LA CITTA` E IL

LIBRO III

ELOQUENZA

SILENZIOSA:

VOCI DEL

RICORDO INCISE NEL

CIMITERO

'DEGLI INGLESI',

CONVEGNO

INTERNAZIONALE

3-5 GIUGNO

2004

THE CITY AND THE BOOK III

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

'MARBLE SILENCE, WORDS ON

STONE:

FLORENCE'S' ENGLISH CEMETERY',

GABINETTO VIEUSSEUX AND

'ENGLISH CEMETERY', FLORENCE

3-5 JUNE 2004

I ‘FIORENTINI’ INGLESI E AMERICANI/ ENGLISH AND AMERICAN ‘FLORENTINES’

‘‘La tentazione di Eva: Paradise Lost nella scultura di Hiram Powers: ‘Eve Tempted’ Paradise Lost in Hiram Powers' sculpture Katerine Gaja, The British Institute of Florence ||L’iscrizione sulla tomba di Walter Savage Landor/ The inscription on Walter Savage Landor's Tomb Mark Roberts, The British Institute of Florence ||La vedova di Arnold Savage Landor: Libri, corpi e l'incisione di memoria in Firenze/ Arnold Savage Landor’s Widow: Books, Bodies and Imprinting Memory in Florence Allison Levy, Wheaton College ||Fanny Trollope, la sua famiglia e la cerchia del Villino Trollope/ Fanny Trollope, her Family and Circle at the Villino Trollope David R. Gilbert, The Middle Temple, London ||Elizabeth Barrett Browning e la Bibbia/ Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Bible Stephen Prickett, The Armstrong Browning Library, Baylor University ||La pietra e la parola: Elizabeth Barrett Browning a Firenze/ Stone and Word: Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Florence Claudia Vitale

CENA presso il CIMITERO 'DEGLI INGLESI'/DINNER in the 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY, Piazzale Donatello 38

Ringraziamo

AGENZIA PER IL TURISMO

FIRENZE

AGENZIA PER IL TURISMO

FIRENZE

EVE TEMPTED: PARADISE LOST IN THE SCULPTURE OF HIRAM POWERS

KATERINE GAJA

*°§ HIRAM POWERS/ AMERICA / Powers/ Franco [later corrected to Hiram]/ Stefano/ America/ Firenze/ 27 Giugno/ 1873/ Anni 69/ 1220/ F. Hiram Powers, America, Sculpteur, fils de Etienne Powers/ HIRAM POWERS/ DIED JUNE 27TH 1873/ AGED 68/E15D °=Niccolò, Alessio Michahelles, descendants

Can it be sin to know?

Can it be death?Paradise Lost IV-517-518

Powers settled with his family in an area of sculptors' studios and remained in Florence for the rest of his life. His home and studio became a focal point for the Anglo-American community, so that his vast correspondence gives us valuable insights into a city and a society that underwent profound changes during his life-time. In many ways he acted as unofficial consul, an aspect of his career that is given due weight in Clara Dentler's unpublished biography, and in this role one of his duties was to answer queries from relatives of Americans who had died in Florence. "A more beautiful spot could hardly be found," he wrote of the cemetery at Porta al Pinti; "It is against the outer wall of the city & it looks more like a beautiful garden than a place of the dead. But tell Mrs. Woodall that all this is nothing, for her dear husband is not there now, nor are my children there. Earth has received her own but the soul is not here." (1)

ALLEN FRANCIS WOODALL/ AMERICA/

Woodall/ Allen F. / / America/ Firenze/ 12 Agosto/ 1864/ Anni

37/ 876/ Allen F. Woodall, Lexington, Amerique

* NORMA (PIERUCCI) WOODALL AND

SON/ ITALIA/KENTUCKY/ Woodall nei [nata] Pierucci/ Norma/ /

America/ 29 Settembre/ 1864/ Anni 22/ 880/ Norma Pierucci née

Woodwall, l'Amerique/ WIFE AND SON/ OF/ FRANCIS WOODALL/

BORN IN KENTUCKY, U.S.A./ DIED IN FLORENCE/ AUGUST 12 1865/

B19O

*°§ FLORENCE POWERS/ AMERICA/ Powers/ Firenze/ Hiram/ America/ Firenze/ 30 Luglio/ 1863/ Anni 17/ 840/ Florence Povers, l'Amérique, fille de Hiram Povers et de Elisabeth/ G23777/1 N° 331, Burial 01/08, Rev Pendleton/ FLORENCE// *° FRANCES AUGUSTINA POWERS/ AMERICA/ Powers/ Francesca Agostina/ Hiram/ America/ Firenze/ 29 Luglio/ 1857/ Anni 8/ 842/ Françoise Povers, l'Amérique, fille de Hiram Povers et de Elisabeth/ G23777/1 N° 332, Burial 03/08/63, Rev Pendleton/ body embalmed to send to America, then retained in Florence/ FRANCES// *° JAMES GIBSON POWERS/ AMERICA / Powers/ Giacomo Gibson/ Hiram/ America/ Firenze/ 4 Marzo/ 1838/ Anni 5/ 841/ James Gibson Povers, l'Amerique, fil de Hiram Povers et de Elisabeth/ G23777/1 N°333, Burial 03/08/63, Rev. Pendleton/ body embalmed to send to America, then retained in Florence/ JAMES// CHILDREN OF ELIZABETH AND HIRAM POWERS A11P(152)

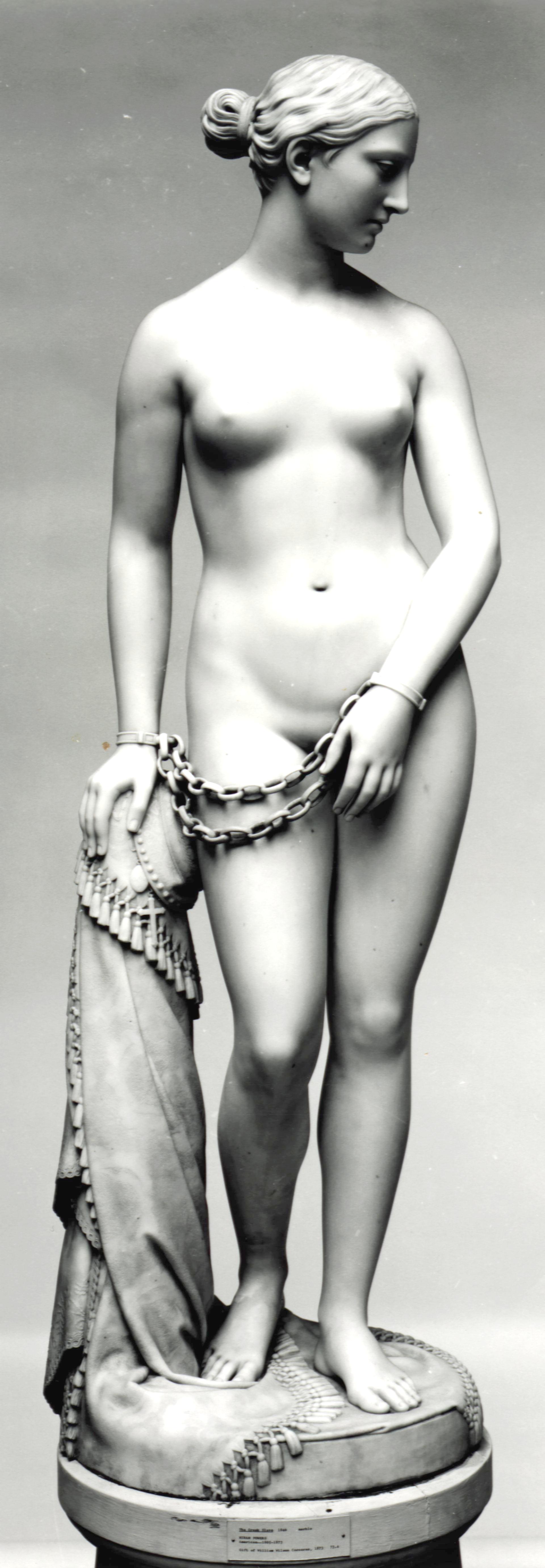

Although it was the extraordinary success of the statue The Greek Slave (1843) that brought Powers international fame, I shall focuss on his first ideal statue, Eve Tempted (1839-1842), because it originated in a commission for a tomb sculpture and because throughout its complex history it was associated with death and mourning. The five variations on the theme, spanning Powers's entire career, linked up with other writers' interpretations of a subject that had acquired immediacy since the Genesis account of creation had been called into question by new discoveries in geology. John Milton and Salomon Gessner are acknowledged literary sources for at least two versions of the statue, while Swedenborg's interpretation of the Book of Genesis was certainly familiar to Powers. Elizabeth Barrett Browning had recently published A Drama of Exile on the same theme when she first saw the plaster model of Eve Tempted in Powers's studio in 1847, and Henry Tuckerman, who corresponded with Powers, linked this work with Powers's statue of Eve Disconsolate in his Book of the Artists. (2) Robert Browning's Bishop Blougram's Apology gives an account of the erosion of unquestioning faith in the Biblical account of the origin of man, with specific references to geology and the Book of Genesis. (3)

In 1839 Powers's earliest patron, Nicholas Longworth, who had financed his journey to Italy in 1837, asked whether Powers would undertake the design of a monument for his parents in a cemetery in Newark, New Jersey. Powers wrote to Longworth on April 22 1839: "I shall begin a statue of a female figure in a few days. I think it will be an illustration of Gessner's Eve at the moment when she is looking at a dove, which lies dead at her feet and which calls up disagreeable reflections in her mind on the consequence of her trangression. I think I shall call it Eve, Reflecting on Death." (4) Gessner's popular verse drama The Death of Abel was a continuation of the story of Adam and Eve from the point where it ended in Book XII of Milton's Paradise Lost. Eve's first encounter with death is related by Adam with utmost poignancy and a realism that suggests the scientific observation of the anatomy laboratory. "It will not wake! said she to me, in a fearful voice, laying the bird from her trembling hand. - It will not wake! - It will never wake more! She then burst into tears, ...How stiff and cold it is! It has neither voice nor motion: its joints no longer bend: its limbs refuse their office. Speak, ADAM, is this death? Ah! it is. - How I tremble! An icy cold runs thro' my bones. If the death with which we are threaten'd is like this, how terrible!" (5)

The Eve inspired by Gessner, however, never got beyond the stage of a small plaster model, now lost, for when a letter to a friend describing his idea for a statue of Eve, Reflecting on Death was published in the Cincinnati Republican, (6) Powers recoiled from this unwanted and premature publicity, and rejected his original idea altogether.

***

Instead, between 1839 and 1842, he created two versions of the statue Eve Tempted. In the first version Eve holds out the forbidden fruit in her right hand, while in the second, revised version, her right hand holds the apple close to her breast. Her hair is dishevelled, and in both versions a serpent, modelled with the utmost realism from an American rattle-snake, encircles Eve's feet. As Powers wrote to John Preston, another patron, in May 1840, the serpent is "a real serpent and not a monster." (7) He also drew attention to Eve's "broad and large" feet and "long toes". (8) Both the statue itself, with the 'short and heavy' legs that suggest a common model with Bartolini's Nymph with a Serpent, (9) and Powers's description of it, linking the waves of Eve's hair with the undulations of the snake, (10) reveal a naturalism that several observers found disconcerting.

It was clearly no longer suitable for a tomb

sculpture, and in 1842 Longworth proposed a public

subscription to raise the money to commission a marble version

of Eve Tempted for the Cincinnati Art Museum. However,

public distaste for nude sculpture made the enterprise fail,

and when the ship transporting the statue to America sank off

the coast of Spain in 1850, Powers reflected in his letters

with bitter humour on the Puritanism of the American public

and the absence of a sense of shame in Eve. (11) The statue

was rescued and delivered to Preston's home in Columbia, South

Carolina, where it was locked up for years, unseen and unknown

to the public in general. This second, revised Eve Tempted, in

Seravezza marble, which Powers believed to be his best work,

(12) virtually disappeared, and is still today unlocated.

***

It was this version of Eve Tempted that Elizabeth Barrett Browning saw, in plaster, when she first visited Powers's studio in May 1847, and although it is unlikely that she knew that Eve Tempted had originally been conceived as a tomb sculpture, her interpretation of the statue is in this key. Her Sonnet on Grief compared grief to "a monumental statue set/In everlasting watch and moveless woe"; (13) only superficial mourning found an outlet in shrieking and reproaching. For her, it was a kind of integrity, not to falsify or console in words.

She thus correctly perceived the sadness that was inherent in Powers's original conception of Eve, writing to Arabel of the "Greek Slave & Fisher Boy, & the Eve yet unworked in the marble....of which I liked the Eve best...the sadness rather than the impurity of sin is in her face...just one touch of sadness - the foreshadow of all loss...It is very serene, beautifully sad - the passion is behind a cloud, as it ought always to be in sculpture -". (14)

While The Greek Slave claimed most attention in the public rhetoric of her sonnet Hiram Powers's Greek Slave, significantly, in her letters to her sister Arabel, it was Eve Tempted that interested her most. In the Preface to her verse drama on the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, A Drama of Exile (1844), she had justified her temerity in writing on the theme of Milton's Paradise Lost by saying that Eve's grief had been "imperfectly apprehended hitherto, and more expressible by a woman than a man". (15)

***

Paradoxically it was this very grief that got Powers's Eve Tempted into theological trouble. According to the American artist William J. Hubard, who saw the statue early in 1839, the sadness she perceived was not theologically correct; she showed too much intellect; she was too independent. "Your idea" - he wrote to Powers - "made Eve appear a heroine as we know these, not as a primitive and sympathetic being created to soothe and partake of man's affections. She was not a rival or equal to his mind, but an accessory to his happiness. Therefore she appears a being of more feeling than mind. In fact, intellect was developed only after she had sinned and knew good from evil." (16)

The expression could bear traces of Powers's original idea, derived from Gessner, of representing Eve at the moment when she realised the significance of death. But the independence of mind is also found in Milton's Eve: it is Eve's wish to work on her own in the garden of Eden, to be independent or, as Milton puts it, temporarily unpropped, that allows the serpent to approach and persuade her so subtly. (17) Nor is it fanciful to assume that Powers was familiar with Milton; Everett assumed so when suggesting the subject of La Penserosa to him, and so did Nathaniel Hawthorne when he claimed that the composition of La Penserosa was derived from an engraving "prefixed to a cheap American edition of Milton's poems, & was probably as familiar to Powers as to myself". (18) Powers's representation of both Eve's "dishevell'd" hair and the "circling spires" of the serpent recall Milton's poem. (19) Finally, his use of the words Paradise Lost as the first title for his statue Eve Disconsolate also suggests that Milton's work was a familiar source. We know that Powers owned a copy of John Flaxman's Lectures on Sculpture, in which the Lecture on Modern Sculpture recommends "biblical subjects and Milton's Paradise Lost". (20) Horatio Greenough followed his advice and sculpted an Abdiel, the loyal seraph from Book V of Paradise Lost, in 1838 and a Lucifer in 1841.

***

As though taking Hubard's criticisms into account, between 1858 and 1861 Powers worked on the statue known as Repentant Eve, Paradise Lost, Eve After the Fall, or Eve Disconsolate. Eve's hair is loosely bound, her finger points to the serpent slithering downwards, upside down, and her face shows bewilderment, distress and remorse; "she seems as walking in painful meditation." Powers wrote; "Her head is raised - as in supplication for foregiveness". (21) This statue was conceived as a tribute to Nicholas Longworth, and after his death in 1863 it was given to the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Thus, considering that Powers saw La Penserosa as a prototype of Eve Disconsolate (22) and that he also began a model of a statue group, Adam and Eve, in February 1861, and was working on a marble replica of the first Eve Tempted when he died, the Eve-theme was one that interested him throughout his career. The alterations he made in his statues of Eve reveal his sensitive response to criticism, as well as the tension between idealism and naturalism. Rosina Bulwer Lytton complained that in the first version of Eve Tempted 'the ideal' was missing (23), while Lady Stamer praised the sculptor for giving us "not an ideal poetical Eve...not Milton's Eve, but the living Eve of the Bible." (24) Mindful of criticism that there was no 'ideal', 'soul' or 'mind' in the first version of Eve Tempted, Powers wrote stressing just those qualities in the second version: "When I say there is more mind in it, you will understand what I mean. It makes the original look heavy and sleepy." (25) And, as we have seen, he put submission in the face of Eve Disconsolate in response to Hubard's strictures.

***

Powers spoke of his statues as though they were alive, and had a life in time. He also ventriloquised his creations, so that they uttered their thoughts; America voiced the creed of liberty and La Penserosa her misgivings about the sculptor's talents. The verbal re-casting of a statue might be at odds with the solemnity of the original, as in the sculptor's remarks about original sin and Eve's lack of a sense of shame. Powers stressed the simplicity and innocence of his Eves: "She wears her hair in a natural and most primitive manner..." (26) he wrote of Eve Tempted, speaking, again, as if the statue were alive. "She has never been in society, nor is she educated," he boasted of his Eve Disconsolate, (27) and we can understand the appeal of the Eve theme to a man who had, according to Thomas Adolphus Trollope, "a sort of original, blank-paper mind," who was "a sort of Adam, a fresh, new and original man..." (28) Sophia Hawthorne used the word 'primal' when she saw Eve Tempted in Powers's studio in 1857. (29)

Powers detested the artificiality of fashion and society. He had clear ideas of what constituted Satan: Satan was the fashion for bustles and crinolines; Satan was elaborate hair arrangements, waltzes and polkas; "The serpent who beguiled Eve has never been discharged," he wrote to a friend in 1857; "...he has distorted the human form divine - His own form is monstrous, & therefore he cannot appear in the simple garb of nature - ...I trust you will perceive how superior simplicity is to all his devices." (30) While this version of Satan might not seem to constitute a serious form of evil, it ran counter to a concept that was sacred to Powers: 'the human form divine', or Swedenborg's doctrine of 'the spiritual body'. This lay at the heart of his ideas on sculpture. The white marble statue was the embodiment of spirit, or the "unveiled soul", as he wrote to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. (31)

Studio visitors also rushed in to supply the absent verbal dimension for a statue, often in the form of poetry. (32) In the poem he dedicated to Eve Tempted, the young Bayard Taylor declared: "The daring of the sculptor's hand has wrought/A soul in that sweet face!", and Powers gratefully acknowledged the non-material dimension: "'Mind remains while matter perishes' and the poem will stand long after the statue has returned in fragments to the earth from which it was taken." (33)

There is a certain anxious insistence on the word soul in the recorded impressions of visitors to the sculptor's studio: a statue did or did not have 'soul'. Marble had a soul, according to the sculptor Thomas Ball, who imagined the plain marble of Powers's tomb in the cimitero degli inglesi voicing its gratitude for being "Raised ..from earth" and given a "soul" in his sculpture. (34)

In their different ways, Powers's five versions of Eve all bear traces of his original concept of a meditation on death, his projected group statue of Adam and Eve (1861) suggesting that the theme of the Fall of Man continued to hold his interest. Swedenborg's interpretation of the Book of Genesis (35) would have made him aware, too, of the more troubling elements in the Christian doctrine of the Fall, which taught that death and the hereditary stain of sin were the direct consequence of Eve's disobedience in eating of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. It would be understandable to query the harshness of a punishment for a natural thirst for knowledge and experience, or the value of a prolonged state of innocence, as the seraph Zerah did in Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem The Seraphim. (36) The documented literary source for Powers's first concept of Eve, Gessner's The Death of Abel, related the discovery of death in a context that made it appear not as inevitable and natural, but as a punishment for disobedience.

In his sculpture Powers counteracted the incontrovertible evidence of physical death, as so movingly portrayed in Gessner's poem, with the idea of the spiritual body, as did Gessner in describing the formation of "an etherial body" that "environ'd" the soul of Abel after his death. (37)

The idea of resurrection was implicit in the very process of sculpture, its three stages of clay, plaster and marble being traditionally compared to life, death and resurrection. According to Dentler, this was actually quoted by Thorvaldsen when he visited Powers's studio in 1841 and altered the clay of Eve's hair. (38) And so it was that Powers could write quite naturally - and humourously - in an account that also evokes the Neoplatonic idea of the soul or form being contained, hidden, in the stone, waiting to be released by the sculptor, of raising his Eve to life from the rock-face of marble at Seravezza. (39)

NOTES

(1) HP to Rev. C. George Currie, 1 September 1864

(Dentler typescript, p.126). I am grateful to Jeffey Begeal

for allowing me to quote from his transcription of Clara

Dentler's unpublished work White Marble: The Life and

Letters of Hiram Powers, Sculptor in the Smithsonian

Institution, Washington, D.C.

(2) Henry Tuckerman, Book of

the Artists. American Artist Life, New York, Putnam,

1867, p.287.

(3) "How you'd exult if I could

put you back/ Six hundred years, blot out cosmogony,/ Geology,

ethnology, what not,/ (Greek endings, each the little passing

bell/ That signifies some faith's about to die),/ And set you

square with Genesis again, -" (Robert Browning, Bishop

Blougram's Apology, 1854-5, lines 678-684)

(4) HP to Nicholas Longworth,

April 22 1839 (Donald Reynolds, Hiram Powers's Ideal

Sculpture, New York, Garland Press, 1977, p.133).

(5) The Death of Abel.

In five books. Attempted from the German of Mr. Gessner (by

Mary Colyer), London, 1799, pp.52-55. I am grateful to Claudia

Vitale for help in tracing this source.

(6) HP to Lynden Ryder, May 1839

(Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers, Vermont Sculptor,

1805-1873, Newark, University of Delaware Press, 1991,

I, p.115, p.182). Powers declined Longworth's commission when

he learned that the actual carving of the marble for this

statue would be entrusted to local stone workers in Cincinnati

(Wunder, op.cit., I, p.112).

(7) HP to John Preston, 20 May

1840 (Wunder, op.cit., I, p.183).

(8) HP to Sidney Brooks, 4

December 1849, Wunder, I, p. 187.

(9) D.K.S. Hyland, Lorenzo

Bartolini and Italian Influences on American Sculptors in

Florence (1825-50), Newark, Univesity of Delaware Press,

1980, p.216.

(10) "The hair is parted &,

passing over the ears, falls in wavy masses down the back, and

terminates among the flowers of a cluster of plants, around

which, after encircling her feet, the serpent appears, with

his head projecting in front, just below the right hip &

looking cautiously up into her face for whatever may have been

his means of seduction." HP to Henry Lea, 10 January 1841

(Wunder, op.cit., I, p. 182).

(11) "Eve is quite 'naked', and

she does not appear in the least 'ashamed'. It was very wrong

to make her so, but it is too late to correct an error, which

Eve herself discovered in the season for fig leaves and

managed to set all right where all was wrong before." HP to

Sidney Brooks, 4 December 1849 (Reynolds, op.cit., p.158). Cf.

"her purification (from original sin) she underwent under

water at Carthagena would have been the last of her trials."

HP to Sidney Brooks, 17 October 1850 (Wunder, op.cit., I,

p.190).

(12) Wunder, op.cit., I, p.305.

(13) "I tell you, hopeless grief

is passionless/ ...Deep-hearted man, express/ Grief for thy

Dead in silence like to death:-/Most like a monumental statue

set/ In everlasting watch and moveless woe,/ Till itself

crumble to the dust beneath./ Touch it: the marble eyelids are

not wet;/ If it could weep, it could arise and go." Sonnet on

Grief.

She wrote to Anna Jameson that

the death of her brother had turned her "...white-souled, the

past has left its mark with me for ever." EBB to Anna Jameson,

26 February 1852; Kenyon, II, 1897, p.58.

(14) EBB to Arabel, 29-30 May

1847 (The Brownings' Correspondence, ed. P. Kelley and

Scott Lewis, 14, Waco, Texas, Wedgestone Press, 1998, p.216)

(15) "[A] peculiar reference to

Eve's allotted grief, which, considering that self-sacrifice

belonged to her womanhood, and the consciousness of

originating the Fall to her offence, - appeared to me

imperfectly apprehended hitherto, and more expressible by a

woman than a man." Preface to A Drama of Exile, 1844,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Poetical Works, I,

London, Smith, Elder & Co., 1890, p.xii.

(16) W.J. Hubard to HP, 20

September 1839. Dentler typescript, p.60.

(17) "Adam and Eve in the

morning go forth to their labours, which Eve proposes to

divide in several places, each laboring apart: Adam consents

not, alledging the danger, lest that enemy, of whom they were

forewarn'd, should tempt her found alone: Eve loath to be

thought not circumspect or firm enough, urges her going apart,

the rather desirous to make trial of her strength." The

argument of Book IX, John Milton, Paradise Lost.

"Eve

separate he spies...oft stooping to support/ Each flow'r of

slender stalk.../ Hung drooping unsustain'd; them she

upstays/ Gently with myrtle band, mindless the while/

Herself, though fairest unsupported flower,/ From her best

prop so far, and storm so nigh." John Milton, Paradise

Lost, IX, 424 ff.

(18) Nathaniel Hawthorne,

Passages from the French and Italian Note-books of

Nathaniel Hawthorne, quoted in Wunder, op.cit., II,

p.182.

(19) "Her unadorned golden

tresses wore/ Dishevel'd.." John Milton, Paradise Lost,

IV, 304; "..not with indented wave,/ Prone on the ground, as

since, but on his rear,/ Circular base of rising folds, that

tower'd/ Fold above fold a surging maze, his head/ crested

aloft...erect/ Amidst his circling spires.." John Milton, Paradise

Lost, IX, 495 ff.

(20) John Flaxman, Lectures

on Sculpture, London, John Murray, 1829, pp.336-8.

Evidence for Powers's familiarity with this work is given in

the exhibition catalogue Hiram Powers' Paradise Lost,

Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York, 1985, p. 13, p. 28

(note 15).

(21) HP to George Peabody, 24

October 1861 (Reynolds, op.cit., p.202).

(22) "Nude, as it [La Penserosa]

now appears, it would do for an Eve After the Fall, provided

there was shade of grief on the face. The subjects are not

unlike, so far as the mere form is concerned." HP to James

Lenox, 27 December 1853 (Reynolds, op.cit.,p. 180).

(23) Rosina Bulwer Lytton's

wrote in the Court Journal of 8 May 1841 that Powers

had made two attempts at 'the ideal': "a statue of Eve, still

in the clay....beautifully moulded...But the attitude is

ungraceful, that of the right elbow resting on the hip, as she

holds out the apple, ... the face itself...has the fault of

being too discreet, and expressing nothing. Why does not such

an artist leave dull realities, and draw a little upon the

imagination that I feel sure he must possess!"

(24) 'It is not an ideal,

poetical Eve that he has presented to us; - not Milton's Eve,

but the living Eve of the Bible.' Lady Stamer, 8 February 1842

(Wunder, op.cit., I, p.185).

(25) HP to Kellogg, 18 January

1848 (Wunder, op.cit., I, p.187).

(26) HP to Sidney Brooks, 4

December 1849 (Wunder, op.cit., I, p.187).

(27) HP to Nathan Denison

Morgan, 6 December 1871 (Wunder, op.cit., I, p.305).

(28) T.A. Trollope, Some

Recollections of Hiram Powers, Lippincott's Magazine of

Popular Literature and Science, 4, February 1875; quoted

in Wunder, op.cit., I, p.55.

(29) "Eve looks primal. There is

not one hour's experience in her new soul, beaming out of her

large, innocent eyes. I am sure she has not yet tasted the

apple she holds in her hand, and knows nothing whatever about

good and evil." Sophia Hawthorne, Notes in England and

Italy, 1869, p.366.

(30) HP to Mary Duncan, 7

September 1857; quoted in C. Colbert, "Each Little Hillock

hath a Tongue" - Phrenology and the Art of Hiram Powers, Art

Bulletin, XVIII, June 1986, p. 291.

(31) "A nude statue is an

unveiled soul, and not a naked body." HP to Elizabeth Barrett

Browning, 7 August 1853; D. Reynolds, The "Unveiled Soul":

Hiram Powers's Embodiment of the Ideal, Art Bulletin,

59, September 1977; K. Gaja, "Scrivendo nel marmo": lettere

inedite tra Elizabeth Barrett Browning e Hiram Powers, Antologia

Vieusseux, 25-26, 2003.

(32) This dimension is explored

by Claudia Vitale in her paper 'La pietra e la parola:

Elizabeth Barrett Browning a Firenze', with special reference

to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's sonnet Hiram Powers's

Greek Slave.

(33) Bayard Taylor to HP, 1

October 1845; HP to Bayard Taylor, 9 October 1845 (Wunder,

op.cit., I, p.190-191).

(34) "[A]nd the conceit occurred

to me to let the marble, which while living he made so

eloquent, pronounce his eulogy. TO HIRAM POWERS

..and I bemoan/ With you, - yes,

I, poor, cold, but grateful stone!/ Would you the true

interpretation seek?/ His fingers gave me life to breathe and

speak:/ Raised me from earth, and let my spirit free;/

The soul God gave him, he

breathed into me." Thomas Ball, quoted in Wunder, op.cit., I,

p.353.

(35) "Clearly Jehovah would not

have placed two trees in a garden, and one for a stumbling

block, unless they had some spiritual meaning. Nor does it

accord with divine justice that both Adam and his wife should

be cursed because they ate of the fruit of some tree; nor that

the curse should adhere to all their posterity, and thus that

the whole human race should be condemned for a fault involving

no evil lust nor badness of heart." Emanuel Swedenborg, The

True Christian Religion, London, J.M.Dent, 1933, p. 537

(Vera Christiana Religio, 1771).

(36) "Zerah: Heaven is dull,

Mine

Ador, to man's earth.

...The

winding, wandering music that returns

Upon

itself, exultingly self-bound

In

the great spheric round

Of

everlasting praises;" The Seraphim, Elizabeth

Barrett

Browning's

Poetical Works, op.cit., I, p.133. The poem is

discussed in Isobel Armstrong's essay Casa Guidi Windows:

spectacle and politics in 1851 (ed. A. Chapman and J.

Stabler, Unfolding the South. Nineteenth-century women

writers and artists in Italy, Manchester University

Press, 2003, p.68-9).

(37) "The angel of death call'd

forth the soul of ABEL from the ensanguin'd dust. It advanc'd

with a smile of joy. The more pure and spirituous parts of the

body flew off, and mixing with the balsamic exhalations,

wafted by the zephyrs from the flowers which sprung up within

the compass irradiated by the angel, environ'd the soul,

forming for it an etherial body." Gessner, op.cit., p.165.

(38) Dentler typescript, p.79.

(39) "Eve has played me almost

as bad a prank as she played my greatest of grandfathers...The

fact is I found her in a highly putrefied state wedged in

among the rocks at Seravezza, and after taking her out and

doing all that lay in my power...to restore her to life and

her former personal attractions, in short - after spending

some fourteen months in this charitable manner and paying her

passage to America, what do you think she has done? Why in a

fit of mortification and shame brought on partly by some of Mr

Beecher's remarks upon the nudity of the Slave, and mostly by

a sense of superior modesty and innocence of her

granddaughters, she forgets her gratitude.... & plunged

overboard in the midst of a shoal of mermaids, who have since

adopted her as their Queen..." HP to Mrs Salmon, 15 April 1850

(Dentler typescript, p.62).

© Katerine Gaja, 2004

THE INSCRIPTION ON THE TOMB OF WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR/

DELL'EPIGRAFE SULLA TOMBA DI WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

MARK ROBERTS

§°WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR/ ENGLAND/ Landor/ Gualtiero Savage/ / Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 17 Settembre/ 1864/ Anni 90/ 879/ Walter Savage Landor, l'Angleterre/ GL23777/1 N° 348 Burial 19/09, Rev Pendleton/ Freeman, 223/ Thomas Adolphus Trollope, What I Remember, II.244-262, notes Landor and the Garrows knew each other well from Devon days, gives Landor's letter about Kate Field's Atlantic Monthly article which mentions the Alinari photograph of himself/ IN MEMORY OF/ WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR/ BORN 30th OF JANUARY 1775/ DIED 17th OF SEPTEMBER 1864/ AND THOU HIS FLORENCE TO THY TRUST/ RECEIVE AND KEEP/ KEEP SAFE HIS DEDICATED DUST/ HIS SACRED SLEEP/ SO SHALL THY LOVERS COME FROM FAR/ MIX WITH THY NAME/ MORNING STAR WITH EVENING STAR/ HIS FAULTLESS FAME/ A.G. SWINBURNE/ F9E °=Gen. Pier Lamberto Negroni Bentivoglio

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife;

Nature I loved, and next to Nature, Art.

I warmed both hands before the fire of Life:

It sinks, and I am ready to depart.Walter Savage Landor

after Mrs Browning died in the summer of 1861 her maid Wilson, now the signora Romagnoli, moved into the ground floor rooms to look after the old man.

Nel novembre 1859, Walter Savage Landor, oramai un vecchio ottantaquattrenne inasprito, confuso e squattrinato, trovò alloggio – per intercessione dell’amica Elizabeth Barrett Browning - in un piccolo appartamento al primo piano di via Nunziatina 2671. Questa sarebbe stata la sua ultima dimora per i seguenti cinque anni e qui sarebbe morto. L’appartamento era composto da tre piccole stanze e da uno studiolo per i libri: situazione molto diversa da quella che aveva contraddistinto i suoi precedenti soggiorni italiani negli anni 1820 e 1830 – allorché aveva vissuto con un certo fasto alla Villa della Gherardesca (più tardi chiamata “Villa Landor” da Daniel Willard Fiske e oggi nota come “La Torraccia”). Alla morte di Elizabeth Browning, nel 1861, era venuta ad abitare al piano terreno dell’edificio in via Nunziatina , la governante dei Browning, Wilson (adesso “signora Romagnoli”) che avrebbe avuto il compito di vegliare sul vecchio poeta.

Landor’s thoughts turned increasingly to his own demise and the arrangements that would have to be made. His general plan was to be buried in Widcombe churchyard, but in October he received a letter from the vicar saying that if he still wanted to be buried there his grave would have to be made at once, as the burial ground was to be closed. The following January he mentioned the problem of Widcombe churchyard in a letter to the grieving widower Browning, who had other things on his mind, but who evidently encouraged Landor to give up the expensive notion of an English funeral. (Browning was very practical about money, and had earlier scotched a scheme hatched by Landor to make some building alteration to the terrace in via Nunziatina: ‘On this terrace’, the old man had threatened to his friend Kate Field, ‘I shall spend all my October days, and–and–all my money!’) Later in 1862 Landor wrote to Browning: ‘Your letter has induced me to rest my bones in Florence, where my two sons, Walter and Charles, will defray the expenses of my funeral...my express orders are that only the small common stone covers my body, with the inscription–

I pensieri di Landor, adesso, spesso erano volti a considerare il momento della propria scomparsa e di come avrebbero dovuto esserne gestite le circostanze. In linea di principio desiderava essere sepolto nel terreno adiacente alla chiesa di Widcombe – ma il suo piano fu alterato da una lettera ricevuta in ottobre di quello stesso anno. Landor vi veniva informato che se avesse ancora avuto il desiderio di essere sepolto a Widcombe, avrebbe dovuto far eseguire subito la propria tomba, giacchè le sepolture in quel cimitero sarebbero state dismesse. Nel gennaio seguente Landor accenna in una lettera inviata a Robert Browning la questione del cimitero di Widcombe. Questi, ancora addolorato per la scomparsa della moglie e preso da tutti altri problemi, peraltro pare averlo incoraggiato a rinunciare all’idea di un costoso funerale in Inghilterra. (Browning aveva un atteggiamento molto pragmatico nei confronti del denaro e aveva cercato già di inibire un progetto di alterazione della terrazza di via della Nunziatina che Landor aveva annunciato all’amica Kate Field con la frase: “Vedrà finire i miei giorni e tutti i miei soldi”). Più tardi, nel corso del 1862, Landor scriveva a Browning: “La vostra lettera mi ha indotto a desiderare che le mie ossa riposino a Firenze: qui i miei due figli, Walter e Charles, faranno fronte alle spese del funerale…Il mio ordine esplicito è che solo una comune pietra tombale ricopra il mio corpo con la seguente iscrizione:

This prediction was too pessimistic, in the event, and indeed the following year he published yet another book of poems, entitled Heroic Idylls, which came out in October 1863 with a dedication to Edward Twisleton, to whom Landor had entrusted the MS a few months previously.WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

BORN JANUARY 30, 1775

DIED . . . 1862'

La predizione si rivelò in effetti eccessivamente pessimistica: infatti l’anno seguente Landor pubblicò un ulteriore libro di poesie (Heroic Idylls). Il volume uscì nell’ottobre 1863 con una dedica a Edward Twisleton – la persona cui Landor aveva affidato il manoscritto pochi mesi prima.

Landor’s grave in the non-catholic cemetery in Piazzale Donatello currently has a stone with an inscription consisting of lines in memory of the poet composed by Algernon Charles Swinburne. This modern inscription is not what Landor wanted, as we have seen, nor is it what he originally got, but it is nevertheless fitting and appropriate, as I shall try to show.

Nel cimitero non cattolico di Piazzale Donatello, la tomba di Landor attualmente reca un’iscrizione in memoria del poeta composta da Algernon Charles Swinburne. Questa lapide non rappresenta, come abbiamo visto, né ciò che Landor desiderava né quella che ricevette al momento della morte. Cionondimeno l’iscrizione ci appare appropriata e cercherò di dimostrarne la ragione.

In February 1864 the young Algernon Swinburne travelled to Paris in company with his friend Lord Houghton, as Richard Monckton Milnes had by then become. After a few days he left Houghton in Paris and pressed on to Italy, armed with Houghton’s letter of introduction, specifically in order to pay homage to the great Walter Savage Landor in Florence. The twenty-six-year-old Swinburne had a shock of red hair, but otherwise had a great deal in common with Landor, or so he thought. Both were hellenists, both were atheists and republicans, both idolised Percy Bysshe Shelley. Swinburne was entranced by the notion of receiving the poetic torch from one who had been born in 1775 and might easily have known Shelley. (In fact Landor never did meet Shelley, because he foolishly avoided him on account of his reputation for immorality, of all things, to his later regret.) Swinburne’s first meeting with Landor was not however a success. The young poet wrote to Lord Houghton on 4 March 1864:

Nel febbraio 1864 il giovane Algernon Swinburne compì un viaggio alla volta di Parigi in compagnia dell’amico Lord Houghton – il nome che, per via di ereditarietà di titoli nobiliari, adesso spettava a Richard Monckton Milnes. Dopo un breve soggiorno parigino, Swinburne lasciò l’amico e proseguì per l’Italia accompagnato da una lettera di presentazione che Houghton gli aveva fornito con lo specifico scopo di introdurlo, a Firenze, presso il grande Walter Savage Landor. Il ventiseienne Swinburne aveva una folta chioma di capelli rossi, ma sotto molti altri rispetti aveva parecchio in comune con Landor – o perlomeno così riteneva. Entrambi erano ellenisti, entrambi si dichiaravano atei e repubblicani e condividevano un’idolatria per Percy Bysshe Shelley. Swinburne era emozionato all’idea di ricevere una sorta di investitura letteraria da qualcuno che era nato nel 1775 e che avrebbe potuto facilmente aver conosciuto Shelley. (In realtà Landor non aveva mai incontrato Shelley: scioccamente, e anni dopo se ne sarebbe lamentato, lo aveva evitato apposta per via – colmo dei colmi – della sua reputazione immorale). L’incontro fiorentino fra i due, comunque, non fu un successo come è testimoniato dalla lettera che il giovane poeta scrive il 4 marzo 1864 a Lord Houghton:

With much labour I hunted out the most ancient of demigods at 93 Via della Chiesa, but (although knock-down blows were not, as you anticipated, his mode of salutation) I found him, owing I suspect to the violent weather, too much weakened and confused to realise the fact of the introduction without distress. In effect, he seemed so feeble and incompatible that I came away in a grievous state of disappointment and depression myself, fearing that I was really too late...Apparently he had thrown himself at Landor’s feet and covered his hands with kisses, and the irascible old man was more bewildered than pleased. Swinburne’s letter goes on:Con molta fatica sono riuscito a rintracciare il più antico dei semi-dei al numero 93 di Via della Chiesa ma – anche se l’accoglienza calorosa non rientrava, come mi avevate anticipato, nel suo modo di salutare - l’ho trovato, forse per via della stagione pessima, in uno stato di debolezza e di confusione tali da non permettergli di evitare la sorpresa smarrita della mia visita. Infatti mi apparve così debole e assente che io stesso venni via in uno stato deplorevole di delusione e disappunto – temendo davvero di essere arrivato troppo tardi…

Quello che il giovane Swinburne aveva fatto era stato di gettarsi ai piedi di Landor e di coprirgli le mani di baci, riuscendo a far sì che il vecchio irascibile fosse più scandalizzato che compiaciuto. La lettera di Swinburne prosegue:

I wrote him a line of apology and explanation, saying why and how I had made up my mind to call upon him after you had furnished me with an introduction...To which missive of mine came a note of invitation which I answered by setting off again for his lodgings. After losing myself for an hour in Borgo S. Frediano I found it at last, and found him as alert, brilliant and delicious as I suppose others may have found him twenty years since.(It may seem stupid of Swinburne to have got lost for an hour in Borgo San Frediano, especially as he had already been once to the house, but my guess is that people were not able to direct him very well as the name of the street had only the previous year been changed from Via Nunziatina to Via della Chiesa.) Swinburne made various protestations of devotion, and begged Landor to accept the dedication of his forthcoming book of poetry, Atalanta. Having graciously accepted, Landor insisted on giving Swinburne a painting which he said was by Correggio – ‘a masterpiece that was intercepted on its way back to its Florentine home from the Louvre, whither it had been taken by Napoleon Bonaparte.’ Unfortunately it was, like so many of Landor’s pictures, a fake.Gli ho scritto due righe per scusarmi e per spiegargli del perché e del come avessi deciso di andarlo a trovare dopo che mi avevate fornito una lettera di presentazione…A questo mio messaggio è seguito un biglietto di invito cui io ho risposto dirigendomi nuovamente verso casa sua. L’ho finalmente trovata dopo essermi perso in San Frediano per circa un’ora. Questa volta mi è apparso vigile, brillante e ameno come immagino altri lo abbiano visto nel corso degli ultimi venti anni.

(Può apparire strano che Swinburne si sia smarrito per un’ora in San Frediano – soprattutto perché già una volta era stato da Landor. La mia ipotesi è che i passanti non fossero in grado di dargli indicazioni stradali molto precise poiché, solo l’anno precedente, il nome della strada era cambiato da Via Nunziatina a Via della Chiesa). Swinburne, durante quella visita, fece atto di grande devozione al vecchio poeta e lo pregò di accettare la dedica che gli avrebbe rivolto del suo prossimo libro di poesie, Atalanta. Dopo aver benevolmente ricevuto l’offerta, Landor volle a tutti i costi dare a Swibrune un quadro che disse era di Correggio – “un capolavoro che è stato intercettato sulla via del ritorno verso la sua dimora fiorentina dal Louvre, dove lo aveva trafugato Napoleone Bonaparte”. Purtroppo, come spesso nel caso dei quadri di Landor, si trattava di un falso.

A few days after Swinburne’s second visit, and while he was contemplating a third, Landor sent him a note (addressed simply to ‘Swinburne, Esq.’):

Pochi giorni dopo la seconda visita, e mentre Swinburne ne progettava una terza, Landor gli fece recapitare un messaggio indirizzato semplicemente a “Swinburne, Esq”. Qui si diceva

My dear friend,If Swinburne was disappointed by this second rebuff, he never said so: I suspect that he had already got what he wanted. Landor did have a few more visits from other admirers. When Augustus Hare came in late May he too was confused by the change of the street name, but he identified the house because he recognised the pictures he could see through the first-floor windows, just as he remembered them in Bath. Landor was failing: earlier that month he had rang for Mrs Romagnoli at two in the morning, asking for windows to be thrown open, and for pen, ink and paper. Having written a few lines he leaned back and said ‘I shall never write again. Put out the lights and draw the curtains’.

So totally am I exhausted that I can hardly hold my pen, to express my vexation that I shall be unable ever to converse with you again. Eyes and intellect fail me–I can only say that I was much gratified by your visit, which must be the last, and I remain ever

Your obliged

W. Landor.Mio caro amico,

sono talmente esausto che appena riesco a tenere la penna in mano e riesco ad esprimere la mia contrarietà per via del mio non poter più conversare con voi. La vista e l’intelletto mi tradiscono – posso solo dire quanto mi abbia gratificato la vostra visita – che peraltro deve essere l’ultima – e resto il vostro

W.Landor

Se Swinburne rimanesse deluso da questo secondo smacco, non si è mai saputo: ritengo che considerasse di aver già ottenuto quello che desiderava. Landor ricevette ancora qualche visita dai suoi ammiratori. Ad esempio, quando Augustus Hare venne a trovarlo a maggio inoltrato, anche questi fu confuso dal cambiamento del nome della strada – ma riuscì a identificarla per via dei quadri che riconobbe attraverso le finestre del primo piano, proprio come li ricordava nella casa di Bath. La salute di Landor andava peggiorando: ai primi di maggio aveva chiamato la signora Romagnoli alle due di notte per dirle di aprire le finestre e per farsi portare penna, inchiostro e carta. Dopo aver scritto poche righe, si era accasciato dicendo “Non scriverò mai più. Spengete le luci e tirate le tende”.

Yet he was not to be trifled with. Many years before, as is well known, he had thrown a cook out of the window at the Villa Gherardesca. To show that ‘the old volcanic fire still lived beneath its ashes’, Thomas Adolphus Trollope cites another defenestration episode, from this later period, in which Landor, having finished dinner, ‘thinking that the servant did not come to remove the things so promptly as she ought to have done’, gathered everything up in the tablecloth and bundled it out of the window.

D’altra parte Landor non era tipo con cui scherzare. Molti anni prima – com’è ben noto – aveva gettato un cuoco da una finestra di Villa della Gherardesca. Per mostrare che “l’antico fuoco ancora ardeva sotto le braci”, Thomas Adolphus Trollope cita un altro tipo di “defenestrazione” del periodo più tardo. Pare che, avendo Landor finito di cenare, e “ritenendo che il maggiordomo non fosse venuto a ritirare i piatti con la sollecitudine necessaria”, egli avesse raccolto gli avanzi del pranzo nella tovaglia e ne avesse gettato il fagotto dalla finestra.

In mid September he had such a bad cold and a cough that he stayed in bed, something he never normally did. His sons Walter and Charles arrived separately to visit him on Saturday the 17th. Landor said he would take a pill for his cough, then changed his mind, then tried to take a drink, then laid down his head and died. His daughter who had not seen him for five years drove down from the Villa to view the corpse. On the evening of Sunday the 18th he was buried in the Protestant Cemetery, the service conducted by the Revd I.H.S. Pendleton, chaplain of the English church. Only Walter and Charles followed the coffin to the grave.

A metà settembre fu afflitto da un raffreddore e da una tosse così persistenti da dover restare a letto – cosa che non faceva in genere. I figli Walter e Charles vennero, ognuno per conto proprio, a trovarlo il 17 settembre, un sabato. Landor aveva detto che avrebbe preso una pastiglia per la tosse, ma poi cambiò idea e tentò di bere, infine reclinò la testa e spirò. La figlia che non lo aveva più visto nel corso degli ultimi cinque anni, venne giù dalla Villa per vegliarne la salma. La sera di domenica 18 fu sepolto nel Cimitero Protestante con una cerimonia condotta dal Rev. I.H.S.Pendleton, cappellano della Chiesa Inglese. Solo Walter e Charles seguirono il feretro fino alla tomba.

The poet’s estranged family paid for an upright headstone bearing the following inscription:

La famiglia pagò distrattamente una lapide verticale che recava la seguente iscrizione:

SACRED

TO THE MEMORY OF

WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

BORN 30TH DAY OF JANUARY 1775

DIED ON THE 17TH DAY OF SEPTEMBER 1864.

THE LAST SAD TRIBUTE

OF HIS WIFE AND CHILDREN.

The Italian stonecutter is said to have bungled the unfamiliar letter ‘w’ in the final line and to have written ‘coife’. The stone itself was of poor quality and friable, and the insincere inscription soon faded.

Si dice che lo scalpellino italiano, stravolgendo la esotica “w” della parola “wife” (moglie) abbia scritto, invece, “coife”. La pietra era di qualità scadente e friabile; l’iscrizione ipocrita presto impallidì.

In modern times (‘recently’ according to Super, who was writing in 1954) a flat marble slab has been laid over the poet’s grave, lying in the opposite direction to the body, so that it can be read more conveniently from the path. The admirers who paid for this slab – my guess is that they included Mr Christopher Pirie-Gordon – took their cue from the concluding pages of Forster’s celebrated biography of Landor, and quoted two of the thirteen quatrains of Swinburne’s poem ‘In Memory of Walter Savage Landor’, published in Poems and Ballads:

In epoca moderna (“recente” secondo Super che scriveva nel 1954) una lastra di marmo è stata posta sulla tomba del poeta, in direzione opposta alla giacitura del defunto, in maniera da renderne più agevole la lettura. Gli ammiratori che hanno finanziato questa lapide – penso che fra di loro ci fosse Christopher Pirie –Gordon – hanno preso ispirazione dalle pagine finali della nota biografia dedicata a Landor da Forster e hanno utilizzato due delle tredici quartine che Swinburne, aveva scritto nella poesia “In Memory of Walter Savage Landor” e che è inclusa nel suo Poems and Ballads.

AND THOU, HIS FLORENCE, TO THY TRUST

RECEIVE AND KEEP,

KEEP SAFE HIS DEDICATED DUST,

HIS SACRED SLEEP.

SO SHALL THY LOVERS, COME FROM FAR,

MIX WITH THY NAME

AS MORNING-STAR WITH EVENING-STAR

HIS FAULTLESS NAME.

This is an apostrophe to Florence, so ‘thy lovers’ refers to the city’s lovers, the artistic and poetical pilgrims who still come, even at this distance in time, to pay their homage. The point about the ‘morning-star’ and the ‘evening-star’ is of course that they are both the same thing, both the planet Venus: this astronomical fact was well known to the ancients, whose poets nevertheless speak of two different heavenly bodies, Eosphoros and Hesperos.

Si tratta di un saluto a Firenze così che “thy lovers” si riferisce agli innamorati della città – a quanti ancora oggi compiono un pellegrinaggio artistico e poetico e, dopo tanto tempo, depongono il loro omaggio. Vale la pena osservare che “la stella del mattino” e la “stella della sera” sono la medesima stella, e cioè il pianeta Venere. Questo dato astronomico era ben noto nell’antichità, ma ciononostante quei poeti parlavano di due diversi corpi celesti – Eosforo e Espero.

Swinburne’s lines, the best ones in the poem, are in fact a passable imitation of Landor’s lapidary manner, which at its best achieved a chiselled finality of expression reminiscent of the finest pages of the Greek Anthology. Here is the very well known ‘Dying speech of an old philosopher’:

I versi di Swinburne, i più belli della poesia, sono in effetti una accettabile imitazione dei versi lapidari di Landor che, nel loro miglior momento, raggiungono una finissima persuasività espressiva e tali che ricordano le più scelte pagine dell’Antologia Greca. Ecco la notissima strofa Landoriana dal DYING SPEECH OF AN OLD PHILOSOPHER:

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife;When Swinburne heard the news of Landor’s death he was rather irritated, as Atalanta had not yet been published and so could not be proudly shown to its dedicatee. To Paulina Lady Trevelyan he wrote on 15 March 1865 that ‘Mr Landor’s death...was a considerable trouble to me as I had hoped against hope or reason that he who in spring at Florence had accepted the dedication of an unfinished poem would live to receive and read it...As it is he never read anything of mine more mature than Rosmund’.

Nature I loved, and next to Nature, Art.

I warmed both hands before the fire of Life:

It sinks, and I am ready to depart.Non ho gareggiato con nessuno, poiché nessuno era degno della mia rivalità;

La Natura ho amato e accanto a questa, l’Arte.

Entrambe le mani ho scaldato al fuoco della Vita:

questa si sta spengendo e sono pronto a prenderne commiato.

Allorché Swinburne apprese la notizia della morte di Landor, ne rimase alquanto irritato. Infatti il suo Atalanta non era ancora stato pubblicato e pertanto non avrebbe potuto farne sfoggio con il dedicatario. Scrisse a Paulina, Lady Trevelyan, nel marzo 1865 “La scomparsa di Landor è stata per me fonte di un certo disappunto poiché avevo sperato – aldilà di ogni ragionevolezza – che colui che in primavera a Firenze accettava la dedica di un poema non finito, ancora in vita al momento della sua pubblicazione, avrebbe potuto riceverlo e leggerlo…Cosi’ come sono andati gli eventi /Landor/ non ha mai letto mai una mia opera più complessa di Rosmund”.

A decade after Landor’s death, Swinburne was an established poet when he wrote to Edmund Clarence Stedman (23 February 1874), giving his considered reflections on the whole incident:

Una decina di anni dopo la scomparsa di Landor, Swinburne che aveva raggiunto nel frattempo un’affermata posizione nel mondo letterario, così scriveva delle sue impressioni maturate sull’intero episodio a Edmund Clarence Stedman (il 23 febbraio 1874):

...I remember well how pleasant and how precious, for all his high self-reliance and conscious autarkeia, the sincere tribute of genuine and studious admiration was even at the last to the old demigod with the head and the heart of a lion. I have often ardently wished I could have been born (say but five years) earlier, that my affection and reverence might have been of some use and their expression found some echo while he was yet alive beyond the rooms in which he was to die. The end was very lonely, and I fear the last echo of any public voice that reached him from England must have been of obloquy and insult.© Mark Roberts, 2004, trad. Margherita Ciacciricordo con piacere quanto, fino all’ultimo, – malgrado il suo alto sentimento di sé e la ostentata autosufficienza – il tributo di un’ammirazione sincera e colta fosse prezioso per il semi-dio, dalla testa e dal cuore di un leone. Ho spesso ardentemente auspicato di essere nato, diciamo, cinque anni prima così che il mio affetto e la mia devozione gli potessero essere di aiuto e la loro eco avesse modo di diffondersi – lui ancora in vita – oltre le stanze che avrebbero visto la fine dei suoi giorni. Il trapasso avvenne in una grande solitudine e temo che l’ultima eco di una voce pubblica che gli arrivasse dall’Inghilterra fosse carica di insulti e contumelie.”

Much better than this image of WSL is one taken later by Alinari, now lost, but which served as frontispiece to a book on him. It shows him with the white mane of hair and beard looking like King Lear. If anyone has a copy could they please scan and send to JBH for inclusion here.

While Laurence Hutton, Literary Landmarks of Florence (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1897), has the following nineteenth-century photograph of the tomb,

noting that its 'inscription simply bears his name and records the fact that it is "The Last Sad Tribute of his Wife and Children".

Here we give Walter Savage Landor's present tombstone immediately before its cleaning, four years ago, the inscription still being legible:

Then Walter Savage Landor's tomb as it is now, after the so-called 'cleaning', the inscription becoming almost illegible:

Contributions were received for this cleaning from

descendants and others. The stonemason worked very rapidly,

for a very brief time, with well water, more lead letters

became dislodged and the tomb surface immediately

deteriorated. Opificio delle Pietre Dure says to use neither

tap nor well water, only distilled water, as the chemicals in

the other two eat into the marble. Fortunately, this is not

the original tomb but its replacement. It is no longer shown

to visitors because of the deterioration. It may no longer be

possible to save the present tombstone, even through employing

an expert restorer to undo this damage.

WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

WEBSITE:

Recordings of Gebir I, Gebir II || Essay 'Walter Savage Landor' in New Spirit of the Age || Jean Field,

'Walter Savage Landor's Warwick'

|| 'Black and Red Letter Chaucer' || Kate Field, Atlantic

Montly, 'The Last Days

of Walter Savage Landor' || Mark

Roberts, 'The Inscription on

the Grave of Walter Savage Landor' || Alison Levy,

'The Widow of Walter Savage

Landor' || Kristin Bragadottir, 'William Morris and Daniel

Willard Fiske' (Villa Landor) || Piero Fusi,

'A. Henry Savage Landor'.

BOOKS AND BODIES, IMPRINTING MEMORY IN FLORENCE

WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR'S WIDOW, ARNOLD SAVAGE LANDOR'S MOTHER

LIBRI, CORPI, INCISIONI DI MEMORIA IN FIRENZE

LA VEDOVA DI WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

ALLISON LEVY, WHEATON COLLEGE

*° ARNOLD SAVAGE LANDOR/ ENGLAND / Landor/ Arnold/ [Savage]/ Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 6 Aprile/ 1871/ Anni 52/ 1127/ Arnault Landor, l'Angleterre/ Freeman incorrectly identifies as Fanny Trollope, 237-239/ SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF ARNOLD SAVAGE LANDOR ESQ./ BORN 5TH OF MARCH 1818/ DIED 2nd OF APRIL 1871// M. AUTERI POMAR 1873// M. AUTERI POMAR 1873/M.Auteri Pomàr [Sculpted figure of grieving mother, back turned to and farthest from Republican husband's tomb, and having the coat of arms and the crest of a 'savage']/ A4T(69)/ M.Auteri Pomàr/

Les yeux de Corinne étaient baissés en achevant cette prière, et ces regards furent frappés par cette inscription d'un tombeau su lequel elle s'était mise à genoux: - Seule à mon aurore, seule à mon couchant, je suis seule encore ici.IntroductionMadame de Staël, 'Le séjour à Florence', Corinne ou Italie

Today, I will focus on commemorative practice and visual imagery, exploring in depth the role and representation of the widow. Inspired by this year’s conference theme – the printed book in connection to Florence – I read the widow’s body precisely as a text, as a metaphorical memory book. Yet I also suggest that we read between the lines of these visual documents insofar as the widow’s body, in ritual and in representation, offers up a complex and complicating relationship between memory, mourning and masculinity. Following a survey of early modern widowhood and visual culture, primarily in sixteenth-century Florence, I discuss the nineteenth-century tomb of Arnold Savage Landor or, rather, the provocative figure of his grieving widow, Julia, who both perpetuates and complicates masculine memory in the English Cemetery.

Argument and Methodology

I begin with a few words about my methodology.

My argument works with the premise that early modern

masculinity was inherently anxious. That anxiety, citing Mark

Breitenberg on the situation in England, ‘so endemic to

patriarchy that the issue becomes not so much its

identification but rather an analysis of the discourses that

respond to it,’ is also ‘an instrument (once properly

contained, appropriated or returned) of [patriarchy’s]

perpetuation.’2 Yet if the fear of being forgotten

necessitated a set of what he calls ‘compensatory or

transferential strategies,’3 that memorial endeavor was more than just one

of benign self-preservation. We also have to recognize a

gender politics at work, even if it frequently worked against

itself.

Historically, strategies of deferral or transcendence have been consciously devised as a response to what Henry Staten calls thanato-erotic anxiety – the fear, within the dialectic of mourning, not of loss of object but of loss of self.4 The fear of one’s own death and the subsequent fear of being forgotten could and did result in auto-mourning – a premature and self-inflicted process of grieving. However, this initial act is eventually and vengefully transferred onto the bodies of women, for it is the woman’s sexuality that undermines the man’s authority, an idea Staten refers to as ‘thanatoerotophobic misogyny.’ By such a process, the social designation of women as primary mourners does much to allay fears and alleviate anxiety. For example, within this cultural environment, a husband might rightfully presume that his wife will not only mourn him but also mourn him properly (that is, sincerely and for the remainder of her life), contributing to his expectations of a so-called ‘good death.’

But for all that widowhood promises – from perpetuity to transcendence – it is undermined by its very performativity and mere prevalence. A critical examination of the realities of widowhood, both during and after mourning ceremonial, reveals a marked discrepancy between the rigidity of expectation and the ambiguity of experience. The death ritual stands as a cultural mechanism designed and performed in order to reaffirm social order after a rupture in the natural order of things. As the ritual process unfolds, social structures and hierarchies, including gender roles, are re-asserted. Thus, the culturally designated primary mourners assume the greater part of public grieving, reminding the living of their duties to the dead. Yet ritual, though certainly authoritative, is, by its very nature, artificial. As carefully scripted as ritual must be and as well concealed as the subtext of this cultural maintenance program might be, it is precisely that basic, underlying element of constructedness and the inevitability of interpretation that leads to ritual failure. A more grave deficiency is the uncertainty of mourning after ceremonial, when supervision of the primary mourners, outside of the public sphere, proved more difficult.5 For example, widows simply remarried, not all of them but enough that, as Christiane Klapisch-Zuber has recorded, the consistently uncertain social, economic and interfamilial mobility of approximately 25% of the adult female population in Florence caused a heightened degree of ‘anxiety among men.’6 Thus, if the widow simultaneously remedies and aggravates the memorial situation – her role just as tenuous as memory itself – what was the alternative? In other words, anxiety re-instated (if ever alleviated), how will the early modern subject ensure his memory?

Among those ‘compensatory or transferential strategies’ operating in the early modern period, I necessarily read portraiture as central to the memorial task. Of course, already in the fifteenth century, Alberti famously opined that painting ‘makes the dead seem almost alive.’7 But before then and since then, so many have understood the obvious connection between portraiture and commemorative practice.8 Appropriating Samuel Cohn’s critical response to recent scholarship, aptly entitled, ‘Collective Amnesia,’ I make the case for my own argument; he writes, ‘With few exceptions, discussions of the instruments and strategies for family memory in Renaissance Florence have been presented in an ideological vacuum. That is to say, they have not explored the other side of the coin – forgetfulness.’9 It is, precisely, a rhetoric of forgetting that structures my contribution to the field. Specifically, I wish to nuance our understanding of Renaissance portraiture as something complexly generated within a discourse of male anxiety and pre-mortuary mourning. In sum, I argue that portraiture could defer memory loss or, at the very least, pictorially console the subject against his own potentially unmourned death.

Widowhood and Visual Culture

Whereas recent studies of early modern

widowhood by social, economic and cultural historians have

called attention to the often ambiguous, yet also often

empowering, experience and position of widows within society,

my work considers the distinct and important relationship

between widowhood and representation.10 I read

widowhood as a catalyst for the production of a significant

body of visual material – representations of, for and by

widows, whether through traditional media, such as painting,

sculpture and architecture, or through the so-called ‘minor

arts,’ including popular print culture, medals, religious and

secular furnishings and ornament, costume and gift objects. A

careful and critical look at this unique and understudied

correlation can offer valuable insight into the fashioning and

re-fashioning of individual, family and civic identity, memory

and history. In sum, I wish to demonstrate some of the ways in

which critical visual analyses can nuance the socio-cultural,

historic, economic and psychological frameworks in which

widowhood was constructed, celebrated, censored and

commemorated, allowing us to recognize and appreciate the

complexity and contradiction, the iconicity and mutability,

and the timelessness and timeliness of widowhood and

representation.

A sixteenth-century portrait by Pontormo of Maria Salviati, the mother of Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, provides insight into the ways in which imagery could both present and perpetuate mourning models.11 Dressed in black and depicted with a somber expression, this widow comforts, or rather guides, her young child, whose appearance, complete with pensive gaze, echoes that of the exemplary mother. In this mother-and-child double portrait, the husband gains immortality through both his own commemorative image (referenced by the memorial medal in her left hand) and that of his dutiful wife, who, via his representation, is continually reminded of her role and responsibility as his widow.

Other didactic images include portraits of widows that contain representations of books – open and/or closed, legible and/or illegible – such as another portrait, still of Maria Salviati, by Pontormo.12 I read this and similar portraits against a particular set of texts – conduct books printed in Florence governing the comportment of wives and widows, such as the Book on the Widow’s Life of 1491 by the Dominican friar, Girolamo Savonarola.13 Such books, equally prescriptive and proscriptive, were not printed merely as impartial cultural documents but often as preconceived directives. Thus, the inclusion of the printed book within the visual text underscores the didactic function of widow portraiture, inviting us to extend the memorial narrative even further, allowing for a metaphorical re-reading of the widow’s body precisely as a memory book. Yet this same productive juxtaposition of book and portrait, word and image, demands that we read ever more carefully between the lines of visual and verbal memorial texts.

If the above example identifies the widow, or at least her didactic representation, as conforming to social demands, the next will shift the focus, revolving around the question of agency and examining the various ways in which the widow could manipulate her newly acquired social status by rejecting or circumventing the ideal models described thus far. In so doing, via public and private, contemporary and, even, posthumous imagery, she subtly, though successfully, could re-present herself. For example, we might consider patronage projects undertaken upon widowhood: large-scale sculptural and architectural commissions that were intended to record family history and masculine memory and, in some cases, even the widow’s own identity. Upon widowhood, some women occupied a new and potentially very powerful socioeconomic position, allowing for an often-monumental manner of marking memory. For others, the circumstance was hardly one of power but of promise; in other words, the uncertainty of a widow’s future economic situation frequently cast her in a prominent, even if temporary, role. From managing the household to doing business outside of that domestic space, financial and administrative duties generally fell under the control of the widow. A fresco by the school of Ghirlandaio in the Florentine oratory of San Martino depicts a widow assisting the notary who takes an estate inventory following her husband’s death.14 While her particular economic status, present or future, cannot be securely determined, clearly her role is central at this pivotal moment. Of course, for some widows that moment was not at all short-lived, allowing for unique expressions of memory – and power.

Case Study: Walter Savage Landor’s Grieving Widow

Concluding now with a case study

of Walter Savage Landor’s widow, grieving not over her husband

but her son, I continue to explore the particular, often

ambiguous, status of widowhood and mourning in Florence,

suggesting that the very performativity of the widow within

and beyond ritual, either sixteenth-century or

nineteenth-century, and the multivalence of subsequent

representation cannot but result in a precarious identity and

memory for both mourner and mourned.

The tomb of Arnold Savage Landor (1819-1871), Walter and Julia Savage Landor's son, in the English Cemetery, can be found on the northeastern slope, or to the right of the central path (Figure 1).15

The work of Michele Auteri Pomàr, the monument is characterized by the large-scale sculpture of Landor’s wife, Julia (Figure 2).

Her effigy defines this monument, though she herself is buried elsewhere, in the Cimitero agli Allori (d. 1879). Still, it is precisely her body – both absent and present in the English Cemetery – that interests me most. As primary mourner, she plays a critical role in maintaining her husband’s and her son's memory; standing in (or, in this case, kneeling) for the one she mourns, her presence marks his absence. Thus, she becomes a replacement, a surrogate for her son. That designation, not just a consequence of her husband’s and son's deaths but also a socio-cultural demand, materializes with our glimpse of her grieving body, simultaneously marked and marking. This widow’s portrait, then, offers up an ideal, playing an obvious key role in recording masculine memory.

Yet such representations, while preventative to some degree, can also be interpreted as problematic. In other words, the portrayal of the woman as widow might protect against memory loss, but her presence also complicates masculine memory insofar as widowhood presumes male absence. That is to say, the widow occupies a precarious position within the memorial discourse in that she is simultaneously representative of commemoration and of death itself. In light of this dualism, what are the repercussions of her dichotomous memorial role for an already anxious audience?

If representation can be read as regulatory fiction, the overcompensatory inclusion of the male portrait would seem to guarantee commemoration – at least pictorially. I have selected two examples from the English Cemetery: First, the tomb of Walter Kennedy Laurie, where his portrait is contained within an ourbouros on a tomb within a tomb, beside which his widow and orphan son grieve,

*§ WALTER KENNEDY LAWRIE/ SCOTLAND/ Lawrie/ Gualtiero Kennedy/ / Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 29 Novembre/ 1837/ Anni 31/ 164/ GL 23774 N° 60 Burial 08-12/ THY WILL BE DONE/ [grieving widow, orphan, in classical garb, with urn and funerary bust, portrait medallion within ourbouros]/ N.164/ WALTER KENNEDY LAWRIE/ BORN IN SCOTLAND 20TH AUGUST/ 1806/ DIED IN FLORENCE 28TH NOVEMBER 1837/ THE LORD GAVE AND THE LORD HATH TAKEN AWAY/ AND BLESSED BE THE NAME OF THE LORD/ B19N/ See Kennedy

second, that of Jean Claude Lagersward (1836), to be followed years later by his childless widow Sophia Hugel Lagersward (1853), here shown parting from each other:

*§° JEAN CLAUDE LAGERSVARD/ SVEZIA/ Lagersward/ Giov: Claudio/ / Svezia/ Firenze/ 12 Dicembre/ 1836/ Anni 80/ 148/ / [Sculpture of husband leaving childless wife, angel crowning him with stars with one hand, holding reversed torch with other, winged hourglass on one side, ourobouros around bee on the other] ICI.REPOSE.JEAN.CLAUDE.LAGERSVARD/ DERNIER.REJETON.DE.SA.FAMILLE/ DE S.M. LE ROI.DE. SUEDE.ET.DE.NORVEGE/ PRES. DES. COURS. D'ITALIE/ ET CONSEILLER DE SA CHANCELLERIE/ NE LA IX AOUT MDCCLVI/ MORT LE XII.DECEMBRE.MDCCCXXVI/SUEDOIS DE COEUR ET D'AME/ HABITANT L'ITALIE DEPUI 11 JUILLIET MDCCLXXXIX/ COMME SECRETAIRE DE LEGATION/ CHARGE D'AFFAIRES. ET. MINISTRE/ SOUS QUATRE DIFFERENTS REGNES EN SUEDE/ ET PENDANT LES REVOLUTIONS DE L'EUROPE/ G.N Bystrom.svedese.inv.e.scolpt. E18E/ For information on G.N. Bystrom, contact Prof. Annette Landen, Department of Art History, Lund University, Sweden

SOPHIA HUGEL LAGERSWARD/ SVEZIA/ Lagersward nata Hugel/ Sofia/ / Svezia/ Firenze/ 11 Dicembre/ 1853/ Anni 83/ 521/ Sophie Lagersward, née Hugel, Suede, rentière, Veuve de Jean Claude Lagersward, en son vivant, Ministré a S.M. le Roi de Suède près la cour de Toscana/ E18E/ see Hugel

If the widow’s body can be read as a memorial text, how, precisely, do we read Julia? We might start with her body language. Dramatically and traumatically, this body grieves inconsolably (Figure 5);

in an isolating and melancholic pose, she turns away from the surrounding monuments (Figure 6).

Perhaps not coincidentally, she also turns her back to her husband, the poet Walter Savage Landor, who had died just seven years earlier than his son (1775-1864). In fact, this cold marble shoulder is nothing new; the Landor family ties had long been severed, cut and divided much like the bisected cemetery itself (Figure 7).

Located on the southwestern slope, or to the left of the central path, is the simple, quite un-monumental tomb slab of Walter Savage Landor – without effigy, without widow, without any mournful text at all, visual or verbal (Figure 8).

Remarkably, the inscription originally contained a reference to his grieving family; it was later removed. Finally, then, those widowed words, along with his widow's suggestive body language, underscore my thesis today: that we must always read between the lines of the memorial text, no matter how blurred they may already be.

NOTES

1 Whereas the central objective of my earlier

publications was to establish widow portraiture as a new genre

of female portraiture and to explore the memorial function of

such images, my current investigations broaden the

socio-cultural context, interpreting widow portraiture as only

one pictorial element in a multi-dimensional memorial project

that also includes the use of male portraiture to ensure

masculine memory. See my articles, ‘Framing Widows: Mourning,

Gender, and Portraiture in Early Modern Florence,’ in Allison

Levy, ed., Widowhood and Visual Culture in Early Modern

Europe (Ashgate, 2003), 211-231; and ‘Good Grief: Widow

Portraiture and Masculine Anxiety in Early Modern England,’ in

The Single Woman in Medieval and Early Modern England: Her

Life and Representation, eds Dorothea Kehler and Laurel

Amtower (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and

Renaissance Studies, 2003), 258-80; and my doctoral

dissertation, ‘Early Modern Mourning: Widow Portraiture in

Sixteenth-Century Florence’ (Bryn Mawr College, 2000).

2 Mark Breitenberg, Anxious

Masculinity in Early Modern England, Cambridge Studies

in Renaissance Literature and Culture, 10 (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1996), 2.

3 Ibid.

4 Henry Staten, Eros in

Mourning: Homer to Lacan (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1995), xi-xii.

5 On the role of gender within

the death ritual, see, esp., Juliana Schiesari, The

Gendering of Melancholia: Feminism, Psychoanalysis and the

Symbolics of Loss in Renaissance Literature (Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 1992); and Sharon Strocchia, Death

and Ritual in Renaissance Florence (Baltimore: The Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1992).

6 David Herlihy and Christiane

Klapish-Zuber, Tuscans and Their Families; A Study of the

Florentine Catasto of 1427 (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1985); see also Klapisch-Zuber, ‘The “Cruel Mother”:

Maternity, Widowhood, and Dowry in Florence in the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Centuries,’ in idem, Women, Family, and

Ritual in Renaissance Italy, trans. Lydia Cochrane

(Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1985),

117-131, esp. 120.

7 Leon Battista Alberti, On

Painting, trans. John R. Spencer, rev. ed. (New Haven

and London: Yale University Press, 1966), 63.

8 Space does not permit me to

provide a synthesis of Renaissance portraiture studies but

only a small selection of those I find most compelling as well

as complicating for the present study on commemorative

practice: Patricia Lee Rubin, ‘Art and the Imagery of Memory,’

in Art, Memory, and Family in Renaissance Florence,

eds Giovanni Ciappelli and Patricia Lee Rubin (Cambridge and

New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 67-85; Alison

Wright, ‘The Memory of Faces: Representational Choices in

Fifteenth-Century Florentine Portraiture,’ in Ciappelli and

Rubin, 86-113; Jodi Cranston, The Poetics of Portraiture

in the Italian Renaissance (Cambridge and New York:

Cambridge University Press, 2000); Pat Simons, “Portraiture,

Portrayal, and Idealization: Ambiguous Individualism in

Representations of Renaissance Women,” in Language and

Images of Renaissance Italy, ed. Alison Brown (Oxford

and New York: Clarendon Press, 1995), 263-311; Richard

Brilliant, Portraiture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1991); Diane Owen Hughes, ‘Representing the

Family: Portraits and Purposes in Early Modern Italy,’ Journal

of Interdisciplinary History 17/1 (1986), 7-38; David

Rosand, “The Portrait, the Courtier, and Death,” in Castiglione:

The Ideal and the Real in Renaissance Culture, eds

Robert W. Hanning and David Rosand (New Haven and London: Yale

University Press, 1983), 91-129; and John Pope-Hennessy, The

Portrait in the Renaissance (London and New York:

Phaidon, 1966).

9 Samuel K. Cohn, Jr,