte, by Sir

Joshua Reynolds, are very fine, no doubt. Also your

black-muzzled kings of Velasquez, and Vandyke's long-haired

and white-handed ones; and Rubens' riders—in those handsome

boots. Pass such shadows of them as you can summon, rapidly

before your memory—then look at this St. Louis.

His face—gentle,

resolute, glacial-pure, thin-cheeked; so sharp at the chin

that the entire head is almost of the form of a knight's

shield—the hair short on the forehead, falling on each side in

the old Greek-Etruscan curves of simplest line, to the neck; I

don't know if you can see without being nearer, the difference

in the arrangement of it on the two sides-the mass of it on

the right shoulder bending inwards, while that on the left

falls straight. It is one of the pretty changes which a modern

workman would never dream of—and which assures me the restorer

has followed the old lines rightly.

He wears a crown formed

by an hexagonal pyramid, beaded with pearls on the edges: and

walled round, above the brow, with a vertical

fortress-parapet, as it were, rising into sharp pointed spines

at the angles: it is chasing of gold with pearl—beautiful in

the remaining work of it; the Soldan wears a crown of the same

general form; the hexagonal outline signifying all order,

strength, and royal economy. We shall see farther symbolism of

this kind, soon, by Simon Memmi, in the Spanish chapel.

67. I cannot tell you

anything definite of the two other frescos—for I can only

examine one or two pictures in a day; and never begin with one

till I have done with another; and I had to leave Florence

without looking at these—even so far as to be quite sure of

their subjects. The central one on the left is either the

twelfth subject of Assisi—St. Francis in Ecstacy;[8] or the eighteenth, the

Apparition of St. Francis at Arles;[9] while the lowest on the

right may admit choice between two subjects in each half of

it: my own reading of them would be—that they are the

twenty-first and twenty-fifth subjects of Assisi, the Dying

Friar[10] and Vision of Pope

Gregory IX.;[11] but Crowe and

Cavalcasella may be right in their different interpretation;[12] in any case, the

meaning of the entire system of work remains unchanged, as I

have given it above.

Notes

1· · I

venture to attribute the wiser note to Signor Cavalcasella

because I have every reason to put real confidence in his

judgment. But it was impossible for any man, engaged as he is,

to go over all the ground covered by so extensive a piece of

critical work as these three volumes contain, with effective

attention.

2· · I

observe that recent criticism is engaged in proving all

Etruscan vases to be of late manufacture, in imitation of

archaic Greek. And I therefore must briefly anticipate a

statement which I shall have to enforce in following letters.

Etruscan art remains in its own Italian valleys, of the Arno

and upper Tiber, in one unbroken series of work, from the

seventh century before Christ, to this hour, when the country

whitewasher still scratches his plaster in Etruscan patterns.

All Florentine work of the finest kind—Luca della Robbia's,

Ghiberti's, Donatello's, Filippo Lippi's, Botticelli's, Fra

Angelico's—is absolutely pure Etruscan, merely changing its

subjects, and representing the Virgin instead of Athena, and

Christ instead of Jupiter. Every line of the Florentine chisel

in the fifteenth century is based on national principles of

art which existed in the seventh century before Christ; and

Angelico, in his convent of St. Dominic, at the foot of the

hill of Fésole, is as true an Etruscan as the builder who laid

the rude stones of the wall along its crest—of which modern

civilization has used the only arch that remained for cheap

building stone. Luckily, I sketched it in 1845. but alas, too

carelessly,—never conceiving of the brutalities of modern

Italy as possible.

3· · The

floor

has been repainted; but though its grey is now heavy and cold,

it cannot kill the splendour of the rest.

4· · 'Fors

Clavigera'

for September, 1874.

5· · For

a test of your feeling in the matter, having looked well at

these two lower frescos in this chapel, walk round into the

next, and examine the lower one on your left hand as you enter

that. You will find in your Murray that the frescos in this

chapel "were also till lately, (1862) covered with whitewash";

but I happen to have a long critique of this particular

picture written in the year 1845, and I see no change in it

since then. Mr. Murray's critic also tells you to observe in

it that "the daughter of Herodias playing on a violin is not

unlike Perugino's treatment of similar subjects." By which Mr.

Murray's critic means that the male musician playing on a

violin, whom, without looking either at his dress, or at the

rest of the fresco, he took for the daughter of Herodias, has

a broad face. Allowing you the full benefit of this

criticism—there is still a point or two more to be observed.

This is the only fresco near the ground in which Giotto's work

is untouched, at least, by the modern restorer. So

felicitously safe it is, that you may learn from it at once

and for ever, what good fresco painting is—how quiet—how

delicately clear—how little coarsely or vulgarly

attractive—how capable of the most tender light and shade, and

of the most exquisite and enduring colour. In this latter

respect, this fresco stands almost alone among the works of

Giotto; the striped curtain behind the table being wrought

with a variety and fantasy of playing colour which Paul

Veronese could not better at his best. You will find, without

difficulty, in spite of the faint tints, the daughter of

Herodias in the middle of the picture—-slowly moving,

not dancing, to the violin music—she herself playing on a

lyre. In the farther corner of the picture, she gives St.

John's head to her mother; the face of Herodias is almost

entirely faded, which may be a farther guarantee to you of the

safety of the rest. The subject of the Apocalypse, highest on

the right, is one of the most interesting mythic pictures in

Florence; nor do I know any other so completely rendering the

meaning of the scene between the woman in the wilderness, and

the Dragon enemy. But it cannot be seen from the floor level:

and I have no power of showing its beauty in words.

6· · 1st

Esdras

vi. 24.

7· · Ezra

i. 3, and 2nd Esdras ii. 3.

8· · "Represented"

(next to St. Francis before the Soldan, at Assisi) "as seen

one night by the brethren, praying, elevated from the ground,

his hands extended like the cross, and surrounded by a shining

cloud."—Lord Lindsay.

9· · "St.

Anthony of Padua was preaching at a general chapter of the

order, held at Arles, in 1224, when St. Francis appeared in

the midst, his arms extended, and in an attitude of

benediction."—Lord Lindsay.

10· · "A

brother

of the order, lying on his deathbed, saw the spirit of St.

Francis rising to heaven, and springing forward, cried,

'Tarry, Father, I come with thee!' and fell back dead."—Lord

Lindsay.

11· · "He

hesitated,

before canonizing St. Francis; doubting the celestial

infliction of the stigmata. St. Francis appeared to him in a

vision, and with a severe countenance reproving his unbelief,

opened his robe, and, exposing the wound in his side, filled a

vial with the blood that flowed from it, and gave it to the

Pope, who awoke and found it in his hand."—Lord Lindsay.

12·

"As St. Francis was carried on his bed of sickness to

St. Maria degli Angeli, he stopped at an hospital on the

roadside, and ordering his attendants to turn his head in the

direction of Assisi, he rose in his litter and said, 'Blessed

be thou amongst cities! may the blessing of God cling to thee,

oh holy place, for by thee shall many souls be saved;' and,

having said this, he lay down and was carried on to St. Maria

degli Angeli. On the evening of the 4th of October his death

was revealed at the very hour to the bishop of Assisi on Mount

Sarzana."—Crowe

and Cavalcasella.

GO TO FOURTH MORNING

FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII,

VIII,

IX,

X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA