LA CITTA` E IL

LIBRO III

ELOQUENZA

SILENZIOSA:

VOCI DEL

RICORDO INCISE NEL

CIMITERO

'DEGLI INGLESI',

CONVEGNO

INTERNAZIONALE

3-5 GIUGNO

2004

THE CITY AND THE BOOK III

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

'MARBLE SILENCE, WORDS ON

STONE:

FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH

CEMETERY',

GABINETTO VIEUSSEUX AND

'ENGLISH CEMETERY', FLORENCE

3-5 JUNE 2004

I ‘FIORENTINI’ INGLESI E AMERICANI/ ENGLISH AND AMERICAN ‘FLORENTINES’

CONTINUED

Venerdì 4 giugno 2004/ Friday 4 June 2004/ Ore 9.30/ 9:30 a.m.

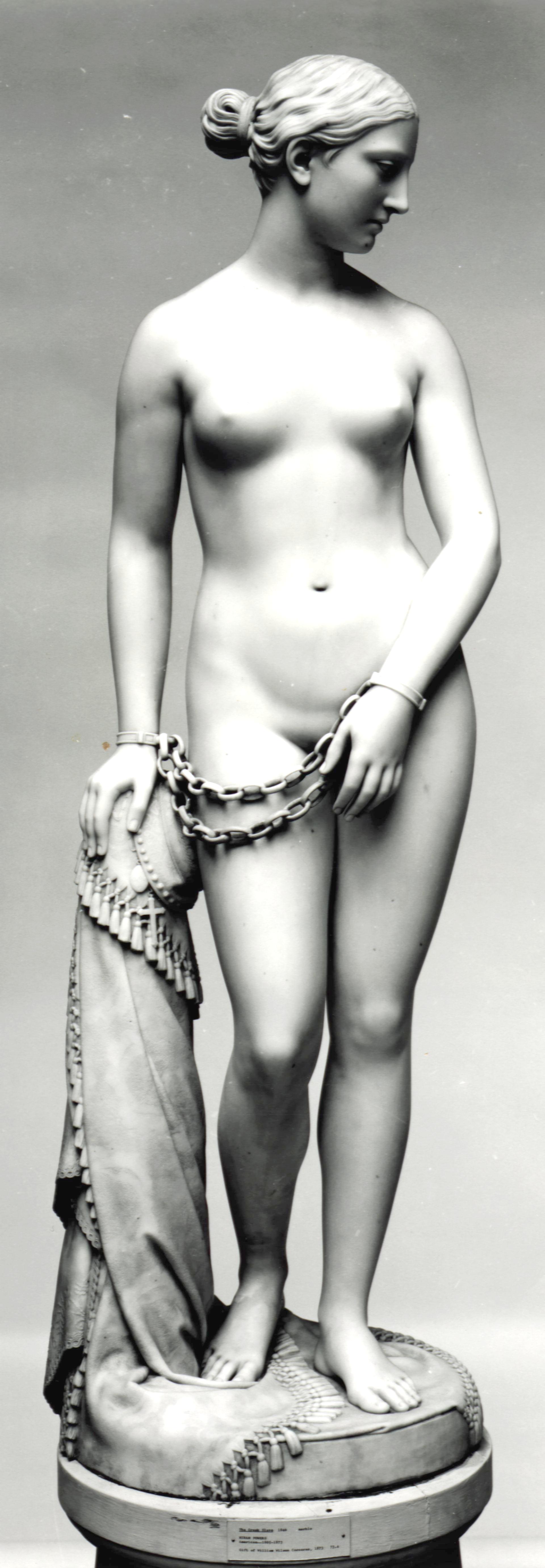

Una tomba dal nome svanito: Isa Blagden/ A Faded Inscription: Isa Blagden’s Tomb Corinna Gestri, La Nara di Prato||Clough, Horner, Zileri: tombe ricordate in un diario inglese inedito/ Tombs Linked in an Unpublished Diary Alyson Price, The British Institute of Florence||William Holman Hunt per la moglie giovane Fanny/ William Holman Hunt for His Young Wife Fanny Patricia O’Connor, The Pre-Raphaelite Society ||L'arte della memoria: John Roddam Spencer Stanhope e la tomba della figlia Mary/ The Art of Memory: John Roddam Spencer Stanhope and the Tomb of His Daughter Mary Nic Peeters, Vrije Universiteit Brussel– Judy Oberhausen, San Mateo, California|| Louisa Catherine Adams Kuhn, Florence and Chaos, 1859-1860, Robert J. Robertson || Notti bianche d'Islanda a Firenze: William Morris e Daniel Willard Fiske/ Northern Lights in Florence: William Morris and Daniel William Fiske Kristín Bragadóttir, The National Library, Reykjavik ||Marmo bianco: la vita e le lettere di Hiram Powers, un inedito di Clara Louise Dentler/ White Marble: The Life and Letters of Hiram Powers in Clara Louise’s Dentler’s Manuscript Jeffrey Begeal, The International Baccalaureate Organization

Ore 14.45/ 2:45 p.m. VISITA A CASA GUIDI/ VISIT TO CASA

GUIDI

UNA

TOMBA DAL NOME SVANITO: ISA BLAGDEN

CORINNA GESTRI

aaa

aaa

Isa Blagden, portrait owned by Lilian

Whiting, reproduced in Jeanette Marks,

The

Family

of

the

Barrett, 1938. Even her portrait is indistinct.

*§ ISABELLA BLAGDEN/ ENGLAND?/ +/135. Blagden/ Isabella/ Tommaso/ Svizzera/ Firenze/ 20 Gennaio/ 1873/ Anni 55/ 1194/ Isabelle Blagden, l'Angleterre, fille de Thomas/ GL23777/1 N°447, Burial 28/01, Rev. Tottenham/ Thomas Adolphus Trollope, What I Remember, II.173-175; Giuliana Artom Treves,The Golden Ring: The Anglo-Florentines (London: Longmans, Green, 1956), passim / ISABELLA [Cross on Flower Garland] BLAGDEN/ BORN 1816 DIED . . . 1873/ . . . WILL BE DONE . . ./F11C

ISABELLA BLAGDEN(1818-1873), is buried near her friends Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Theodosia Trollope : a love of liberty and a passionate involvement in the vicissitudes of the Italian Risorgimento cemented the friendship of these women who lived and wrote in Florence. Born in the East Indies, Isa Blagden came to live on the Bellosguardo hill in 1843. Although a talented poet and narrator (publishing as 'Ivory Beryl'), she is remembered for those human qualities which made her the gentle helpmate of R. Bulwer Lytton (Owen Meredith, the poet), the patient hostess of the old eccentric Walter Savage Landor , and an attentive observer of the Tuscan society of her times. Exotic mysticism and romanticism are mixed in her writing, now all but forgotten, effaced like the inscription on her tombstone (No. 1194). Yet her personality remains that of a lively, strong, passionate woman faithful to the most precious gift, that of friendship. L.S.

| 1 O'er the old tower, like red flame curled Which leapeth sudden to the sky Its emblem hues all wide unfurled Upsprings the flag of Italy 2 Its emblem hues! the brave blood shed The true life blood by heroes given, The green palms of the martyred dead, The snowy robes they wear in Heaven. . . . |

7 My Florence, which so fair doth be A dream of beauty at my feet While smiles above that dappled sky While glows around that rip'ning wheat 8 As fair, as peaceful and as bright Art thou as she we hear came down From Heaven in bridal robes of light Thy new Jerusalem St. John! Isa Blagden |

![]() l

fenomeno della “colonizzazione” da parte di numerosi

angloamericani di Firenze intorno alla metà dell’ottocento è

ben noto e più volte studiato. Ma consultando le

autobiografie, le memorie e le lettere degli

“anglofiorentini”, non si può fare a meno di notare il nome

di Isabella Blagden,

ovunque menzionato. Questa donna sembra essere stata l’amica

di tutti, il punto in comune fra personalità diversissime

tra loro; occupava insomma una posizione eccentrica, di

cerniera. Ma oggi Isa Blagden, autrice di romanzi e poesie e

figura centrale nell’ambiente della colonia angloamericana a

Firenze, è relegata a una posizione di margine, anzi è quasi

completamente dimenticata dalla storia della letteratura

inglese, è come scomparsa dopo un breve periodo di

notorietà.

l

fenomeno della “colonizzazione” da parte di numerosi

angloamericani di Firenze intorno alla metà dell’ottocento è

ben noto e più volte studiato. Ma consultando le

autobiografie, le memorie e le lettere degli

“anglofiorentini”, non si può fare a meno di notare il nome

di Isabella Blagden,

ovunque menzionato. Questa donna sembra essere stata l’amica

di tutti, il punto in comune fra personalità diversissime

tra loro; occupava insomma una posizione eccentrica, di

cerniera. Ma oggi Isa Blagden, autrice di romanzi e poesie e

figura centrale nell’ambiente della colonia angloamericana a

Firenze, è relegata a una posizione di margine, anzi è quasi

completamente dimenticata dalla storia della letteratura

inglese, è come scomparsa dopo un breve periodo di

notorietà.

The phenomenon of 'colonization' on the part of numerous Anglo-Americans in Florence around the middle of the nineteenth century is well known and often studied. But consulting the autobiographies, the memoires and the letters of the 'Anglo-Florentines' one cannot but note the name of Isa Blagden, which is mentioned everywhere. This woman seems to have been the friend of all, the common factor among the most diverse of them; she thus occupied an eccentric position, the networker. But today Isa Blagden, author of novels and poems and the central figure of the Anglo-American colony in Florence, is relegated to the margins, is almost forgotten in the history of English literature, as if she disappeared after a brief period of fame.

Eppure, oltre a essere l’epicentro riconosciuto della colonia anglofiorentina, la sua esperienza è fondamentale anche per capire il rapporto della donna con la difficile realtà sociale del suo periodo storico. Soggetto dalle innumerevoli contraddizioni, dalle identità multiple, un sé indefinibile, non identificabile per assoluti, ha certamente il diritto di salire sulla scena pubblica.

However, apart from being the recognized epicentre of the Anglo-Florentine community, her experience is fundamental also for understanding the relation of women to the difficult social reality in this historical period. Subjected to innumerable contradicitons, multiple identities, an undefinable self, not identifiable by absolutes, she certainly has the right to sally forth on the public scene.

Isa Blagden è brevemente ricordata nel Modern English Biography, che elenca le sue opere, presentandocela però soprattutto come “amica” di autrici ritenute più importanti di lei quali Elizabeth Barrett Browning e Theodosia Trollope. L’aver conosciuto e l’essere stata la confidente di personalità tutt’oggi ritenute tra le più significative del secolo diciannovesimo è stato al contempo la fortuna e la sfortuna di Blagden. Ha infatti ottenuto una sorta di immortalità indiretta nel ricordo dei posteri: era l’amica di Elizabeth Barrett Browning, con la quale condivideva le idee politiche e la passione per le pratiche spiritiche; era la confidente dello sconsolato Robert Browning, che dopo essere ritornato in Inghilterra in seguito alla morte della moglie mantenne con Isabella un rapporto epistolare conclusosi solo con la scomparsa della scrittrice.

Isa Blagden is briefly noted in Modern English Biography which lists her works, presenting her though as 'friend' of authors, among them, considering as more important, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Theodosia Trollope. To have known her and to have had her as confidente today would be held among the most significant personalities of the nineteenth century was both the fortune and misfortune of Blagden. She has in fact obtained a sort of oblique immortality in the memory of the past: she was Elizabeth Barrett Browning's friend, with whom she shared political ideas and the passion for spiritualist practices; she was the confidente of the unconsolable Robert Browning, who after returning to England following the death of his wife maintained an epistolary correspondence with Isabella which only ended with the death of that writer.

Sebbene Blagden “viva” soprattutto all’ombra dei Browning, essa viene ricordata anche nelle opere che trattano di altri scrittori o scrittrici che abitarono o solo visitarono il capoluogo toscano, visto che era improbabile per gli artisti angloamericani soggiornare a Firenze senza conoscere e rimanere affascinati da questa donna dall’animo gentile, che riceveva i suoi numerosi ospiti nelle ville di Bellosguardo. Ma questo suo aspetto di “amica universale” ha messo in ombra altri lati della sua personalità, e soprattutto il fatto che non solo amava circondarsi di artisti e letterati, ma che era essa stessa scrittrice. Romanziera e poetessa, viene abbandonata dopo aver affermato che era autrice mediocre e poco originale, poiché scriveva seguendo i canoni vittoriani. Di lei si recupera la personalità, tanto affascinante da attrarre intorno a sé gli artisti più importanti del periodo, trascurando le opere. Si dimentica che i romanzi e le poesie di Blagden sono l’unica fonte diretta da cui traspare l’identità dell’autrice e grazie alla penna riusciva a condurre una vita assai agiata, seppur nell’“economica” Bellosguardo.

Even when alive Blagden was always under the shadow of Browning, she became remembered even in the works on other writers who lived or who only visitied the Tuscan capital, seeing that it was unlikely that Anglo-American artists would stay in Florence without coming to know and to remain drawn to this gentle-souled woman, who received numerous guests in her villas at Bellosguardo. But this aspect of 'universal friend' has placed other sides of her personality in the shadows, and above all the fact that not did she love to surround herself with artists and writers, but that she was herself a writer. Novelist and poet, she is dropped after it is said she was a mediocre and scarcely original writer, because she wrote according to the Victorian canon. From her we can recover her personality, always drawn to attract around her the most important artists of the period, obscuring her work. We forget that Blagden's novels and poems are the one direct source from which can come the identity of the author and who thanks to the pen succeeded in leading a very well-to-do life, even if in the 'economical' Bellosguardo.

La caratteristica più singolare di Isabella Blagden è la scarsità di informazioni che si hanno sulla sua vita, in particolar modo per il periodo che va dalla sua nascita alla scelta di stabilirsi in Italia. La scrittrice non ha lasciato né autobiografie né diari, e anche nelle opere autobiografiche dei suoi amici più intimi non vi sono informazioni su di lei risalienti al periodo antecedente al 1849. Fra l’altro, la maggior parte delle lettere che ella scriveva regolarmente ai suoi numerosi amici sono andate perdute.

The most outstanding characteristic of Isabella Blagden is the lack of information that we have about her life, in particular for the period from her birth to her choice to settle in Italy. The writer left neither autobiography nor diary, and in even the autobiographical works of her most intimate friends there is no information on the period before 1849. Besides, the greater part of the letters that she regularly wrote to her numerous friends have been lost.

In mancanza di materiale diretto, le fonti fondamentali per avere notizie biografiche riguardanti Blagden sono l’introduzione al suo volume di versi dovuta al poeta laureato Alfred Austin, conosciuto da Blagden a Firenze nel 1865, e le lettere spedite mensilmente dal caro amico Robert Browning, conservate da Isa con cura e fortunatamente giunte fino a noi.

Lacking primary documentation, the fundamental sources for biographical information concerning Blagden are the introduction to her volume of poetry written by the Poet Laureate Alfred Austin, Blagden's friend in Florence in 1865, and the letters sent every month by her dear friend Robert Browning, kept by Isa with care and which fortunately have come down to us.

Le origini di Blagden appaiono avvolte nel più fitto mistero. Sebbene sia circondata da una folta schiera di amici, non vi è traccia di alcun legame familiare. Non sappiamo neppure con esattezza la data della sua nascita. Il registro del cimitero degli inglesi di Firenze, dove la scrittrice è sepolta, afferma che il nome del padre era Thomas e che Isa morì il 23 gennaio del 1873 a cinquantacinque anni. Tuttavia le date sulla sua tomba sono 1816–1873. In What I Remember Thomas Adolphus Trollope, nato nel 1810, ci dice che Blagden era molto più giovane di lui1 e ciò potrebbe far pensare al 1818, ma questa, naturalmente, è solo una supposizione, tanto più che i critici a tal proposito si dividono.2

Blagden's origins seem wrapped up in a most obscure mystery. Though surrounded by a full crowd of friends, there is not a trace of any family relation. We do not even know with any exactitude the date of her birth. The English Cemetery's Register in Florence, where the writer is buried, affirm that her father's name was Thomas and that Isa died 23 January 1873 at 55. Though the dates on her tomb are 1816-1873. In What I Remember, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, born in 1810, tells us that Blagden was much younger than he and this makes us think of 1818, but this, naturally, is only a supposition, so much are critics divided on the issue.

Nathaniel Hawthorne nel suo The Marble Faun,3 parlando di una delle protagoniste del romanzo, ha scritto parole che si adattano perfettamente alla situazione di Blagden, con l’unica differenza che l’eroina di Hawthorne è pittrice, anziché scrittrice. Parla di una certa “ambiguità”, che non implicava necessariamente niente di sbagliato; nessuno sapeva niente di lei, aveva fatto la sua apparizione senza introduzione.

Nathaniel Hawthorne in his Marble Faun, speaking of one of the romance's protagonists, has written words that apply perfectly to Blagden's situation, with the one difference that Hawthorne's heroine is a painter, rather than a writer. He speaks of a certain 'ambiguity' which does not necessarily imply anything wrongful; no one knew anything about her, since she made her appearance without an introduction.

Le origini di Blagden dovevano essere ignote anche a molti (se non tutti) suoi amici. Correva voce che le scorresse nelle vene sangue indiano. Lilian Whiting4 afferma che essa era la figlia di un gentiluomo inglese e una principessa Hindu. Le origini indiane di Blagden sembrano essere confermate dalle descrizioni fisiche che di lei riportano i suoi contemporanei. Kate Field e Margaret Jackson5 parlano di una donna di piccola statura, con occhi e capelli neri e carnagione olivastra; Henry James, che la conobbe brevemente durante uno dei suoi primi viaggi a Firenze, ricorda una sua passeggiata mattutina dal centro della città a Bellosguardo durante la quale parla con una piccola ed energica signora con occhi scuri e dall’aspetto vagamente indiano.6

Blagden's origins were unknown even to most (if not all) her friends. Rumour had it that in her veins ran Indian blood. Lilian Whiting affirms that she was the daughter of an English gentleman and a Hindu princess. Blagden's Indian origins seem to be confirmed by the physical descriptions given of her by her contemporaries. Kate Field and Margaret Jackson speak of a woman of small stature, with black eyes and hair and an olive complexion; Henry James, who knew her briefly during one of his first visits to Florence, writes of a morning walk from the centre of the city to Bellosguardo during which he spoke with a little and energetic lady with dark eyes and a vaguely Indian aspect.

E’ degno di nota il fatto che una donna come Isabella Blagden, il cui passato è avvolto nel mistero, abbia scelto come patria di adozione l’Italia, ed in particolar modo la tollerante Firenze, universalmente nota anche per il suo accogliere gli ospiti più “stravaganti”.

It is worthwhile noting the fact that a lady like Isabella Blagden, whose past is wrapped in mystery, had chosen Italy for her country of adoption, and in particular the tolerance of Florence, universally noted also for its acceptance of the most 'extravagant' guests.

I viaggi che significavano lunghi soggiorni fornivano l’opportunità di assumere atteggiamenti e ruoli che a casa sarebbero stati proibiti o impossibili. L’Italia era il luogo delle possibilità, il luogo dell’eccesso dove un altro io viveva la vita. L’Italia era il luogo dove l’amore tra Elizabeth e Robert Browning era possibile, dove persone altrove definite eccentriche venivano ricercate e stimate; si pensi a Walter Savage Landor, di cui sono leggendari gli scoppi di collera o Seymour Kirkup, pittore e collezionista d’arte, fanatico sostenitore dello spiritismo e conosciuto tra i connazionali come lo “stregone”.

The travels which meant long stays gave the opportunity to assume manners and roles that at home would have been forbidden or impossible. Italy was the place of opportunity, the place of excess where another self lived life. Italy was the place where the love between Elizabeth and Robert Browning was possible, where persons elsewhere considered eccentric came to be sought out and admired; one thinks of Walter Savage Landor, of whom there are legends about his great anger, or Seymour Kirkup, painter and art collector, fanatic supporter of spiritualism and known amongst his compatriots as the 'wizard'.

L’Italia, dunque, veniva a significare il luogo delle possibilità per le donne: allentate le maglie dell’identità, potevano vivere più liberamente secondo i propri desideri. Ecco allora che artiste come Harriet Hosmer, Louisa Lander, entrambe scultrici, Charlotte Cushmann, attrice, o anche donne immaginarie come Agnes Tremorne, protagonista dell’omonimo romanzo di Isa Blagden, ambientato a Roma, potevano permettersi di girare per le città da sole senza protezione maschile, ritenuta quasi “obbligatoria” nella madrepatria.

Italy, then, came to mean a place of opportunity for women: loosening the garb of their identity they could live more freely according to their own desires. This was so with artists like Harriet Hosmer, Louisa Lander, both of them sculptresses, Charlotte Cushmann, actress, and also imaginary women like Agnes Tremorne, protagonist of the novel of the same name by Isa Blagden, set in Rome, who could permit themselves to go about the cities alone without masculine protection, considered almost obligatory in their motherland.

Viene da domandarsi poi, se Isa Blagden, donna non sposata che viveva da sola o condividendo la villa del momento con altre donne nubili, sarebbe stata egualmente da tutti ricordata ed elogiata se avesse intrattenuto i suoi ospiti in qualche salotto vittoriano invece che sulla terrazza di villa Brichieri-Colombi. In Italia Isa poteva permettersi di non rilevare le sue origini e di scegliersi così l’identità che preferiva.

One can ask whether Isa Blagden, unmarried woman living alone or sharing her villa at times with other unmarried women, would have been equally remembered and praised by all if she had welcomed guests in some English Victorian salon instead of on the terrace of the Villa Brichieri-Colombi. In Italy Isa could permit herself to not disclose her origins and to choose thus the identity she prefered.

La vita fiorentina di Blagden iniziò, come testimonia Alfred Austin,7 nell’introduzione alle poesie di Blagden apparse postume nel 1873, nel 1849 e in questa città rimase fino alla morte, anche se, seguendo le abitudini degli angloamericani, trascorse lunghi periodi in altri parti d’Italia o all’estero. La città toscana si trasformò per lei in patria d’adozione, divenne il luogo fisso dove fare ritorno alla fine di ogni viaggio. Sebbene all’inizio del suo soggiorno Blagden occupasse Villa Moutier, un’abitazione vicino a Poggio Imperiale, a circa un chilometro di distanza da Porta Romana, la scrittrice si innamorò di un luogo particolare di Firenze: quella località situata sulla riva sinistra dell’Arno denominata Bellosguardo, che divenne nel corso dell’Ottocento una sorta di “isola” angloamericana. Se Bellosguardo ebbe mai una regina, questa fu sicuramente Isabella Blagden, che trascorse gran parte dei suoi ventiquattro anni italiani su questa collina, cambiando più volte dimora, ma scegliendo sempre ville che si trovavano a pochi passi l’una dall’altra e addirittura invitando i suoi amici più cari (come Austin e gli Hawthorne) a seguire il suo esempio e a stabilirsi sul “colle delle grazie”.8 Non a caso Kate Field, in un articolo intitolato English Authors in Florence, non chiama Blagden col suo nome e preferisce definirla “our Lady of Bellosguardo”. Field era consapevole che qualsiasi angloamericano che fosse anche solo passato per Firenze, avrebbe riconosciuto nella “little lady with blue black hair and sparkling jet eyes”9 la scrittrice inglese.

Blagden's Florentine life began, as Alfred Austin notes, in his introduction to Blagden's Poems published posthumously in 1873, in 1849 and she remained in this city until her death, even if, following the habits of the Anglo-Americans, she spent long periods in other parts of Italy or abroad. The Tuscan city became for her her adopted country, becoming the fixed abode to which she would return after each journey. Although at the beginning of her stay Blagden lodged at Villa Moutier, a place near Poggio Imperiale, about a kilometre from Porta Romana, the writer came to love a particular part of Florence: that locality situated on the left of the Arno called Bellosguardo, that became in the course of the nineteenth century a sort of Anglo-American 'island'. If Bellosguardo ever were to have a queen, she would have certainly been Isabella Blagden, who spent the great part of her twenty four years in Italy on this hill, changing her dwelling place often, but always choosing villas which were found a few steps from each other and even inviting her most dear friends (such as Austin and the Hawthornes) to follow her example and to settle on this 'gracious hill'. Not by chance Kate Field, in an article entitled 'English Authors in Florence', calls Isa Blagden not by her name prefering to name her 'Our Lady of Bellosguardo'. Field was aware that any Anglo-Americans who were only passing through Florence, would have recognized in the 'little lady with blue black hair and sparkling jet eyes' the English writer.

Tre sono le ville di Bellosguardo maggiormente associate con Blagden: villa Brichieri-Colombi, villa Giglioni, e villa Castellani, sebbene essa abbia abitato brevemente in un altro edificio situato sul colle, la villa Isetta.

Bellosguardo

Bellosguardo

Da Alta Macadam, Americans in Florence: A Complete Guide to the City and Places Associated with Americans Past and Present, Florence: Giunti, 2003.

There are three villas in Bellosguardo most associated with Blagden: Villa Brichieri-Colombi, Villa Giglioni and Villa Castellani, although she lived briefly in another house on the hill, Villa Isetta.

Come ho già detto, da un punto di vista economico la scrittrice aveva non poche difficoltà: disponeva di mezzi modesti e si guadagnava da vivere soprattutto grazie alla scrittura. Una delle ragioni per cui elle visse così a lungo a Bellosgurado è appunto la relativa conomicità del luogo rispetto ad altre zone di Firenze. La povertà e quindi la necessità di alleggerire le spese domestiche, era anche la giustificazione che Blangen indicava per condividere l’appartamento con altre donne. Nel corso del 1860 Blagden divise villa Brichieri –Colombi con Frances Power Cobbe, che illustrò nella sua autobiografia il lato finanziario della vita a Bellosguardo.

As already said, from the economic point of view the writer had not a few problems: she had modest means and earned her living above all from her writing. One of the reasons why she lived for so long at Bellosguardo is precisely because of the relative economy of the place in comparision with other parts of Florence. Her poverty and therefore the necessity to save on domestic costs, was also the justification that Blagden gave for sharing her apartment with other women. In the course of 1860 Blagden shared Villa Brichieri-Colombi with Frances Power Cobbe, who illustrated in her autobiography the financial side of life at Bellosguardo.

Cobbe non è l’unica persona con cui Blagden ha condiviso l’appartamento, quella di dividere le spese con un’altra donna era una vera e propria consuetudine per la scrittrice. Tra quest’ultima e le sue “ospiti paganti” si veniva a creare un rapporto basato su una profonda amicizia, la quale durava ben oltre il periodo di convivenza.

Cobbe was not the only person with whom Blagden had shared her apartment, sharing expenses with another woman was a true and proper custom for the writer. Between this last and her 'paying guests' she came to create a relationship based on deep friendship, which lasted beyond their time of living together.

In tutti i romanzi di Blagden l’amicizia, la solidarietà e la convivenza tra donne è esaltata in continuazione. Alla luce di ciò che la scrittrice propone nei suoi testi, la sua posizione di donna nubile che condivideva le sue abitudini con varie amiche assume tutta l’importanza di una decisione autonoma che in qualche modo si contrapponeva alle regole della società, secondo le quali ogni “zitella” era infelice a causa del suo stato civile, dovuto a cause di forza maggiore e non ad una libera scelta.

In all Blagden's novels friendship, solidarity and the living together of women was continuously praised. In the light of what the writer promoted in her texts, her position as a single woman who shared her life with various friends assumes all the importance of an autonomous decision which in someways contrasted with social rules, according to which each 'spinster' would be unhappy because of her civil state, due to force majeure and not a free choice.

Blagden divise i suoi appartamenti sia con letterate e artiste, i cui nomi sono ancora conosciuti e apprezzati, sia con donne che non si dedicavano all’arte, oggi del tutto dimenticate. Dalla corrispondenza tra Elizabeth Barrett Browning e Blagden si deduce che intorno alla metà del secolo l’autrice di Agnes Tremorne condivideva l’appartamento con una certa Miss Agassiz. Se ne ha conferma da una lettera datata 1850 circa in cui la poetessa invita Blagden e Agassiz a casa Guidi, e da un’altra del maggio del 1851, in cui Browning chiede notizie sulla salute di Agassiz.10 Nel 1852, di ritorno da una visita in Inghilterra, Blagden portò con se Louisa Alexander, una donna invalida di cui la scrittrice si prese cura e che visse con lei fino al giugno del 1855, quando Alexander partì per l’India. Blagden instaurò un rapporto di grande amicizia con questa donna e la sua morte, avvenuta nel 1858, la rattristò molto. Sia Elizabeth sia Robert Browning, che quell’inverno risiedevano a Parigi, le scrissero lunghe lettere di consolazione, consapevoli del dolore che questa perdita aveva provocato.11

Blagden shared her apartments both with writers and artists, whose names are still known and appreciated, and with women not dedicated to art, today all forgotten. From the correspondence between Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Blagden one can deduce that around mid-century the author of Agnes Tremorne shared the apartment with a certain Miss Agassiz. This is confirmed in a letter dated about 1850 in the poetess invites Blagden and Agassiz to Casa Guidi, and by another of May 1851, in which Browning asks about Agassiz's health. In 1852, returning from a visit to England, Blagden brought with her Louisa Alexander, an invalid whom she looked after and who lived with her until June 1855, when Alexander left for India. Blagden established a great friendship with this woman whose death, which came about in 1858, left her very sad. Both Elizabeth and Rober Browning, who that winter were residing in Paris, wrote to her long consoling letters, being aware of the sorrow this loss provoked.

In data 27 giugno 1858, Hawthorne ci parla nel suo diario di viaggio di una giovane compagna che divideva Villa Brichieri Colombi con Blagden.12 “Dal 1857 al 1858 infatti Blagden divise il suo appartamento con Annette Bracken, una giovane inglese di ventiquattro anni.13In una lettera alla cognata, Barrett Browning14 illustrava i termini dell’accordo tra le due donne. Bracken aveva a sua completa disposizione una camera e un salotto di villa Brichieri-Colombi, e pagava anche una quota per la carrozza. “Annette” venne ben accolta dagli amici di Blagden che si riunivano regolarmente sul balcone di villa Brichieri-Colombi; accompagnava la padrona di casa durante le sue visite agli angloamericani residenti a Firenze15 e seguiva l’amica più anziana anche durante le vacanze estive. Nell’agosto del 1857 le due donne visitarono assieme Bagni di Lucca, dove incontrarono altri angloamericani, (tra cui i Browning e il poeta Robert Lytton) che avevano abbandonato la torrida Firenze per rifugiarsi sulle fresche colline lucchesi.

Hawthorne in his travel diary for 27 June 1858 spoke of a young companion who shared Villa Brichieri-Colombi with Blagden. From 1857 to 1858, in fact, Blagden shared her apartment with Annette Bracken, a young Englishwoman of 24. In a letter to her sister-in-law, Barrett Browning described the arrangement between the two women. Bracken had at her complete disposition a bedroom and a sitting room in the Villa Brichieri-Colombi and paid even a share for the carriage. 'Annette' was welcomed amongst Blagden's friends who came together regularly on the balcony of the Villa Brichieri-Colombi; accompanying her landlandy during her visits to the Anglo-Americans residing in Florence and followed the older friend also on her summer holiday. In August of 1857 the two women went together to Bagni di Lucca, where they met other Anglo-Americans (among them the Brownings and the poet Robert Lytton) who had left torrid Florence for a refuge amongst the cool hills of Lucca.

Un’ altra coinquilina di Blagden in questo periodo fu Kate Field. Arrivò in Italia all’inizio del 1859 accompagnata dagli zii, i signori Sanford. Field, che successivamente diverrà una giornalista di grande talento e fama, era allora una giovane di vent’anni, felice di realizzare un suo sogno: quello di venire nella penisola a studiare musica. Dopo un breve periodo trascorso a Roma, Field giunse a Firenze. Grazie ad alcune lettere di presentazione indirizzate ai Browning, ai Trollope e agli Hawthorne, che Field aveva ricevuto dal direttore del Boston Courier, il Signor Launt, riuscì ben presto ad inserirsi nell’ambiente culturale anglofiorentino. Alla partenza degli zii, Field volle trattenersi nella città toscana e fu, come afferma Whiting “placed in the care of Miss Blagden.”16 Quest’ultima portava con se Kate Field ovunque si recasse. Ad esempio, nel settembre del 1859 Blagden fu invitata dai Browning che stavano trascorrendo i mesi estivi nella campagna senese e vi si recò assieme alla giovane amica.17 A villa Brichieri-Colombi Kate Field rimase fino ai primi mesi del 1860, quando la signora Field raggiunse Kate a Firenze. Tuttavia, anche dopo che madre e figlia si furono trasferite in un appartamento in città continuarono a frequentare assiduamente Bellosguardo, dove si recavano quasi ogni giorno. L’amicizia tra Blagden e Field non cessò nemmeno quando quest’ultima fece ritorno in America.

Kate Field, from Lilian Whiting, Jeannette Marks

Another house guest for Blagden during this period was Kate Field. Arriving in Italy at the beginning of 1859 accompagnied by her Sanford aunt and uncle. Field, who later become a journalist of great talent and fame, was then a young woman of 20, happy to realize her dream: that of living in Italy and studying music. After a brief period at Rome, Field came to Florence. Thanks to some letters of presentation directed to the Brownings, to the Trollopes and to the Hawthornes, that Field had received from the director of the Boston Courier, Mr Launt, she quickly succeeded in fitting into the Anglo-Florentine cultural milieu. When her relatives left, Field wanted to stay in the Tuscan city and was, as Whiting affirms, 'placed in the care of Miss Blagden'. This last took Kate Field with her wherever she went. For example, in September 1859 Blagden was invited by the Brownings who were spending some months in the Sienese countryside and she went there with her young friend. Kate Field stayed at Villa Brichieri-Colombi until the first months of 1860, when Mrs Field joined Kate at Florence. However, even after the mother and daughter moved to an apartment in the city they continued to frequent Bellosguardo assiduously, where they went almost daily. The friendship between Blagden and Field never ceased, not even when this last made her return to America.

Quando Kate Field, all’inizio del suo soggiorno italiano, era giunta a Roma, aveva fatto la conoscenza di tre donne, anch’esse legate a Blagden da una profonda amicizia: l’attrice Charlotte Cushman, e le scultrici Harriet Hosmer e Emma Stebbins. All’inizio del 1859, quando le incontrò, esse condividevano (da pochi giorni) una casa al numero 38 di via Gregoriana. L’edificio, grazie alla presenza di queste grandi artiste, divenne uno dei luoghi di incontro di Roma più frequentati dagli anglo-americani. Le tre donne erano legate dalla comune amicizia per Isabella Blagden; tutte e tre furono ospiti a Bellosguardo. Durante il loro periodo italiano, soggiornavano di preferenza a Roma e quando visitavano il capoluogo toscano venivano accolte da Isa Blagden. Talvolta l’ospitalità veniva ricambiata e la scrittrice si recava a Roma dalle tre amiche.

When Kate Field, at the beginning of her Italian sojourn, came to Rome, she had made the acquaintance of three women, also tied to Blagden with a deep friendship: the actress Charlotte Cushman, and the sculptresses Harriet Hosmer and Emma Stebbins. At the beginning of 1859, when she met them they were sharing (from a few days before) a house at number 38, Via Gregoriana. The building, thanks to the presence of these great artists became one of the meeting places in Rome most frequented by the Anglo-Americans. The three women were tied by common friendship to Isabella Blagden; all three had been guests at Bellosguardo. During the long Italian period, staying by preference in Rome and when visiting the Tuscan capital they were welcomed by Isa Blagden. Sometimes the hospitality came to be reciprocated and the writer would come to the Rome of her three friends.

L’ospitalità di Blagden non si riduceva, come abbiamo visto, nell’accogliere e dividere la propria casa con altre donne. Durante gli anni che vanno dal 1856 al 1861 Isabella Blagden consacrò principalmente il suo tempo e la sua energia alla vita sociale. Questo fu il periodo in cui la scrittrice abitò a villa Brichieri-Colombi, dimora che divenne il luogo di ritrovo per eccellenza.

Blagden's hospitality was not limited, as we have seen, to the welcoming and sharing of her own house with other women. During the years from 1856 to 1861 Isabella Blagden principally dedicated her time and energy to social life. This was the period in which the writer lived at Villa Brichieri-Colombi, the dwelling which became the meeting place par excellence.

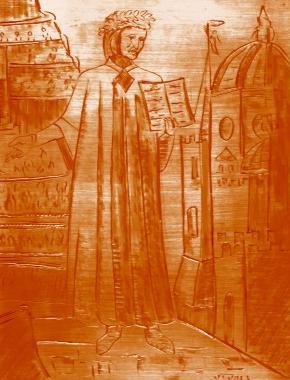

John Brett, Florence from Villa Brichieri,

Bellosguardo, 1863, painted after reading Aurora Leigh

Hebrew Cemetery on left outside

wall.

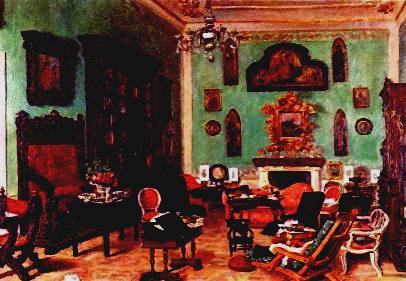

Frances Power Cobbe ricorda nella sua autobiografia che sul balcone di villa Brichieri-Colombi si ritrovavano regolarmente una compagnia interessante e molteplice.18 Blagden riceveva nelle sue ville di Bellosguardo numerosi ospiti di diverse nazionalità; sebbene i ricevimenti veri e propri si tenessero una volta alla settimana (il sabato), gli amici più intimi si recavano alla villa quasi ogni giorno. Nei salotti di Blagden si ritrovavano sia gli angloamericani stabilitisi a Firenze, sia coloro che si trovavano nella città toscana anche solo per un breve periodo. Alfred Austin ci ricorda come Blagden amasse circondarsi di “truly congenial spirits” e come fosse molto raro che un letterato o un artista passasse per Firenze senza fare la sua conoscenza.19

Frances Power Cobbe recalls in her autobiography that one regularly found an interesting and varied company on the balcony of the Villa Brichieri-Colombi. Blagden received in her Bellosguardo villas numerous guests of different nationalities; although the true and proper receptions were only once a week (on Saturdays), her intimate friends were received at the villa amost every day. In Blagden's drawing rooms one would meet Anglo-Americans resident in Florence, and those who came to theTuscan city for only a brief period. Alfred Austin notes how Blagden loved to have around herself 'truly congenial spirits' and how it would be rare for a writer or artist passing through Florence not to make her acquaintance.

Cobbe, che si vantava delle personalità che aveva avuto occasione di incontrare a villa Brichieri-Colombi, ha anche elencato i nomi dei vari ospiti che più frequentemente lei e Blagden ricevevano durante quella primavera del 1860.20 Dopo aver ricordato tra gli amici più intimi di Blagden, i Browning, specificando che dato le precarie condizioni di salute della moglie, solo Robert frequentava abitualmente villa Brichieri-Colombi, Cobbe parla di Thomas Adolphus Trollope come di un altro assiduo ospite del salotto di Bellosguardo.21

Cobbe, who boasted of the personalities she had had the occasion of meeting at Villa Brichieri-Colombi, has also listed the names of the various guests whom she and Blagden most frequently received during the Spring of 1860. After having noted among the most intimate of Blagden's friends, the Brownings, specifying that due to the precarious state of health of his wife, only Robert habitually frequented Villa Brichier-Colombi, Cobbe speaks of Thomas Adolphus Trollope as another frequent guest to Bellosguardo's salon.

Cobbe cita inoltre Linda White, la scrittrice, autrice tra l’altro di Tuscan Hills and Venetian Waters, che successivamente sposò lo storico Pasquale Villari. Essa fu l’unica dei numerosi conoscenti di Blagden a essere presente durante la sua ultima malattia. Frequentatore assiduo di Belloguardo era anche Walter Savage Landor, di cui Blagden fu una delle persone più vicine durante gli ultimi anni della sua vita. Fino a quando Robert Browning era rimasto a Firenze si era occupato di lui, gli aveva persino trovato un alloggio quando, in seguito ad un litigio, la moglie lo aveva cacciato da villa Gherardesca a Fiesole;22 dopo che Browning lasciò la Toscana, Blagden si prese cura di Landor andando spesso a fargli visita fino alla morte, avvenuta nel settembre del 1864. Cobbe ricorda inoltre tra i loro ospiti abituali il dottor Grisanowski, di nazionalità polacca, Jessie White Mario e Frederick Tennyson, il poeta e musicista che aveva precedentemente soggiornato a Bellosguardo, proprio nella villa Brichieri-Colombi.

Cobbe also mentions Linda White, the writer, author among other books of Tuscan Hills and Venetian Waters, who later married the historican Pasquale Villari. She was only one of the many acquaintances of Blagden to be present during her last illness. A frequent visitor at Bellosguardo was also Walter Savage Landor, Blagden being one the people closest to him duirng the last years of his life. As long as Robert Browning remained in Florence he took care of him, having already found him a lodging, when, following an argument, his wife had chased him out of the Villa Gherardesca at Fiesole; after Browning left Tuscany, Blagden cared for Landor going often to visit him until his death in September 1864. Cobbe notes also among the usual guests the doctor Grisanowski, who was Polish, Jessie White Mario and Frederick Tennyson, the poet and musician who had previously stayed at Bellosguardo, indeed at the Villa Brichieri-Colombi itself.

Nel 1860 erano inoltre presenti a Firenze l’americana Harriet Beecher Stowe, autrice di Uncle Tom’s Cabin, che frequentò il salotto di Bellosguardo, e George Eliot. Quest’ultima non si recò mai a villa Brichieri, tuttavia Blagden ebbe occasione di conoscerla quando questa si trovava a Villino Trollope e “was enchanted, like all the world, with [her].”23

In 1860 there was also present in Florence the American Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, who frequented the salon at Bellosguardo, and George Eliot. This last never went to Villa Brichieri, however Blagden had the occasion to know her when she went to Villino Trollope and 'was enchanted, like all the world, with her'.

Cobbe tralascia, per dimenticanza o perché assenti da Firenze nel 1860, alcune personalità che frequentarono assiduamente il salotto di Blagden e con le quali la scrittrice instaurò durature amicizie: tra questi Nathaniel e Sophia Hawthorne, che soggiornarono a Firenze nel 1858, lo scultore americano Hiram Powers, il musicista Francis Boott, che abitava a Bellosguardo, in un appartamento di villa Castellani, Anna Jameson, la storica dell’arte e una delle più care amiche di Barrett Browning, Robert Lytton, il poeta che scriveva utilizzando lo pseudonimo di Owen Meredith e che aveva soggiornato a villa Brichieri-Colombi nei primi anni Cinquanta.

Cobbe omitted, from forgetfulness or because they were absent from Florence in 1860, other personalities who were frequent visitors at Blagdon's salon and and with whom the writer established a lasting friendship: among these Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne who stayed in Florence in 1858, the American sculptor Hiram Powers, the musician Francis Boott, who lived at Bellosguardo, in an apartment in the Villa Castellani, Anna Jameson, the art historian and one of the dearest friends of Barrett Browning, Robert Lytton, the poet who wrote using the pseudonym of Owen Meredith and who had lived at the Villa Brichieri-Colombi in the beginning of the 1850s.

Con questo elenco non intendo certo esaurire il numero delle persone che frequentavano il salotto di Blagden a Bellosguardo. Alfred Austin a proposito delle amicizie della scrittrice parla di “the widest circle of friends I have ever heard of one person possessing” e successivamente la definisce “a universal favourite”.24Sarebbe quindi quasi impossibile citare tutti i suoi conoscenti.

With this list we have certainly not exhausted the number of people who frequented Blagden's salon at Bellosguardo. Alfred Austen concerning the writer's friendships spoke of 'the widest circle of friends I have heard of one person possessing' and later defined her 'a universal favourite'. It would be almost impossible to give all her acquaintances.

Blagden era la protagonista principale di questi incontri, sebbene non fosse in alcun modo quella che veniva definita una “grande dame”. La sua conversazione era animata e gaia, sebbene di carattere non fosse particolarmente estroversa ed espansiva, non possedeva cioè quelle qualità che qualche anno prima avevano permesso alla brillante Contessa Blessington di dominare nel suo elegante salotto situato sul Lung’Arno. Uno degli attributi di Isabella Blagden che più colpiva i suoi amici era l’umiltà, caratteristica che poco si accorda con la comune concezione della figura della salonnière, di solito una donna di temperamento esuberante, abituata ad essere al centro dell’attenzione. Ma Blagden, pur nella sua pacatezza, riusciva ad intrattenere e divertire i suoi numerosi ospiti che spesso erano caratterialmente diversissimi tra loro. A questo proposito Austin ci dice che niente rendeva così contenta Blagden come l’ospitare nella sua villa i suoi amici, ma la sua benevolenza era così grande che spesso ella commetteva l’errore di mescolare l’acqua con il fuoco. “Yet she herself possessed some secret charm, which enabled her to fuse equally with either.”25 Lilian Whiting, nel suo The Florence of Landor, ha scritto riferendosi ai membri che facevano parte della colonia angloamericana: “the many strong and altogether dissimilar individualities that composed this cercle entime all found some point of common meeting with “Isa”, as they all called her.”26Per tutti basta ricordare che i rapporti che intercorrevano tra Robert Browning e Alfred Austin, due dei migliori amici Blagden, erano tutt’altro che amichevoli.27

Blagden was the principle protagonist in these encounters, although she was not in any way like what came to be defined as a 'grand dame'. Her conversation was animated and gay, although not of a particularly extroverted or expansive character, not possessing that quality which had some years earlier permitted the brilliant Lady Blessington to dominate over her elegant salon situated on the Lung'Arno. One of Isabella Blagden's attributes that most struck her friends was her humility, a characteristic that little accords with the common conception of the figure of the salon leader, usually a woman of exuberant temperament, accustomed to being the centre of attention. But Blagden, even in her quietness, succeeded in pleasing and entertaining her numerous guests who often were in character very different from each other. About this, Austin tells us that nothing made Blagden so content as to host her friends in her villa, but her benevolence was so great that often she committed the error of mixing water and fire. 'Yet she herself possessed some secret charm, which enabled her to fuse equally with either'. Lilian Whiting, in her The Florence of Landor, has written refering to members who made part of the Anglo-American colony: 'the many strong and altogether dissimilar individualities that composed this cercle entime all found some point of common meeting with 'Isa', as they all called her.' It is enough to mention that the relationship between Robert Browning and Alfred Austin, two of Blagden's best friends, was far other than amicable.

Gli argomenti di cui si discuteva durante questi ricevimenti erano vari. Le discussioni vertevano su temi di arte, di musica e di letteratura, ma soprattutto di politica e di spiritismo, un argomento quest’ultimo che appassionava quasi tutti gli ospiti, eccezion fatta per qualche scettico come Walter Savage Landor e Robert Browning. Ma il tema di discussione più interessante era certamente la questione politica italiana.

The topics which they discussed during these receptions were varied. The discussions turned upon themes of art, of music and of literature, but above all of politics and spiritualism, this last argument about which almost all of the guests were passionate, exceptions being made for some sceptics like Walter Savage Landor and Robert Browning. But the most interesting discussion was certainly that of the Italian political question.

Nel periodo in cui Isabella Blagden visse a villa Brichieri-Colombi, le questioni dell’indipendenza e dell’unità nazionale dominavano il pensiero dell’opinione pubblica italiana. Gli anglofiorentini che si trovavano regolarmente sul terrazzo di Bellosguardo non potevano evitare di interessarsi all’Italia contemporanea: in effetti tra gli argomenti sovente affrontati vi erano i problemi politici e sociali della loro “seconda” patria.

In the period in which Isabella Blagden lived in the Villa Brichieri-Colombi, the questions of independenze and of national unity dominated the thinking of Italian public opinion. The Anglo-Florentines who were regularly to be found on the terrace of Bellosguardo could not but be interested in contemporary Italy: indeed among the arguments often brought up were those of the political and social problems of their 'second' country.

Esistevano opinioni profondamente diverse all’interno del gruppo e non raramente accadeva che anche in un singolo individuo si configurassero opinioni complesse e anche contraddittorie. Si configurava una conflittualità tra il persistere di un certo conformismo che si adeguava all’ideologia vittoriana e l’apertura verso modi di pensare nuovi. Gli anglofiorentini erano tutti a favore a favore dell’unità d’Italia, ma erano intimoriti dal fatto che promuovendo l’unità della penisola non si sapeva bene a che tipo di governo si andasse incontro e avevano paura che la loro serenità venisse in qualche modo turbata. Se messi a confronto con i connazionali che non avevano lasciato la patria, gli anglofiorentini apparivano più aperti a riconoscere l’esistenza di altri mondi oltre quello britannico; essi si impegnarono in lotte politiche che non gli “appartenevano”, mantenendo però un atteggiamento conservatore e di rifiuto verso qualsiasi sconvolgimento sociale che avrebbe potuto turbare la tranquillità della loro vita fiorentina.

There were profound differences within the group and it sometimes happened that even in a single individual there would be complex and even contradictory opinions. There was a conflict between a certain obstinate conformism which adapted to the Victorian ideology and the opening toward new modes of thought. The Anglo-Florentines were all in favour of the Unity of Italy, but were timid about it at the same time because in promoting the unity of the peninsula they would not know what type of government they would meet with and were afraid that their serenity would be in some way disturbed. In comparision with their compatriots who had not left England, the Anglo-Florentines seemed more open to recognising the existence of other worlds than the British one; they engaged in political struggles which did not belong to them, maintaining, however, a conservative and negative attitude towards whatever social turmoil that could have disturbed the tranquillity of their Florentine life.

Se analizziamo i rapporti che concretamente venivano a instaurarsi tra angloamericani e italiani, ci troviamo di fronte a un’incredibile assenza di contatti. Rimane la sensazione che la società inglese in Italia si presentasse come un circolo chiuso, nel quale si veniva a creare una realtà vicino a quella della madrepatria, che si credeva si fosse lasciata alle spalle.

If we analyse the relations that came about concretely between the Anglo-Americans and the Italians, we find before us an incredible absence of contact. The sensation remains that English society in Italy presented itself as a closed circle, in which was created a reality close to that of the motherland, which it believed had been left behind.

L’Italia, con i suoi problemi di unità, era un argomento centrale nelle loro discussioni, ma gli italiani che venivano ammessi a partecipare a queste riunioni erano pochissimi. Blagden non era certo un’eccezione. Fondamentalmente il suo punto di vista rimase sempre quello imperialista; nonostante la sua volontà ad aprirsi a nuove esperienze, di prendere in considerazione nuove realtà politiche diverse da quelle dell’Inghilterra. L’italiano fu sempre considerato da Blagden, come dalla maggioranza degli anglofiorentini, come “l’altro”, un individuo “diverso” e quindi inferiore.

Italy, with its problems of unity, was a central argument in their discussions, but the Italians who were admitted to participate in these gatherings were very few. Blagden was no exception. Fundamentally her point of view remained always imperial; notwithstanding her will to open herself to new expereinces, to take into consideration new and different political realities than those of England. The Italian was always considered by Blagden, as by the majority of the Anglo-Florentines, as the 'other', an individual 'different' than themselves and therefore inferior.

Gli unici italiani con cui Blagden e gli angloamericani in genere venivano in contatto appartenevano a classi sociali basse: i domestici, che venivano preferiti a quelli inglesi perché più economici, e i modelli di cui si servivano gli artisti, i quali possedevano quelle qualità “pittoresche” che gli angloamericani perennemente ricercavano. Se talvolta il rapporto tra i “signori” e i loro domestici andava al di là del semplice contatto lavorativo, i ruoli e le classi sociali rimanevano divisi in maniera netta. La convivenza dava luogo a un affetto che non intaccava la superiorità nazionale e di classe.

The only Italians with whom Blagden and the Anglo-Americans generally came into contact belonged to the lower social classes: the servants, who were prefered to the English because more economical, and the models who served the artists, those who possessed 'picturesque' qualities that the Anglo-Americans always sought. If sometimes the relationship between the 'Master' and the servant went beyond the mere work contact, the roles and the social classes remained decidedly divided. Shared living gave place to an affection that did not override national superiority or class.

Più o meno tutti coloro di cui ho parlato hanno descritto nei loro diari, nelle loro lettere o nelle loro autobiografie le piacevoli serate trascorse sul colle fiorentino e hanno ricordato con parole di stima e di affetto la padrona di casa. Dai resoconti che di lei hanno lasciato i suoi contemporanei traspare una donna intelligente e dalla vasta cultura, in grado di affrontare conversazioni su argomenti disparati. Ma gli aspetti della personalità di Blagden che più vengono evidenziati sono il suo altruismo e la sua generosità, che la rendevano, come afferma Trollope, “more universally beloved than any other individual among us”.28Anche Henry James, che ha dedicato qualche pagina del suo William Wetmore Story and His Friends all’amica di Bellosguardo, sottolinea l’altruismo di Blagden e parla di lei come di una piccola leggenda.29Inoltre, Austin scrive: “No matter what might be at the moment her own occupations, her own plans, or the demands of her own interest, she quitted them on the instant at the invitation of helplessness.”30 Il poeta, a conferma di quanto ha scritto, riporta anche un episodio che lo riguarda. Nel 1865 Blagden, sebbene fosse molto occupata per motivi personali, non negò il suo aiuto all’amico quando questi gli chiese di procurargli un alloggio a Firenze.

More or less all those who have written in their diaries, their letters, or their autobiographies were pleased to have crossed over to the Florentine hill and have remembered the lady of the house with admiration and affection. From the accounts about her that have come down to us from her c ontemporaries we are shown a lady of intelligence and of great culture, capable of fielding conversations on different arguments. But the aspects of Blagden's personality that are most in evidence are her altruism and her generosity, which render her, as Trollope affirmed, 'more universally beloved than any other individual among us'. Even Henry James, who had dedicated some pages of his William Wetmore Story and his Friends, to the friend of Bellosguardo, underlined Blagden's altruism and spoke of her as like a little legend. Also, Austin wrote: 'No matter what might be at the moment her own occupations, her own plans, or the demands of her own interest, she quitted them on the instant at the invitation of helplessness'. The poet, to confirm what he had written, reported another episode concerning her. In 1865 Blagden, although much occupied with personal troubles, did not refuse her help to her friend when he asked her to find him lodging in Florence.

Il suo altruismo è dimostrato dalla solerzia con cui aiutava gli amici che avevano bisogno di lei per motivi di salute. Nel 1857, durante un’estate a Bagni di Lucca, il poeta Robert Lytton si ammalò gravemente di febbri gastriche. Le lettere dei Browning, anche loro residenti sulle colline lucchesi, testimoniano con quanta cura Blagden si prendesse cura dell’amico. All’inizio si rifiutò persino di chiamare un’infermiera, ostinandosi a voler occuparsi da sola dell’ammalato. Quando il poeta iniziò a sentirsi meglio e fu in grado di muoversi da Bagni di Lucca, Blagden lo portò con se a villa Brichieri-Colombi, dove egli trascorse i giorni della sua convalescenza.

Her altruism is shown by thecare with which she helped her friends who had need of her for health reasons. In 1857, during a summer at Bagni di Lucca, the poet Robert Lytton became gravely ill with gastric fever. The Brownings' letters, they also being resident then in the hills above Lucca, witnessed to how much care Blagden took of their friend. At the beginning she refused to call for a nurse, obstinately wanting to take on the care alone of the invalid. When the poet began to feel better and was ready to move from Bagni di Lucca, Blagden took him with her to Villa Crichieri-Colombi, where he passed the days of his convalescence.

Alcuni critici, tra cui William Raymond e Giuliana Artom Treves, avanzano l’ipotesi di una sorta di relazione sentimentale che nacque in questo periodo tra Blagden e Lytton, amore che sembrerebbe incoraggiato dai Browning. Elizabeth Barrett Browning identificò Isa come la “Cordelia” della poesia di Lytton intitolata The Wanderer, e con questo nome la poetessa si rivolge all’amica in una lettera del 1859.31 William Raymond prende spunto da alcune parole della figlia di Lytton, Betty Balfour, la quale scrisse che appena giunto in Italia il padre incontrò una donna a cui si affezionò, ma a cui non si poté legare a causa di barriere insormontabili. Balfour aggiunse che comunque questo legame influenzò gran parte degli scritti giovanili del padre. Raymond individua le “barriere” per cui il matrimonio tra i due sarebbe stato impossibile (prima fra tutti i quindici anni di età che dividevano i due scrittori) e analizza una poesia giovanile di Lytton, Lucile, dove nell’eroina riscontra alcune caratteristiche che potrebbero adattarsi alla Blagden. Lucile è infatti un’euroasiatica, viene descritta come una donna matura e le caratteristiche fisiche corrisponderebbero a quelle della scrittrice anglofiorentina.32

Some critics, among them William Raymond and Giuliana Artom Treves, have advanced the hypothesis of a sort of romance that blossomed in this time between Blagden and Lytton, a love that seemed to be encouraged by the Brownings. Elizabeth Barrett Browning identified Isa with the 'Cordelia' of Lytton's poetry in The Wanderer, and with this name the poet turned to her friend in an 1859 letter. William Raymond took this from some words from Lytton's daughter, Betty Balfour, who wrote that just when her father reached Italy he met a woman whom he loved, but whom he could not marry because of insurmountble barriers. Raymond defined the 'barriers' for which marriage between the two would have been impossible (first there being fifteen years difference in age between the two writers) and analyzed Lytton's juvenile poetry, Lucile, where the heroine matches some characteristics that could be applied to Blagden. Lucile is in fact a Euro-Asian, described as a mature woman with with characteristic physical features which could correspond to those of the Anglo-Florentine writer.

Isabella Blagden comunque non riservò le sue cure come infermiera solo a Lytton. Nel 1865 assistette Theodosia Trollope nella sua ultima malattia e dopo la sua scomparsa si prese cura della figlia Beatrice, che ospitò a Bellosguardo nei giorni successivi alla morte della madre.

Isabella Blagden, however, did not limit her nursing care only to Lytton. In 1865 she helped Theodosia Trollope in her final illness and after her demise took care of her daughter Beatrice who stayed with her at Bellosguardo in the days following her mother's death.

Anche Elizabeth Barrett Browning, che tanto aveva lodato l’amica nel periodo in cui era stata infermiera di Lytton, fu assistita negli ultimi giorni di vita da Blagden. Eccezion fatta per i familiari, ella fu l’ultima persona che vide e parlò con la poetessa. Kate Field scrisse in un articolo dedicato a Barrett Browning: “on this final evening, an intimate female friend was admitted to her bedside and found her in good spirits, [...] willing to converse on all the old loved subjects”.33 L’ “intimate female friend” di cui parla Field, altri non è che Isa Blagden, la quale però, quella notte non riuscì a prendere sonno, nonostante avesse trovato l’amica in condizioni di salute migliori. Racconta Lilian Whiting che ella rimase l’intera notte alzata a scrivere delle lettere, finche all’alba un domestico non venne ad annunciarle la morte della signora di Casa Guidi.34

Also Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who so much praised her friend during the period when she was nurse to Lytton, was helped in her last days of life by Blagden. Except for the members of the household she was the last person who saw and spoke with the poetess. Kate Field wrote in an article dedicated to Barrett Browning 'on this final evening, an intimate family friend was admitted to her bedside and found her in good spirits, [ . . . ] willing to converse on all the old loved subjects'. The 'intimate female friend' of whom Field spoke, is none other than Isa Blagden, who, that night not being able to sleep, nevertheless had found her friend in better health. Lilian Whiting says that she stayed up the entire night writing letters, until at dawn a servant came to announce to her the death of the lady of Casa Guidi.

Blagden fu l’amica più vicina e sicuramente più utile a Robert Browning nei giorni che seguirono la scomparsa della moglie, durante il periodo che ella denominò “apocalyptic month.”35 Si addossò ogni cura materiale, condusse immediatamente il figlio dei Browning nella sua casa di Bellosguardo e dopo il funerale convinse il padre a passare le notti a villa Brichieri-Colombi,36 mentre gli ultimi doveri lo trattenevano a Firenze. Inoltre, come abbiamo visto, Blagden chiuse la sua dimora, depositò i suoi averi a villino Trollope e partì assieme a Robert Browning e il figlio per accompagnarli fino a Parigi.37

Blagden was the closest and certainly the most useful friend to Robert Browning in the days following the demise of his wife, during the period which she called the 'apocalyptic month'. She took care of every material need, immediately taking the Brownings' child to her house at Bellosguardo and after the funeral convincing the father to pass the night at Villa Brichieri-Colombi, while his last duties kept him in Florence. Then, as we have seen, Blagden closed her house, deposited her belongings at the Villino Trollope and left together with Robert Browning and his son to accompany them as far as Paris.

Sebbene una volta giunta a Firenze Isabella Blagden elesse la città toscana a sua residenza permanente, il viaggio rimase una parte fondamentale della sua vita. Infatti la scrittrice trascorse lunghi periodi lontana da Bellosguardo, recandosi sia in altre città italiane sia all’estero. Priva di legami familiari, poteva permettersi di viaggiare più liberamente di quanto normalmente fosse consentito alle donne, spesso “recluse” nello spazio privato della casa e della famiglia.

Although, having come to Florence, Isabella Blagden chose the Tuscan city as her permanent residence, travel remained a fundamental part of her life. In fact the writer spent long periods away from Bellosguardo, staying sometimes in other Italian cities or abroad. Having no family ties, she could permit herself to travel freely in a way not normally permitted to women, often 'recluses' in the private space of the house and of the family.

Tramite il viaggio, primo fra tutti quello che l’aveva portata dalla patria d’origine a Firenze, Blagden aveva avuto la possibilità di uscire dalla stabilità (il mondo “conosciuto” che viene lasciato alle spalle) per entrare nel regno dei cambiamenti, delle modificazioni, della frammentarietà.

Among the journeys, first among those being that which had brought her from her country of origin to Florence, Blagden had the possibility to come away from stability (the 'known' world which she had left behind) to enter into the realm of change, of modification, of fragmentation.

Ma per Blagden, donna inglese della middle-class, viaggiare significava solo parzialmente disfarsi della stabilità. Potrei definire gran parte dei suoi viaggi come “codificati”; per gli angloamericani residenti in città italiane era infatti un’abitudine radicata lasciare il luogo prescelto come fissa dimora per trascorrere lunghi periodi altrove. Isabella Blagden, come gran parte degli anglofiorentini, abbandonava la città toscana durante i mesi estivi, anche se, a causa delle sue precarie condizioni economiche, non poteva permettersi di lasciare la soffocante Firenze ogni anno.

But for Blagden, a middle-class English woman, to travel meant only partially to be removed from stability. One could define most of her journeys as 'codified'; for the Anglo-Americans residing in Italian cities it was in fact a rooted habit to leave the place chosen as the fixed abode to spend long periods elsewhere. Isabella Blagden, like many of the Anglo-Florentines, left the Tuscan city during the summer months, even if, because of her precarious economic condition, she could not afford to leave suffocating Florence every year.

Blagden spesso peccava di originalità anche per quanto riguarda le mete prescelte. L’itinerario seguito era costruito su una mappa dell’Italia molto selettiva. Sebbene virtualmente il territorio italiano potesse essere visitato per tutta la sua estensione, Blagden, come gran parte delle viaggiatrici straniere, si limitava a ricalcare un percorso classico che risaliva ai tempi del Grand Tour. Secondo un antico preconcetto vi erano solo alcune città che valeva la pena di visitare e poi eventualmente descrivere. Questo itinerario era, per quanto non fosse percepito come tale, una vera e propria restrizione culturale; di fatto lo spazio peninsulare era delimitato da tutta una serie di confini che dividevano spazi accessibili (le grandi città d’arte) e altri non accessibili (per esempio la costa adriatica).

Blagden was often culpable also as to the conventional goals she chose. The itinerary followed was constructed on a map of Italy that was very selective. Even if all the Italian territory could have been visited everywhere, Blagden, like the great part of the foreign travellers, limited her itinerary to the classic journey that arose at the time of the Grand Tour. According to an ancient preconception there were only some cities that were worthwhile visiting and then eventually describing. This itinerary was, though not perceived as such, a veritable cultural crippling; in fact the peninsula space was delimited by a series of confines which divided accessible spaces (the great cities of art) from those that were not accessible (for example the Adriatic coast).

Nel 1857, seguendo la “moda” angloamericana del periodo, si recò a Bagni di Lucca, dove sperava di trascorrere piacevolmente i mesi estivi. I Browning erano già confortevolmente alloggiati a “casa Betti”, quando Blagden arrivò accompagnata da Annette Bracken (che in quel periodo condivideva la villa Brichieri-Colombi con la scrittrice) e Robert Lytton. Essi presero alloggio in un albergo, il “Pelicano”, ma la vacanza si rivelò tutt’altro che piacevole, visto che Lytton ben presto si ammalò. Bagni di Lucca era un luogo di vacanza particolarmente gradito ai Browning, che vi avevano già trascorso le estati del 1849 e del 1853. Nella mente di Blagden il luogo divenne però associato con ricordi spiacevoli e Elizabeth Barrett era sicura che non vi avrebbe mai fatto ritorno.38Tuttavia, dieci anni dopo la scrittrice tornò sulle colline lucchesi e questa volta riuscì a apprezzarne la bellezza,39tanto che vi rimase diversi mesi, dal maggio all’ottobre del 1867.

In 1857, following the Anglo-American fashion of the period, she came to Bagni di Lucca, where she hoped to pass the summer months peaceably. The Brownings were already comfortably lodged at 'Casa Betti', when Blagden arrived accompanied by Annette Bracken (who at that period shared the villa Brichieri-Colombi with the writer) and Robert Lytton. She took lodging in a hotel, the 'Pelican', but the holdiday was far other than peaceable, seeing that Lytton soon took ill. Bagni di Lucca was a holiday place that particularly pleased the Brownings, who came there in the summers of 1849 and 1853. In Blagden's mind however the place became associated with unpleasing memories and Elizabeth Barrett was sure that she would never return. Nevertheless, ten years later the writer returned to the Luccan hills and this time succeeded in appreciating their beauty, so much that she remained for several months, from May to October in 1867.

Quella di Bagni di Lucca non fu l’unica vacanza trascorsa con i Browning. Nel settembre del 1859 fu, assieme a Kate Field, ospite di Villa Alberti, un edificio situato nella campagna senese, che i Browning avevano affittato per l’estate e in cui l’anno successivo i due coniugi tornarono a soggiornare. Anche Blagden prese in affitto una villa nelle vicinanze. Quell’estate, inoltre, erano nella campagna senese anche Landor e lo scultore William Wetmore Story con la famiglia. Barrett Browning stessa affermò: “this make a sort of colonization of the country here.”40Successivamente, Blagden tornò a trascorrere l’estate a Siena nel 1870, quando ormai Barrett Browning e Landor erano deceduti e Robert Browning era da lungo tempo in Inghilterra.

That at Bagni di Lucca was not the only holiday spent with the Brownings. In September 1859 she was, together with Kate Field, a guest at Villa Alberti, a building situated in the Sienese countryside, which the Brownings had rented for the summer and where the following year the married couple returned to stay. Even Blagden came to rent a villa in the vicinity. That summer, beside, in the Sienese countryside were also Landor and the sculptor William Wetmore Story and his family. Barrett Browning herself affirmed: 'this makes a sort of colonization of the country here'. Afterwards, Blagden returned to spend the summer in Siena in 1870, when Barrett Browning and Landor were already deceased and Robert Browning was for a long time in England.

Oltre ai luoghi come Bagni di Lucca e la campagna senese, che durante i mesi estivi venivano “colonizzati” dagli angloamericani, per Isa Blagden ebbero molta importanza le visite a Roma e Venezia, le due città italiane che, assieme a Firenze, i turisti stranieri ritenevano più degne di attenzioni. Il termine “visitare” non è del tutto esatto quando ci si riferisce a Roma, visto che Blagden, in due occasioni, risiedette nella città per vari mesi. Sebbene Firenze fosse il luogo di residenza prescelto da un gran numero di letterati, pochi artisti (tra i quali è però d’obbligo ricordare Hiriam Powers, un caro amico di Blagden) avevano deciso di stabilirsi definitivamente nel capoluogo toscano, preferendo Roma.

Apart from places like Bagni di Lucca and the Sienese countryside, which during the summer months came to be colonized by Anglo-Americans, for Isa Blagden visits to Rome and Venice were very important, the two Italian cities which, together with Florence, foreign tourists considered more worthy of attention. The term 'visit' is not at all exact in reference to Rome, given that Blagden on two occasions resided in the cities for various months. Although Florence was the chosen place of residence for a great number of writers, few artists (among whom we must, however, remember Hiram Powers, a dear friend of Blagden) had decided to establish themselves definitively in the Tuscan capital, preferring Rome.

La lista degli scultori e dei pittori che fecero della futura capitale il loro luogo di residenza permanente o comunque prolungato, è lunga e comprende tra gli altri John Gibson, William Wetmore Story, William Page e Harriet Hosmer, tutte persone con le quali Blagden era in contatto. Non di rado accadeva che coloro i quali avevano eletto Firenze a loro città adottiva, passassero alcuni mesi dell’anno, in particolar modo quelli invernali, a Roma. Blagden dunque, con la sua scelta di soggiornare per un periodo nella città preferita dagli artisti, non faceva altro che seguire una consuetudine radicata tra i cittadini angloamericani residenti a Firenze. Anche i Browning passarono più di un inverno nella “città eterna”. Per Blagden questa immersione nella Roma “of the artists”41fu utilissima da un punto di vista letterario, basta pensare al suo primo romanzo, Agnes Tremorne, la cui protagonista che dà il nome al libro, è una pittrice inglese che abita a Roma.

The list of sculptors and painters who made the future capital their place of permanent or at least prolonged residence, is long and includes among others John Gibson, William Wetmore Story, William Page and Harriet Hosmer, all persons with whom Blagden was in contact. Sometimes it happened that those who chose Florence as their adoptive city, would pass some months of the year, in particular those of the winter, at Rome. Blagden therefore, with her choise of staying for a period in the city preferred by artists, could not but follow the ingrained habit of the Anglo-Americans resident in Florence. Even the Brownings passed more than one winter in the 'Eternal City'. For Blagden this immersion in the Rome 'of the artists' was most useful from the literary point of view, suffice to think of her first novel, Agnes Tremorne, whose eponymous protagonist, is an English painter who lives in Rome.

Nel 1851 Isa abitò, assieme a Agassiz, in una casa situata al numero diciotto di via de’ Prefetti e tra gli anni 1854/55 scelse di stabilirsi al numero tredici di via Gregoriana. Questa strada, che si trova vicino a Trinità dei Monti, fu abitata da diversi nomi importanti della letteratura e dell’arte. Qui, infatti, come abbiamo visto, vennero ad abitare nel 1859 Charlotte Cushman, Harriet Hosmer e Emma Stebbins. In Via Gregoriana, Blagden colloca lo studio di pittore di Godfrey Wentworth, protagonista maschile di Agnes Tremorne. A Roma la scrittrice tornò anche in periodi successivi, ma non prese più case in affitto; vi si recava come ospite di qualche suo conoscente, come quando nel 1864 fu accolta da Charlotte Cushman.

In 1851 Isa lived, together with Agassiz, in a house at number 18 of the Via de' Prefetti and between the years 1854/55 chose to settle at number 13 in Via Gregoriana. This street, which is near Trinità dei Monti, was inhabited by diverse important persons in literature and art. Here, in fact, as we have seen, Charlotte Cushman, Harriet Hosmer and Emma Stebbins came to live in 1859. In Via Gregoriana, Blagden placed the studio of the painter of Godfrey Wentworth, the male protagonist of Agnes Tremorne. The writer returned to Rome in later periods, but never again rented a house; here she was a guest of those who knew her, as when in 1865 she was welcomed by Charlotte Cushman.

A Venezia Isabella Blagden probabilmente si recò quasi sicuramente prima del 1862, anno in cui uscì la sua seconda opera in prosa, The Woman I Loved and the Woman Who Loved me. La città è infatti uno dei luoghi in cui si sviluppa la storia, anche se il romanzo è principalmente ambientato in Inghilterra. E’ certo comunque che la scrittrice vi fece ritorno nel maggio del 1865, ospite di William Bracken, parente di quella Annette Bracken, con cui aveva condiviso villa Brichieri-Colombi. Era un periodo particolarmente triste per la scrittrice, poiché poco tempo prima era deceduta l’amica Theodosia Trollope, che aveva assistito negli ultimi giorni della sua malattia. Il viaggio comunque riuscì a distrarla e le offrì lo spunto per un articolo, intitolato A Holiday in Venice, che fu pubblicato sul Cornhill Magazine nell’ottobre di quello stesso anno.

Isabella Blagden probably went to Venice almost certainly before 1862, the year in which her second work in prose, The Woman I Loved and the Woman who Loved Me, was published. The city is in fact one of the places in which she develops the story, although the novel is mainly set in England. It is certain anyway that the writer returned there in May 1865, as guest of William Bracken, relative of that Annette Bracken, with whom she had shared Villa Brichieri-Colombi. It was a particularly sad time for the writer, since shortly before her friend Theodosia Trollope had died, whom she had nursed during the last days of her illness. The journey however succeeded in distracting her and gave the inspiration for an article, titled 'A Holiday in Venice', which was published in Cornhill Magazine, in October of that same year.

Isabella Blagden non si limitava a viaggiare in Italia, spesso si recava per lunghi periodi anche all’estero. Dal novembre del 1858 al marzo dell’anno successivo, soggiornò a Madrid. Nel luglio del 1871 la scrittrice visitò l’Austria, ma era l’Inghilterra il luogo in cui si recava tutte le volte che poteva permetterselo.42 Principalmente ella sceglieva Londra come meta, ma visitava anche altre zone, quasi sempre ospite di amici. Si recò in questo paese nel 1852 e successivamente a cavallo tra il 1854 e il 1855. Poi lasciò villa Brichieri-Colombi alla morte di Elizabeth Barrett Browning con l’intenzione di stabilirsi nell’isola britannica, ma dopo circa un anno fece ritorno a Bellosguardo. In Inghilterra tornò poi nell’estate del 1866 e in quella del 1868, quando visitò anche la Scozia. L’ultima visita di Blagden in questo paese risale all’estate del 1872. Nel gennaio dell’anno successivo ella morì.

Isabelle Blagden did not limit herself to travel in Italy, often going for long periods also abroad. From November 1858 to March of the following year, she stayed in Madrid. In July of 1871 the writer visited Austria, but England was the place which she visited as often as she could permit herself to do so. Principally she chose London as goal, but visited also other areas, almost always as a guest of friends. She went to that country in 1852 and later between 1854 and 1855. She left Villa Brichieri-Colombi at the death of Elizabeth Barrett Browning with the intention of settling in the British Isles, but after about a year returned to Bellosguardo. She returned to England in the summer of 1866 and in that of 1868 (when she also visited Scotland). Blagden's last visit to that country goes back to the summer of 1872. In January of the following year she died.